Qusayr ‘Amra.

The umayyad palace of the desert

(Part II)

By Antonio Almagro Gorbea

The originality of the architecture of this monument, including its poetic frame of desert solitude, makes it a major milestone in the history of Arab art. Frescoes in its interior, of a high iconographic and artistic meaning, have remained almost invisible because of neglect over the centuries. Today, the ensemble can be admired after the great restoration task jointly undertaken by the governments of Jordan and Spain, that sent to the site an archaeologic team lead by expert scientists from the School of Arab Studies of Granada.

‘Amra was not a singular case in the times of its construction, although today it is, because of its almost miraculous conservation. We have examples of similar buildings in its surroundings which have unfortunately reached us in a more ruined state. Among them the hammam al-Sarah stands out, probably built later, given that some architectural details more evolved were used. But nothing has remained from its decoration, which we can guess was similar or even richer than that of Amra. Its location, in a place closer to populated areas, made for a more precarious conservation, and there is even proof of the continual plundering of building materials until recent times. The solitude and remoteness of Amra rid itself of this trance that only affects the most noble of materials: the marble boards in floorings and plinths, as well as the mosaics which covered some of their vaults, and some other decorative or functional element of the bath.

The ensemble is composed of a main building and others scattered in a radius of some 600 metres around it. Only the first one has reached us in a good state of conservation, while the rest are in ruins. There is a well with its waterwheel located towards the east that might have helped to water a reduced part of the garden that would expand between the main construction with an uncertain limit. Unos 550 metros al oeste, y en una ladera de la margen izquierda de wadi, están las ruinas de un edificio aún no excavado que quizás nunca se llegó a concluir. It follows along with other types of contemporary castle-residences, although this one can be placed among the smaller ones. It might have been used as the main residence or for the prince’s retinue.

The main building, today preserved, has a well with its waterwheel by its side, and also an elevated depot to supply the bath and the reception room with water. The well was dug up to a depth of 26 metres through the rocky base of thewadito reach the water table. The scope of this work clearly shows the importance of this setting in the middle of the desert.

The most interesting of what we can see today in Qusayr ‘Amra is the building which integrates the reception room and the bath. While this shows a very varied profile in its exterior, it still shows its internal feature. The two main functions, reception room and bath, are evidenced; the first one by its rotund volume, with a greater height, while the rest of the rooms of the bath provide volumes of varied and juxtaposed shapes. The reception room, in the floor plan, is a square divided into three naves by means of two great diaphragm arches disposed in a direction parallel to the axis of the hall. The three naves are covered with barrel vaults pierced by ceramic pipes which allowed a discrete cooling. The door opens in the axis of the room, in its north side, while in the opposite side there is a small room or niche that might have been a throne or presidential room. This small room was flanked by two more rooms, with access though small doors located in the central hall, whose purpose might have been as bedrooms or a rest area. In a corner of the reception room there was a sink which was provided with a channel for water supply and drainage that ensured the permanence of running water. Floors and plinths were made of marble, while walls and vaults were covered with exuberant pictorial decorations which, despite being partially deteriorated, has reached our days in quite a complete state.

This decoration is without doubt the most outstanding element of Qusayr ‘Amra. First of all, it is surprising to find such a wide repertoire of figurative representation in an Islamic building. It clearly contradicts the assertion −so topical− of the Islamic prohibition against figurative representation. In this respect, it should be convenient to stress that, first, Amra is an example of the first art of Islam, when its most genuine features were yet to be defined. Moreover, there is a no restrictive prohibition in the Koran regarding these types of representations, which rather obey later interpretations and the tradition, fully imbued in Semitic culture. It rather looks to abstraction and avoids the realism of representations, which has conditioned mainly the practice of fleeing from artistic representation. But such practice has not been absolute nor in all times nor in all places.

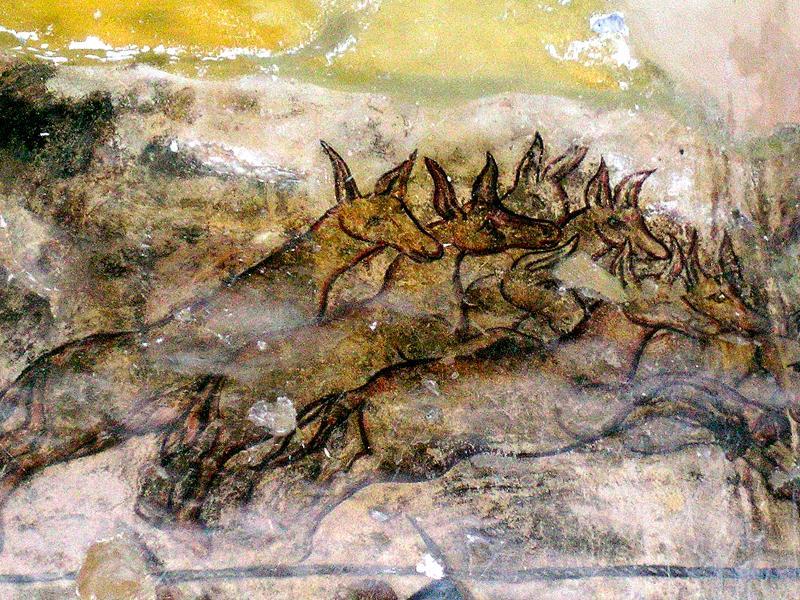

The bath is composed of three rooms whose entrance has a double-bended shape. Access to the first of them, which might have been a small wardrobe to leave the clothes before getting into the wet room, was through an entrance located in the eastern side of the reception room. It has a small bench, and its barrel vault is decorated with diverse figures and motifs that are simply ornamental. They include some circus-style groups of musicians, with a bear and figures of dancers, some of which are also animals, the three stages of life, gazelles, cranes, onagers, etc.

