Qusayr ‘Amra.

The umayyad palace of the desert

(Part I)

By Antonio Almagro Gorbea

The originality of the architecture of this monument, including its poetic frame of desert solitude, makes it a major milestone in the history of Arab art. Frescoes in its interior, of a high iconographic and artistic meaning, have remained almost invisible because of neglect over the centuries. Today, the ensemble can be admired after the great restoration task undertaken in the nineteen-seventies thanks to the collaboration between the governments of Jordan and Spain, that sent an archaeologic team to the site.

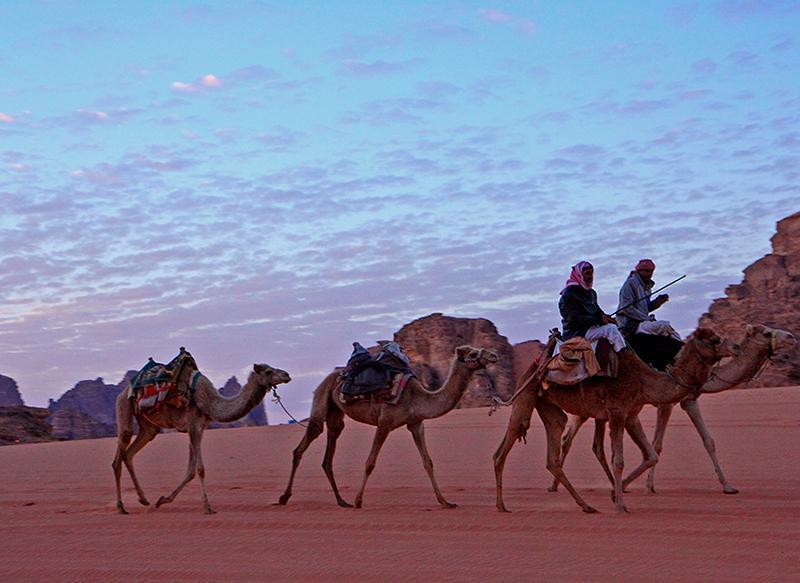

This monument, a real gem of Islamic art, declared World Heritage, comprises a series of small constructions aimed to be a place of retreat and solace for any chiefs of the Umayyad family. What surprises us, more than the singularity of its architectural solutions, is its emplacement in the middle of the desert, and the rich pictorial decoration which covers its walls and interior vaults. The desert with its vast immensity is a breath-taking reality. It can easily make us react in a similar way as the sea does on contemplation, because of its unlimited horizons, the feeling of solitude and that grandeur that is always present in natural phenomena. Thus, it is not surprising that the singularities we can find in the desert amaze us even more due to the contrasts that it generates amid this astonishing natural frame.

Many are the deserts that apparently are full of fauna and vegetation, at first sight almost non-existent, but sometimes of a surprising richness and variety. And although the harshness of these places may lead us to ponder how man can be adapted to their rigours, we are sometimes bewildered by human actions whose meaning and transcendence are not always easy to value.

Wadi Rum, the Jordanian desert.

Therefore, Qusayr ‘Amra is for all these reasons a singular monument. It is, above all, an oasis of architecture in the midst of naked nature, apparently reduced to its minimum expression; a construction in the middle of the desert aimed at the leisure of people with scarcely any architectural tradition, who created in the middle of an enlarged wilderness a microcosm full of refinement and symbolism whose interpretation raises countless conundrums and suggestions.

Today, the place has suffered important transformations due to the road which runs scarcely one hundred and fifty metres away from the main building, and to the auxiliary constructions that tourism has imposed, which have been placed there with scant fortune. Yet, we can still be enthralled by the almost infinite vision of the desert that expands towards the depression of Azraq, or by the slight manifestations of life that indicate the solitary trees that border the dry riverbed of Wadi Butum.

Despite the urban development and colonisation in our days that have been penetrating the desert, as we approach the eastern part of this city we will notice the disappearance of life and vegetation as terrain slopes down, in an almost negligible way, from the Jordan plateau towards the interior depressions of the Syrian-Arabian desert. Dry riverbeds draw an increasingly flat orography that ends by melding in something of a lowland shaped by soft hills, which gives the landscape an ever-changing horizon.

Wadi Butum is almost the only area with some vegetation in this desolate landscape. What was it that prompted an Umayyad prince, perhaps Suleyman, the son of the great caliph Abd al-Malik in times of his brother Walid I’s caliphate, to build in this lonely place such a singular building? It is hard to give an adequate answer to this question without considering the historical situation in which it was built. Fewer than 80 years had passed since Arabs −who arose from that huge desert which expands to the south and east of Amra, moved by the faith of Islam−, had faced the great rival empires: the Byzantine and Sassanid, destroying both and totally absorbing the second of them.

Qusayr ‘Amra is crossed by a caravan route which, from the Hejaz in Arabia and the Gulf of Aqaba, headed toward Iraq and Kuwait along the edge of the Jordan plateau, crossing the oasis of Azraq. This itinerary is the same that the current road follows, although its heavy traffic has radically transformed the original atmosphere of the place.

With the Umayyad dynasty, the first of the Arab world, Islam’s expansion reached Africa and Asia, and ‘Amra witnessed the arrival of the Arabs to the Iberian Peninsula and the Visigoth King Roderick’s defeat, while on the other end of the world the Arabs reached the river Indus. The new dynasty, which had immediately adapted the monarchical forms to the figure of the caliph or prince of believers, soon faced ideological and image problems. On the one hand, the lack of tradition of political and religious power within the Arab peoples, extended to all their tribes apart from conquered people, meant the absence of symbols and the prerogatives they carry, among them an architecture as a vector of the expression of power. And on the other hand, the required dominion over the peoples that already had those traditions, in one way or another, demanded to preserve or create new ways to visualize and recognize through them the new political reality.

Hence, Qusayr ‘Amra must be understood in the context of the wish of the new dynasty to assimilate and to present itself, mostly to its followers and supporters, as the face of their new subjects of different religion and culture, that they were the new rulers in the territories that they now controlled. It represents the assimilation of customs that before were at odds with Arab culture, like the Greek-Roman bath, with iconographic elements of a high symbolism taken from the defeated cultures and peoples. Qusayr ‘Amra is without doubt a splendid example of the nascent Islamic art.

Antonio Almagro Gorbea

School of Arab Studies of Granada