Saints and romerías in the Maghreb and Andalusia

Neither the soul, nor popular religiosity understand particular religions and borders. They have more to do with the paths that Ortega y Gasset called “Intrahistory” and those of life itself..

When I first entered the Qayrawani’s medina of Fez some forty years ago, I met an entourage playing in a band with trumpets and drums, and chants that surrounded a boy upon a horse with his grandfather. The boy was taken to the sanctuary of Moulay Idriss to get him circumcised. I followed that procession, and so I met with my first Moroccan saint, buried in a tomb covered by a velvet embroidered tapestry in the middle of his hermitage, in one of whose doors sprouted a fountain from which many pilgrims drank. Some of them were black, and that showed how far their devotion stretched.

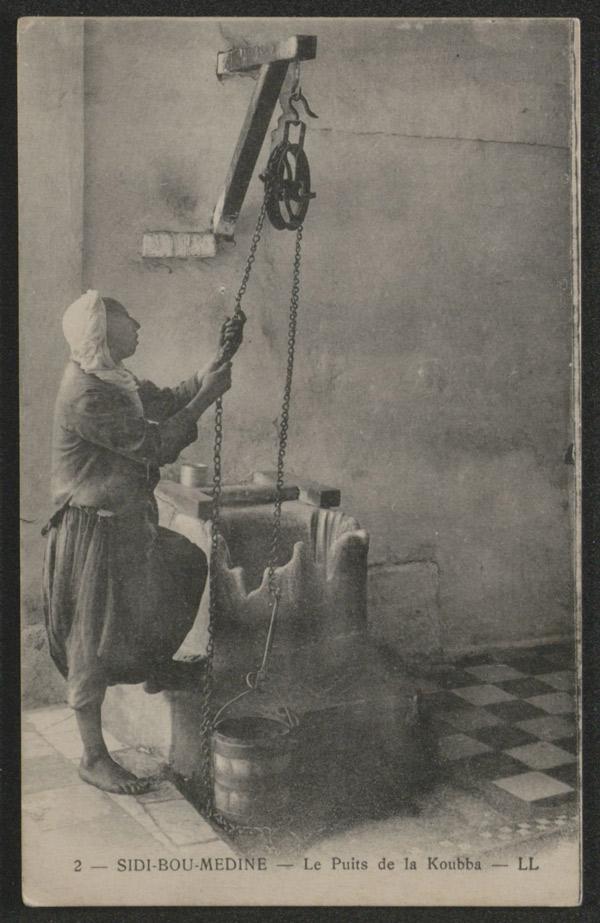

I met the second one near the Algerian city of Tlemcen, and he was named Sidi Boumediene the Sevillian, it was through him that I started to be interested in the subject. It was not that difficult, for the great Arabist Miguel Asín Palacios had treated him, both in the translation of the book Lives of the Andalusian Saintsby Ibn Arabi, and in dealing with the spirituality both of the disciples of the Tunisian Abu Hassan el Chadili ̶ who was likewise the disciple of Boumediene ̶ and of the Carmelites. There was then a subtle thread of connection, but a connection anyway, which inked the African saints with San Juan de la Cruz.

But the spiritual or theological height that those people reached in their lives is one thing, and quite another is the multitudinous devotion that arose afterwards, that occasionally, hardly resembled each other. There is no reflective relationship in Mediterranean Islam between Boumediene’s thought and those who celebrate it, just as it does not exist either between Saint Benedict ̶ the founder of European monasticism and hence the patron of Europe for Catholics ̶ and the pilgrimage of the Andévalo region (Huelva), full of dances and folkloric elements. People that celebrate it little know about the mystical or theological ideas; they are simply important because they became the local and popular saints of the cities, and they represent a community.

