Glorious tiles

Appearing in parks, squares, bars and homes, tiles—azulejos– have for centuries accompanied the decoration in many regions of the Mediterranean. Today, they are as alive as ever; in fact, their designs are new and innovative.

They are beautiful and burst with colour. Tiles played a fundamental role in the aesthetic of al-Andalus. Inherited from this culture, they are incorporated today in new decorative models. He are, described, their latest keys.

It struck me rather suddenly one day in Seville. Tiles were starting to appear wherever I looked. So far, they only represented a gift for sight. They were there, decorative, full of colour; that was all. Passing a gently splashing Andalusian fountain, I realized it was decorated both inside and out with strikingly beautiful tiles inspired by the Alhambra. I looked around and more and more tiles kept on appearing, framing horseshoe-arched windows, on the lobby walls of a building across the street, covering floors, walls and ceilings, even along the reception desk of the hotel in which I was staying. From then on, they have been a sweet obsession. I started to notice them everywhere in both Spain and Portugal.

Tiles are in cafes, bars and restaurants, where they often portray scenes from daily life like the chores of the farm and the kitchen, hunting and fishing, folk dances, flowers, cows and rabbits, and more. Tile “paintings” are also everywhere—mostly in historical moments with great, bucolic idealism. They are in churches and ancient monuments, and even in the humblest homes. There is an Arab proverb dating back to al-Andalus that says, “The poor man lives in a house without tiles.”

Tiles decorating a balustrade in Plaza de España, in Seville.

Also, in Spain as in Portugal, the world of azulejos—tiles— is as vast as it is varied; so beautiful and so colorful that it presents us unfathomable riches.

The word azulejo comes from the colloquial Arabic al-zulaij, meaning “faience or ornamental tile”. Decorative tiles were first made in Syria, in the valleys of rivers Euphrates and Tigris, and in Persia, where the first decorative and luster-painted tiles were produced in the Persian city of Kashan since at least the ninth century. Used primarily to decorate the walls of mosques, by the 13th and 14th centuries Kashan tiles were known for their excellent workmanship and intricate design. They were employed primarily in the decoration of the walls of mosques. They were not only square or rectangular but were also made in interlocking polygons whose individual pieces were part of a grander design – foreshadowing the artistic excellence exemplified at the Alhambra.

Tile art spread and moved west, and Spanish tile eventually became far superior to its eastern predecessors. One reason, according to some experts, may have been the flood of artisans into Muslim Spain, or al-Andalus, as a result of the unrest caused by Genghis Khan, and because al-Andalus was a cultural crossroads where crafts that had come from the East via Egypt met and were enriched by the late Roman and Visigoth as well as other Mediterranean decorative traditions.

Why were tiles so popular? First because they replaced marble of different colors, which was expensive and very hard to come by. Besides, artisans had perfected techniques for making tiles in a great variety of colors, offering an easier and cheaper way to beautify a house or mosque or palace. The raw materials, too, were widely and readily available.

Leaving aside the beauty of tiles’ design, there were other, eminently practical reasons: Good tiles afford excellent protection for walls or floors, they last forever, and they are easy to clean. In al-Andalus, they were essential to the widespread private and public toilet and bathing facilities.

Façade of a house in Lisbon

Fierce rivalry among the great cities of al-Andalus like Seville, Granada and Córdoba spurred the wealthy and their artisans to new heights. The ornate tile designs of intertwined floral, foliate and geometric figures –known as arabesque– became ever more complex and sophisticated, perhaps reaching their ultimate expression in the beauty of Nasrid Art.

Why were tiles originally made? When the Mesopotamians first used glazes, it was a construction material to make mud walls water-resistant rather than as decoration. But glaze also allowed the introduction of color, and surfaces of decorated arabesque panels and painstakingly drawn bands of complicated calligraphy became an indispensable element of Islamic architecture.

How were they made? Tiles were often made to fit a specific wall or floor. First, they were designed in place and then sent to a workshop, the clay slabs usually covered by a fine layer of liquid clay called slip, on which drawings were made.

The methods of making tiles were basically similar in Mesopotamia and al-Andalus. Refinements came in later stages, when special colors and a metallic sheen were produced. The competition in tile production in al-Andalus was so intense that Moorish craftsmen, in order to obtain maximum brilliance and transparency effects, had lead shipped from Venice and tin from England, since these were considered the very best.

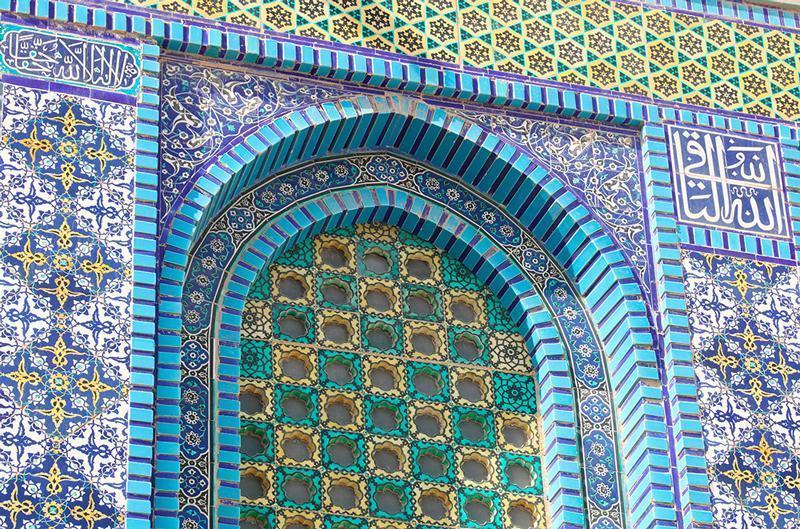

Decoration in the exterior wall of the mosque of al-Aqsa. Jerusalem.