Nonetheless, the paintings of Qusayr ‘Amra comprise a unique case that has been analysed at length by specialists and scholars. Some of them have considered it an example of Byzantine art, to whose style and technique it owes almost everything. Yet, as we have pointed out, its realization is in line with the absolute new motivations and requirements that turned this ensemble into a fundamental keystone in Islamic art.

Among the numerous scenes that decorate the main hall, we will highlight the set that covers the arches and the vault in the central nave. They all represent welcoming figures, featuring people and scenes of courtly life, some of them being difficult to interpret. These images lead us to the bottom of the apse, or small room of the throne, where appears the image of the prince or caliph sitting enthroned and surrounded by symbolic figures for the sovereign’s power and glory.

The central nave to the right has what is certainly the richest and most interesting scenes. On its south side there is a feminine figure, lying down on a couch, who might be interpreted to be the wife or the favourite, accompanied by the prince, who appears in the background, together with several figures which complete the scene.

The large western panel gathers diverse compositions, among which the group of kings defeated by Islam, or simply world rulers, bearing their name upon their images: Caesar Byzantine emperor; Roderick, Visigoth king; Khosrow, Sassanid emperor; Negus, king of Abyssinia; the names of the last two ones have not survived, but it is possible to suppose they may be the emperor of China and a Hindu king or one from Turkestan. Their attitude seems to be either of submission or assigning authority to the prince who appears as the main character in almost every scene in this room. Next, a feminine figure getting out of the bath appears nearly naked in a sports or gym scene. The feminine figure could be the same wife or favourite who also appears surrounded by diverse people who observe the scene within an architectural framework. The scenes of wrestling, like the one aforementioned, could have taken place as part of the courtly activities or scenes, or just as an entertainment whose parallelism can be found in the classic and Byzantine world. SThere is a wide representation of the hunting of wild donkeys, which continues in the right nave, in whose walls appears the prince, first spearing, and later on skinning these animals. The vault in this room has a very interesting series of activities and crafts related to the construction, probably connected to the very same building.

The scenes in this room have, in general, both a symbolic feeling and of the representation of the court or activities related to the life of the prince. They contrast, perhaps, with those depicted in the rooms of the bath, which are of a more intimate character.

The next room is the first room of the bath in a proper sense. It was equipped with a hypocaust or lower chamber to warm it, which extended through the walls by means of ceramic tubes covered by marble panels. Much of the flooring, like the elements of the lateral chambers, have been rooted out, but its sophisticated disposition can be easily understood. Most of the small basalt pillars that supported the room’s flooring, giving shape to the hypocaust, are still preserved. In the opposite side to the entrance there is a small niche that hosted a bathtub. The groin vault that covers it is decorated with vegetal motifs, while in the tympanums of the walls appear intimate bathing scenes with nude women and children.

The last hall, which was the main hot room, was covered by a vaulted ceiling with a hemispheric dome decorated with paintings, supported by spandrels once covered by mosaics. The lower part of the walls was coated with ceramic tubes and marble panels as in the previous room.

In the dome there is a representation of the zodiac, forming a celestial vault. This subject refers, without doubt, to the presence of the prince in this room, around whom the universe represented in the dome revolves..

This is a very recurrent subject since ancient times, and even in other Islamic monuments, being linked to the symbolism of power, the sovereign being foreseen as the centre of a universe that revolves around him. The room has two bathtubs located in two circular shaped niches, and it has also a hypocaust as in the following room.

Next to this room, but with access from the exterior, there was the large tank for the water supply of the bath, made of masonry. It was placed on the fireplace, which heated it and the whole bath thanks to the system of dampers that moved hot water through the hypocaust and the cavities which covered the walls, getting to the exterior through the holes located in the vaults. The whole hydraulic system was supplied with the water from the elevated tanks placed by the well, outside the building. The fireplace was inside a room where firewood was also stored.

By means of this brief description, we have been able to see how refined the conception of this small architectonic ensemble was, incorporating the use of the steam bath into Muslim culture, as a response to the religious imperative through a practice totally alien to Arab culture. Despite the large thermal baths of classical ancient times, cool water pools were also included to bathe −in domestic baths and through the evolution experienced in Byzantine times− that were generally a type of bath like those of Qusayr ‘Amra, that were adopted by Arabs, including in public baths.

The use of the hammam was widely used all over the Islamic territories in medieval times, becoming one of the most distinctive elements of the of the cities of al-Andalus.

In the image, the historic Bañuelo, in Granada, dating from the Nasrid period.

It is evident that the construction of a bath in such an isolated palace as this desert did not correspond to any question of ritual, but rather it should have been, above all, a way to incorporate into daily life pleasant customs other civilizations offered to the new princes, allowing them, in this way, to show off their new economic and political status. Qusayr ‘Amra was not a public palace aimed at big audiences, but as its very paintings tell us, a place of retreat to enjoy traditional activities such as the hunting of wild animals in the desert atmosphere, from where the Umayyads came from.To these, they added other refined activities like the steam bath that they acquired through their newly cosmopolitan condition. However, influential figures never stopped arriving to these palaces whom the Umayyads wanted to honour, or just make them understand the new status that the ruling family members had reached. The building, despite being away from the urban nucleus, is located by a very important caravan route, which would not make it pass unnoticed.

Qusayr ‘Amra is thus a good paradigmatic example of the birth of a new art in the service of new necessities but that at the same time has benefited from the techniques and motifs of the cultures that preceded it.

Antonio Almagro Gorbea

School of Arab Studies of Granada