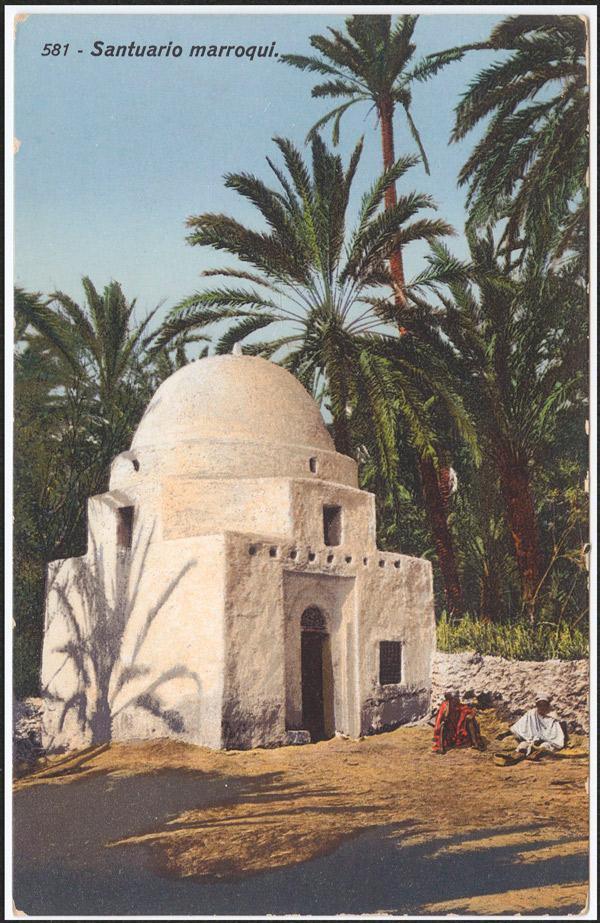

Old postcards Old postcards depicting the Sidi Boumediene complex in Argelia (left). Right, a Moroccan sanctuary or marabout.

All along the southern Mediterranean shore, as well as in the Andalusian countryside, shrines or small hermitages devoted to miracle-working saints generate great devotion among the peoples of the regions.

Following this path, I discovered that, together with the many Muslim saints, their brotherhoods and, in a certain way, their attitudes, ceremonies and events, were not so different from those in Andalusian popular religiosity. In much the same way it has happened in the history of Andalusia, the religious brotherhoods from the Maghreb gathered people from very different environments and social positions, and they developed diverse rites: among these entities there are the aristocratic ones and the popular ones, with practices silent and ebulliently loud, even rowdy; others are similar to the old ones known in Spain as “de sangre” (of blood), and there were others where chants and drums prevailed, like the gnawas(with their Sub Saharan rhythms) or the aisawas that could be compared to the “rocieras” (related to the pilgrimage of El Rocío, in the Spanish province of Huelva) when its sound was heard in the Plaza de España in Tetouan.

One of the most widespread of the brotherhoods in the Arab world is the Kadiria, whose patron is Abdul Qadir al-Jilani. Their brotherhood homes are known as zawiyas or according to the Gallicism, zagouias (although in Spanish there are some terms as azulla or zauya) and they are located mostly in cities from the Maghreb. In the 1920s, professor Michaux-Bellaire wrote about the devotion of many women to this saint, and they come before him every Friday to present votive offerings, lighting candles and burning incense: “It is to Moulay Abdul Qadir to whom they express their sorrows by telling him their little stories, those which cannot be told to anybody else; to complain about their husbands or other women: they entrust their miseries to him, their aspirations, hatreds, and sometimes, their most intimate affections”.

The Romería of El Zalabí in Exfiliana (Valle del Zalabí, Granada). Ayuntamiento del Valle del Zalabí ©J.M. Romacho

Like most of the Andalusian romerías, this shares the common theme of the worship of the Virgin Mary. Traditionally, these romerías have their origins in the miraculous finding of an image of the Virgin in the countryside, along with a sign from her that asks for the construction of a shrine in her honour, to which every year a celebratory romería can be undertaken.

The scene is reminiscent of what happens in any of our cities (also in that day of the week), which anyone may imagine, particularly those of Jesus of Nazareth in his many advocations, and even the nicknames addressed to the members of the brotherhood and his worshippers. Actually, on either side, and independent of theology ̶ without transgressing it though ̶ those figures have adopted the profile of the paterfamilias’, the head of a spiritual and sentimental lineage.

In some cases, such as that of Abdul Qadir, that devotion transcends national borders and races. However, in other cases, and in most of them, it is about saints whose figure shines in a local or regional environment. They are something similar to what we ourselves know as patrons.