The following description of how tiles were made corresponds to the methods traditionally used by Spanish Muslims. These methods have hardly varied, leaving aside industrial mass production. The slabs themselves were made from high-quality white clay, ground to a fine powder, sieved, mixed with water and then trodden like grapes until properly wedged. The slabs themselves were made from high-quality white clay, ground to a fine powder, sieved, mixed with water and then trodden like grapes until properly wedged. To remove excess moisture, the clay was clapped onto an absorbent plaster wall. When partially dry, it was molded in wooden boxes and cut into rectangular sizes, then fired in what are still known as Moorish, or Arab, kilns, which, by the way, can be seen still nowadays. These brick kilns still exist in the Valencia region, in the ancient ceramic centres of Manises and Paterna, as well as in Andalusia. They are not, of course, the exact same ones used in Islamic times, since the bricks eventually crack with repeated use and the structure must be rebuilt. But it is rebuilt in the same manner as before, and often on the same site.

The kilns consist of a larger lower chamber called the caldera, and an upper chamber called the “laboratorio”. They are connected by holes in the floor of the upper chamber that allow heat to pass. The clay slabs were placed on a platform at the rear of the lower chamber. A wood fire and, in the olive-growing regions in the south, leftover olive skins and pits (orujo), provided the intense heat required to fire the clay. The resulting absorbent, porous slab was called biscuit (bizcocho) and was now ready to be painted. Occasionally the painting of the tiles is done with the tip of a mule’s tail, and women I spoke to said there is no better brush. Copper, manganese, platinum and cobalt oxides and alkaline silicates are mixed with water to produce the paint itself. Next, the tiles were dipped in glazing fluid containing lead and tin oxides -originally a lead-sulfite paste- dissolved in water. The tiles were then fired again in the laboratorio, or upper chamber, where the temperature was lower, and no flames could reach them. During this process, the glaze and pigment fused into hard glass, with a high degree of brilliance and smoothness.

Designs in the early days were all arabesque – floral and geometric patterns. When animals were drawn, it was always in a highly stylized manner in deference to Islamic tradition. Later, under Christian influence, human figures as well as animals were drawn realistically.

Tile representing a genre scene in Portugal

Many of the older tile-painting methods, including cuerda seca (or “dry line”) are still in use today. But because traditional tile-making is labor-intensive and therefore costly, it is being replaced to a large extent by factory production. However, most serious tile-making companies maintain a handcrafted line of tiles to supply connoisseurs, and though a factory may acquire two or three gas- or electrically fired kilns, it often retains at least one fired by wood. As Mark Verderi adds on Mensaque, Seville’s famous workshop tile makers, “it is partly the black smoke of the wood-fired kiln that reacts with the chemicals on the tile and give them a certain color and their lovely personality.”

Mensaque, which exports all over the world, has encountered a small problem with its Japanese customers -perhaps an indicator of how the rest of the world is going. As Verderi explains, “the Japanese, who are extremely interested in everything that is European, old and famous, have a problem with our hand-made tiles. They say they are not all exactly the same, that our tiles are uneven. They want them perfect, completely perfect. And we are trying to educate them to the fact that this unevenness is precisely what is so lovely about the good tiles. They are the same basically, but not completely identical.”

Puerta del Vino. Alhambra. It shows a beautiful sample of tiles in its alfiz.

Granada’s Alhambra came to be the symbol of perfection in the use of tiles. Be it simple or intricate, its patterns are endlessly copied or used for inspiration and study, and they are still the most popular of all. Lately there has been a resurgence in demand for these classical patterns, whether hand-made or churned out of a factory.

In Portugal, the earliest tiles were imported from Seville and the Valencia region of Spain. At the end of the 15th century, tiles made by Muslims were used to good effect in the cathedral of Coimbra and in the Royal Palace of Sintra, where they can still be seen. Production of tiles in Portugal dates to the second half of the 16th century. The Portuguese style soon took a different tack from that of Spain. Large, tiled panels began to be used both inside and outside buildings and palaces. The scenes generally illustrated religious history or depicted life in the countryside. The techniques were undoubtedly of Muslim origin, but their use developed into something quite different.

In Portugal, the murals’ long tradition is as strong as ever. Lisbon’s streets have huge, modern tile mosaics, and the walls of the Lisbon subway stations are covered with patterns of tiles done by some of the country’s foremost artists.

Although Spanish and Portuguese tiles are exported by the millions to embellish the walls of Arab countries, to cover bathrooms in America or swimming pools in Singapore, the magic world of tiles from both countries will never be matched.

Frieze decoration on the façade of a house in Lisbon

Tor Eigeland

Photojournalist and writer

Abridged from “The Tiles of Iberia”

published in AramcoWordmagazine,

March-April 1992