Loja, amid snow and wheat

As we follow the Route of Washington Irving and we get to Loja, it is hard to imagine it sheltered by gorges so admiringly described by Andalusian poets and the Romantic travellers.

It is harder still to go back to envision an imposing castle, rising over a high hill and dominating the scene; we can only imagine its power by gazing at the ruins of a whole string of towers, named Homage, Ochavada, Almenas, Maestre, Agua, Basurto… and, rather than strolling among them, observing what remains of the once-grand arch of its entrance, of the gate of the Jaufín quarter, of the large water tank, of its proud dome.

Today, visually, the city, even though it is right the opposite of flat, looks sunken in a kind of geographical depression, captured by the eye of the bystander, defenceless before the critical gaze of anyone looking for the usual urban pollution in these times of concrete and brick. But, despite everything, things do not come out badly for this guardian, this incorruptible sentinel of Nasrid Granada that would succumb to the troops of Ferdinand III before Alhamar from Arjona became an ally of the Castilians and would resist later against all odds, thanks to its standard-bearer al-Attar, amid the vicissitudes of the civil wars.

The ubiquitous narrative history of the 16th, 18th and even the 19th centuries finds its source in Turdetania, or at least in Rome. But paintings found in nearby caves show that the human presence in this spot was much earlier, although the city of Loja, or that which can be called a city, was not Loja as such until the years when the Umayyads dreamt of healing the wound caused by the rebellion of theMuwallad Umar ibn Hafsun, which was an open sore for many decades.

That was a confusing and uncertain time whenthe historian Al-Khushani (10th century, Qayrawan- Cordoba) described in a colourful way, with individuals that had not learnt Arabic yet, people who still bore Gothic and Latin family names, while the emirs from Cordoba built the capitals of a political beehive through treatises with Christian warlords. Here, in this moment, was when Loja was truly born, that today is a valley and yesterday included a peak.

But one should not exaggerate the theory on its close origins because really they are even more: the city we see today is, above all, a Renaissance one that shatters the saying that any time in the past was better. If until 1492 the site was mainly a castle ̶ and a bunch of houses that hung down the rugged slopes below ̶ since that time, when there was nothing to be defended on one side or the other, the plain ̶ the fertile land ̶ shifted from being dangerous towards making it productive; those who built castles changed them for palaces and who used obstructions to defend the river’s fords built bridges, for there were no enemies to impede, but merchandise for distant destinations and travellers with many days on the road and still ahead.

View of the Barrancón Bridge, constructed in the 19th century by students of the School of Eiffel.

The graceful bridge over a Genil River that is ever travelling from the far reaches of the snow and that with each bend approaches the fields of wheat sits in the middle of the valley, between the mountains that shelter Loja, between the road that comes from Seville and that from Granada, and the first slopes of the area of the old medina.

The imprints of that Loja of Al-Andalus hardly remain anymore in the mass of its castle and the whitewashed houses of its neighbourhood, but from those slopes downward, the stone style prevails in constructions from the end of the 15th century and in the 16th which was also a Golden Age for Loja. That was when the churches of Santa Catalina and San Gabriel were raised, designed by no more and no less than the master Diego de Siloé, and that of La Encarnación was started on the plot where the old mosque al-jam’a. They were symbols of the new religious power, the new power overall, in times where in every culturethe concept of a celestial city held sway and religions had monarchs in their service.

Inscription in Arabic on the door of the Homage Tower.

In Plaza de Arriba, the Council organised the city as fast as the ones that a quarter of a century later were arranged in America, constructing the city halls and the Depository of Wheat (Alhorí del Trigo) ̶ the first in Loja ̶ relentlessly building a public store (Almona) a bread centre (Alhóndiga del Pan), butcher shops, fish store, houses of meals, mills, hospitals for epidemies sent by God and wounds caused by men… and the new granary, which we can still be seen with its beautiful arcades and stone coats of arms that would end up housing inside several other buildings.

These were the times when town councils still firmly believed they were descendants of the old Roman senate, times when ̶ once the mythical Al-Andalus was cast-off ̶ everyone was striving to become an offspring of Caesar and the bigwigs of the old empire.