Every community, even though it may worship others, has its own cult, in the same way many professions have, and the patron saints have given rise to big or small rites, together with gastronomic specialities linked to their names. Tetouan‘s patron is Sidi Saidi, who was born in Ceuta and lived in the 13th century and has his hermitage by the gate that bears his name: Bab Saida. Larache has a very popular miracle-working saint, Moulay Bousselham, who shares worship with the good woman who helped him, Leilah Maimunah. Both are worshipped in a pilgrimage that takes place every year in a spot known as the Blue Lagoon.

A view of the Mosque Qarawiyyin, Fez ©Xurxo Lobato

Interior of Moulay Idriss’ mausoleum, In Fez (Morocco) ©Xurxo Lobato

The one in Fez is Moulay Idriss, already mentioned, and that of Marrakesh is Sidi Bel Abbes, also the protector of farmers, the same role that Saint Isidro has for us in Spain. He was a malamatimonk (type of Sufi), with a vow of poverty like the early Franciscans. Ibn Rusd, who had to examine him dogmatically, concluded that his poverty aimed at generosity. Since Sidi Bel Abbes arrived in Tetouan in the 13th century, he was also well regarded among the fritter-makers who, day after day, offer their first fritters to kids and poor people. These fritters were named abbasiya in his honour.

In Ksar el-Kebir, Sidi Ali-Boughaleb, another mystic who came there from al-Andalus, is the one who brings together his devotees. He is also a miracle-worker, and highlanders visit his shrine on market days, bringing him offerings.

Abu Mohamed Sali, founder also of a brotherhood, is the patron saint of Safi, just as Abd er-Rahman al-Talabi is in Algiers. Moroccan cavalry is under Sidi Mohamed Cherqui’s protection, in the same way that in Spain has the patronage of Santiago.

In Salé, which was virtually a republic of Al-Andalus up to the 700s, there were two saints who shared the same sentiments: the first is Sidi ben Asir, born in the city of Jimena de la Frontera in the province of Cadiz and friend of Ibn Abad from Ronda, whose worship, in serious and stringent rites, could be compared with that of Jesús del Gran Poder of Seville. The second one, Sidi Abdala Ibn Hasun, is celebrated in a much more festive way, in the procession with candles that takes place every year for the “Feast of the Mawlid”, that of the birthday of Muhammad.

At the edge of the medina of the limits of Tunis, between the wall of the Andalusian neighbourhood and the lagoon, we find a singular example: the revered tomb of Abd Allah al-Tarjuman, known in Spain as Anselm Turmeda, a monk and prolific writer who embraced Islam and yet kept good relations with the Catholic church, without his works ever being condemned.

The headquarters of these associations are usually located next to the saint’s shrine or zawiya, and they host schools or madrasas, a hostel, sometimes a hospital. In many of them, the Moriscos who were expelled from Spain in the 17th century were able to find accommodation.

But no doubt, above all there is Moulay Abdessalam ibn Mashish, whose shrine is on the top of mount Alam, in the Kabyle of Beni Arouss, halfway between Tetouan and Chaouen.

We have already mentioned him at the beginning as one of the greatest masters of mysticism, but his devotion among the people and the importance of this figure is also linked to history, and, particularly, to a battle.

The site, similar in appearance to the Peña de Arias Montano, in the mountain range of Huelva, is overwhelming in its beauty; it is actually a musalla, or open space for prayer, where only a small booth made of stone without plaster protrudes, and in the background, two stones, almost attached, that people pass between them so as to obtain the baraka, or blessing. The whole ground of the plain that tops the mount is covered with sheets of cork produced by the neighbouring cork trees and, hardly noticeable, the whitewashed wall of the hermitage, blackened by the smoke of the candles that the many devotees leave burning.

The “other Lepanto” was how Fernand Braudel named the battle of the Three Kings in his work The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the times of Philip II, and it is true in a certain way, for it meant the end of the Portuguese expansion in Morocco. The battle was fought on the banks of river Lupus, near Ksar el-Kebir, where the king of Portugal Don Sebastián lost his life, as did the sultan and the candidate to the throne, allied with the Portuguese.

People from Granada played a very important role in the battle. They arrived after the break of the capitulations, bringing military experience that they had gained in their civil wars against Castilians and the Raisun family (the famous Raisuni from the beginning of the 20th century), with their plot of land in Beni Arouss.

Roman ruins of Volubilis (Morocco) and the city of Moulay Idriss in the background.

The Raisunis are Idrisids ̶ descendants of Moulay Idriss and the village that takes its name from him, near the Roman ruins of Volubilis ̶ who were allied with the Umayyads during the Caliphate of Cordoba, and under their rule they colonized the northern Maghreb. We should assume that this politics continued somehow, for at the end of the 15th century they became members of the Andalusi families of Sidi Al-Mandri and Moulay Ali ibn Raschid, founders of the cities of Tetouan and Chaouen, respectively. The mortal remains of Al-Mandri’s wife, the sultana Sayyida al-Horra, are in the house-palace of the Raisunis in Chaouen.

The victory is still celebrated in the ceremony of the “Megillah of the Kings” by the Sephardic Jews, who were not well considered by the Portuguese king. The victory was attributed to the protection of Moulay Abdessalam, and his sanctuary reached the highest regard ever since, both by the royal side and by ordinary folk. In this way, it was often the untouchable refuge for those who were persecuted by the sultan or the powerful families. As the fame of Moulay Abdessalam grew throughout the country, so did the appreciation for the Morisco families.

Thanks to this historic situation, the dynasties from the Maghreb held onto more power and stability that today’s Alaouites, who came from Ouazzane, in the banks of river Loukkos, in the opposite shore of Ksar el-Kebir.

From the 18th century on, these monarchs, like what happened in Spain, made political use of the brotherhoods that were divided in their religious beliefs to expand their own ideas and influence. In Spain, it is worth mentioning that it was then when the Enlightenment’s administration furthered the canonisation of San Isidro Labrador (the Farmer), in hope that, after waiting for centuries for the Vatican’s decision, the purpose of this canonisation was to expand the love of agriculture by means of the saint’s devotion and “restrain” that of the “Divina Pastora” promoted by the friars, whose mentality inclined more toward the nobility that supported the former dynasty, the House of Austria, and also the cattlemen.

In Morocco, the Ouazzane Brotherhood ̶ which took a deeply interventionist role in politics and in the Spanish “Africa Wars” of the following century ̶ was then set; in the same way, a bit earlier, brotherhoods played an important role in Andalusia against the French invasion and the secular measures of José Bonaparte’s administration.

It was over those years that the miraculous apparition of Marrakesh’s patron saint, Sidi bel-Abbes took place in Tetouan, which at that time was a land distant from the royal power, and it was administrated by the “Granadans” who founded the city, like the Erzini (Albarracín) and Moriscos like the Torres or Luca families.

A group of gnawas in the Jemaa el-Fnaa square, in Marrakesh ©Xurxo Lobato

New brotherhoods have not stopped emerging ever since, one way or another, and intervening in politics: the Tijaniyyah –founded by al-Tidjani, buried in Fez ̶ played an important role in the Algerians’ rebellion against the Turks, and later on supporting the French administration. The Darqawiyyah, who were founded in a kabyle near Alhucemas, were characterised by their belligerence against the Spanish occupation that resulted in the Protectorate. According to many authors, Abd el-Krim, who defeated the Spanish troops at Annual, was a member of this brotherhood, taking part in the battle wearing their characteristic green turban.

Moussem is the name given in Morocco to street celebrations, and it can refer to an urban, religious celebration, a pilgrimage or a festival. In fact, in those events where the religious and civil spheres mix together, not only in an official way but above all mentally ̶ as it still happens in a big part of Andalusia ̶ few of the events are entirely secular.

In the Mediterranean region, having four distinct seasons, yet a mild climate, the year was kept by following various calendars: the universal, the seasonal, that of the sun and the moon, and thus many patronal feasts were the result of the combinations among them.

In historical cities like Fez, Marrakesh or Rabat, saints and their brotherhoods are linked to the trades, as it happened centuries ago among us too, given that the trade guild had no sense without a religious base and, at the same time, it was an association for the protection and defence of competition and mutual help.

On the day of the festival, the trade association boasts of prosperity through its processions and parades, giving rise to a throng of people in the streets showing off the garments that they are offering to the sanctuary, particularly the velvet embroidered cloth that covers the saint’s sepulchre that is taken in a procession to be shown to the crowd.

Those scenes are very familiar to us, because they occur in our processions, too (it mainly happened in the past) similar events: from the auction to carry the processional floats, to the public donations of tunics or cloaks for the saint’s images, as well as the competition to gather people or shooting fireworks in specific sites related to families or commercial or business organisations.