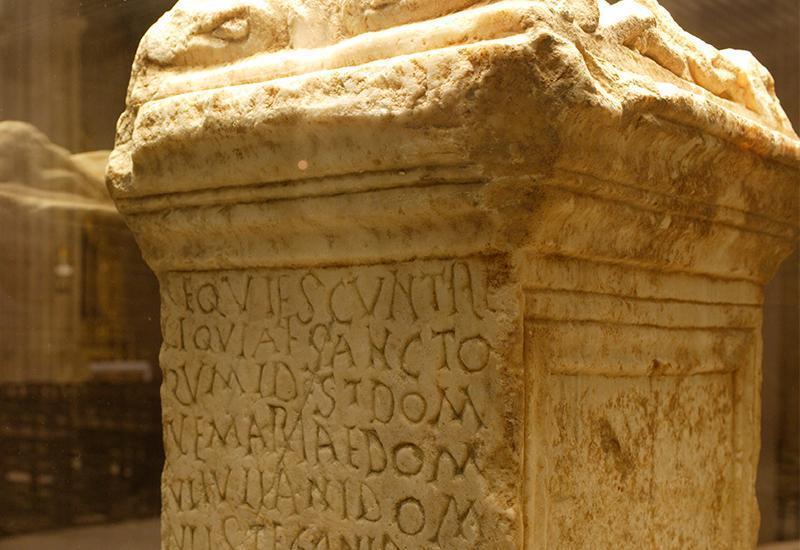

Quadrilateral tombstone from a Paleo-Christian sepulchre made of Genoa marble, with a Latin inscription. On display in the Major Church of La Encarnación.

With prosperity came also friars and nuns looking for alms based on the rule of the fraticello, that accommodated in the convents of San Francisco and Santa Clara, this latter founded by a Franciscan cardinal, as can be expected, Hernando de Talavera, who was the first and opposite of another cardinal, Gonzalo Jiménez de Cisneros, in promoting an inclusive religion by forming orchestras and setting up choirs with Moriscos who added musical scales of an Eastern style to the religious ceremonies, and were even permitted the luxury and freedom –the Council of Trent’s rigour had not yet arrived– of introducing into the liturgy prayers and sentences in Arabic.

In the nuns’ monastery we can still admire the flamboyant Gothic façade of the church and the beautiful Mudejar coffered ceiling of its interior. Of that of the monks, disentitled by the church at the beginning of the second third of the 19th century, the arches of its cloister remain, indelibly linked to the brotherhood of Vera Cruz.

Ceiling and vault in the church of San Gabriel

Detail of the decoratione in the vault of the church of San Gabriel.

Façade of the Hermitage of San Roque.

Vault of the sacristy (detail) in the hermitage of San Roque

For the popular devotion chapels remained, scattered from downtown to the outskirts and open lands: those of la Caridad (Mercy), San Roque and many others that have been crushed by the mill of time, negligence, and the convulsions of a history that gave peace of mind to no one. Because in the 18th century, and mainly in the 19th, times of famine came not only in Loja, but all over Andalusia, which depended on the rising and falling fortunes of the economics of cereals farming, which was loved and occasionally defeated by father and tyrant sun.

First appeared the dawn rosaries as a covert protest on the measures undertaken by the Enlightenment theoreticians and the practical despots, and later, the rural uprisings like that of the veterinary surgeon Pérez del Álamo, kept the state in check over many days before being defeated through the logic of rifles. Their leaders were the sons of Loja to whom a monument will never be built.

Ibn al-Khatib is an illustrious son of Loja. Famous multifaceted writer and powerful vizier of the 14th century, was as brave with the pen as with the sword, as shown by his official title as minister: “the double vizier” (“Dhu-al-Wizaratayn”).

“The sultan [Muhammad V], he confessed, has assigned to me to ensure his secret chancery… a post reinforced with the command (of armies), the management of the vizierate, the missions of embassies before the kings… he has placed in my hands his seal and his sword.”

It is known by every inhabitant of Fes, and if they notice that you are keen on listening to accounts of the subject, they tell you the story or the legend of the Gate: Palace intrigues were what led Ibn al-Khatib to his death. It is said that he was executed in his cell and to be thrown afterwards onto the fire that was placed in that Gate which he lit with the torch of his body. And the Gate will remain so: forever lit with the memories of his wisdom in all fields of culture, with the legacy of everything he left, which we still enjoy without knowing it.

For, without knowing it, when somebody composes a seguidilla (Spanish popular chant) or a ballad for any celebration, such as the “crosses of flowering May” in Loja, for instance, they are following a line marked out by ibn al-Khatib of Loja. He was also a friend to Ibn Khaldun, to whom he welcomed, maybe in Loja, when he was nearing Granada, now more than 750 years ago.

By Antonio Zoido. Writer