There are other ceremonial relations with saints to implore their protection which are appended in the vital cycle, like the one of the circumcisions at the Moulay Idriss’ mausoleum, as we mentioned at the beginning. In Tetouan, after the night-time wedding ceremony, while at dawn the palanquin is taking the bride to the groom’s house accompanied by an orchestra, it is customary to pass by Sidi Saidi’s hermitage and knock at the door. Burials of the people who are assigned to brotherhoods use to design their itineraries in order to pass by these places and, also in Tetouan, all corteges stop for a moment before the mausoleum of the Sidi Mandri, born in Granada and founder of the city.

However, the moussems are of particular importance when, as an essential feature, they involve travel, that is to say, when the celebration is focused on the romería or pilgrimage. At the beginning of the last century, Arabist Miguel Asín Palacios wrote in his book Chadilíes y alumbrados (Chadilies and lightings) on the issue of the romería to the shrine of Moulay Abdesslam:

“With no documents but these bustling scenes where devotion melts with profane diversions, it might be difficult to imagine in our days the meaning of the austerity and mysticism that inspired the life and doctrine of that illustrious saint.”

He could have said the same about the celebrations that dot the territory of Andalusia and Spain, the regions of southern Italy, Greece, Mexico, Peru… because they all exist not superficially as they have been often portrayed, in a mix of religion and life, which is what ultimately defines popular religiosity.

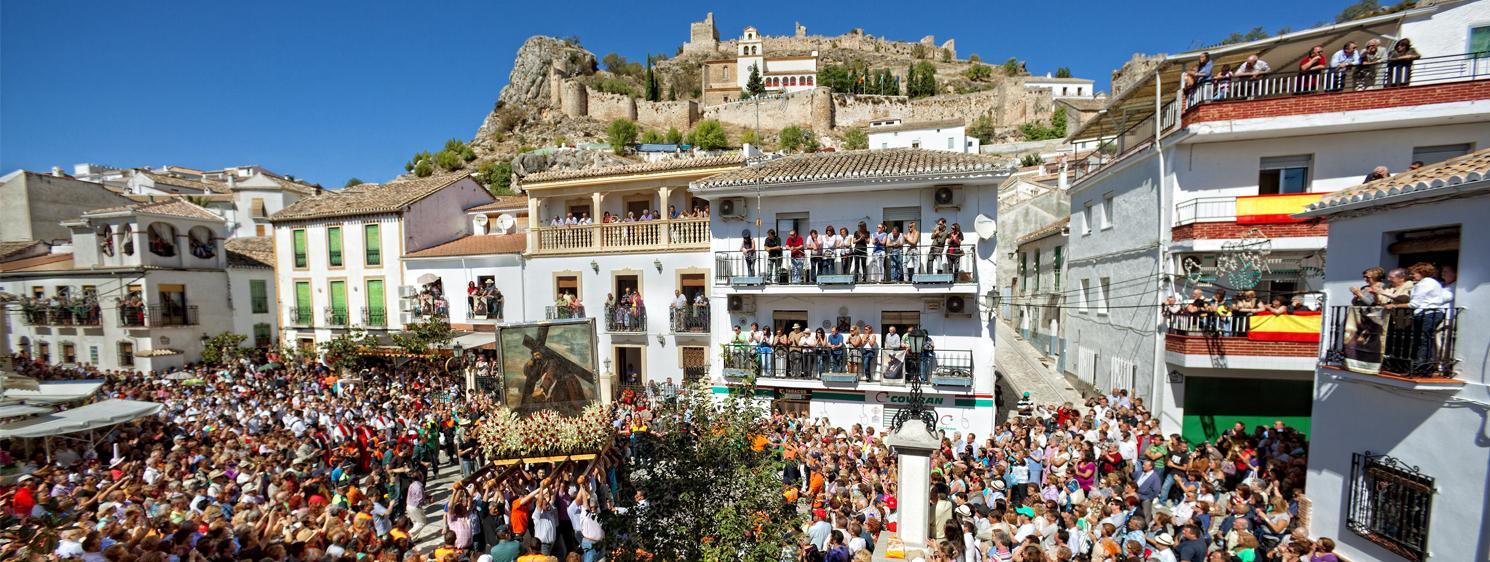

Undertaking a ritual journey is one of the most profound expressions of the human spirit because it has connotations of cleaning, of making a new start, while at the same time it confers sanctity to the summit of a mountain or to an unknown place in the heart of a marshland. To this must be also added the need to look for a partner or to “renew blood” that existed in rural areas composed of small villages; let us remember that the romería of Cristo del Paño in Moclín (Granada) is mirrored in Federico García Lorca’s theatre play Yerma. By linking all these elements, the annual journey of the romería gains meaning. By linking all these elements, the annual journey of the romería gains meaning.

Romería of Cristo del Paño, celebrated in the town of Moclin, in the province of Granada.

In Spain, the majority of these celebrations are subject to the solar calendar, and they are hence related to the finalization of certain agricultural works such as harvests, although there are some, like that El Rocio, which still depend on lunar months.

In the Maghreb, these are marked by the different celebration days of the Muslim year, in particular the Mawlid (Birth of Prophet). In al-Andalus, many should have been the festive events around it too, as kept in Luis de Góngora famous chorus:

Al Gualetehejo

del Señor Alá,

aa, ha, ha.

Hace vosacé

zalema e zalá.

The painter Mariano Bertuchi, who lived in Morocco most of his life, and in contrast to the majority of the “orientalising” of his time who confused Morocco with the court of Harun al-Rashid, has left us wonderful, colourful scenes of Moroccan romerías, similar to those celebrated on this side of the Strait that were depicted by other Andalusian artists.

Some of the pilgrimages that are currently celebrated in Morocco were also described in 1988 by Juan Goytisolo: “The valley next to the hill (near Marrakech) where Leilah Fatima’s remains rest has been transformed into a souk with festive air… the crowd gathering there wandered on improvised paths among kebab stores, stalls of clothes and shoes, butcher shops and shades with vendors of candles and spices… a band of elderly musicians with rustic instruments, families and groups of women cooking or camping in the idle time of summer… the path zigzags and the row of those who come up crosses with the ones coming back from the ziara (visit) to the saint…”.

This portrait might be attributed to any of the many pilgrimages that take place in our territory all four seasons of the year, starting with the Virgin del Mar’s romería in Almería and ending with those of Valme and Cuatrovitas in Seville, that take place in the fall.

The romería is a break in the ordinary, and the atmosphere that permeates them is distinct from the everyday. When this fact is alluded to, it usually leads to the erotic aspects, but the truth is that the change produced involves many more facets: upper-class people decide to disregard rules for some days and become easy-going, while those of lower social levels look their best wearing even jewellery. Everybody will boast wealth and prodigality in an atmosphere of warm and general hospitality towards everyone.

We go back to Goytisolo again in this regard: “…the atmosphere of freedom existing (he refers to a romería in El-Jadida) reciprocates the general characteristics of some moussem: women and young girls walk peacefully by night, and they stop to chat with strangers, accepting their courting and gallantry with pleasure. Encounters, romances, nocturnal dates, are all sometimes set up using sign language, sheltered by the sanctity of the place, and the honoured ladies are not forced to justify their absence…”.

In fact, it is all about spending a few days in an atmosphere that allows the transgression of the rigid conventions that rule all year long. The physical journey is linked to an inner one which is the true origin of the “addiction” these events produce in people ̶ both in the Maghreb and in Andalusia ̶ a sort of a mystical catharsis where all the accumulated feelings discharge and give free reign to emotion.

A French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu, wrote fifty years ago, in Sociologies de l’Argelie:

“In the Islamic rural communities […] the collective experience constitutes the original experience of the sacred. The devotion of the head of household, the symbol of the community and the priest of domestic religion, the worship of the ancestors […], the “baraka”, a mysterious and beneficent power […] magical practices aimed at ensuring the fertility of fields and women […], here it is a rural religion […] which by its emphasis on the rite makes of life kind of an uninterrupted liturgy”.

[…] The God of the Koranic dogma remains far away, inaccessible and impenetrable, and the man of the people is in need of bringing near to him the approach of divinity […]. Marabouts and brotherhoods offer a religion that addresses the heart and the imagination”.

He might have written the same referring to the old lands of al-Andalus.

Florencio Sayago,

is a Historian