Bibarrambla, from al-Andalus to the Christian era

Bib al-Rambla, Bib-Ramla, or Bibarrambla, as this square was called with different names by one or the other. The Christians, after their conquest of Granada, must have been attracted by the mystery of such a name, strange and difficult to pronounce, which the Catholic Monarchs patiently assumed. It is in this way that we have seen it in the city plans throughout history, since Plataforma de la Ciudad de Granada, drawn by Ambrosio de Vico in 1616.

The Alhambra, with its omnipresence, has diminish the beauty of other corners of Granada. Such is the case of this square, which is not like other squares in other cities of Spain. Bibarrambla is a square that is special and spatial that pulls at us not only from the ground, but also from its sky above, perforated by the silhouette of the imposing mass of the cathedral, the delicate figure of the Torre de la Vela or the immense Sierra Nevada.

View of Bibarrambla Square as it looks today.

Therefore, Bibarrambla is a square to be seen in every direction and from all angles. And we would not do badly also listen to it, when the sparrows, with their shrill chirp, announce to us that the evening has arrived, the moment in which they return to shelter among the leaves of the lime trees. A square so alive may look to us like a new one, but Bibarrambla is a square so old that its eyes have seen the passing of the history of Granada.

According to oldest maps, in the times of al-Andalus the dimensions of the square were smaller, maybe simply those necessary to host the stalls of fruit and fried-food vendors, or those of parchment that lived alongside water carriers and snake charmers.

It is foreseeable that the square could have already existed when sultan Muhammad b. Yusuf ibn Nasr, popularly called Alhamar, was established in Granada in 1235, since the area had been previously inhabited by Muslims.

When Granada was consolidated as a city, it had to enlarge its limits. Another wall was added to the one that already existed since Zirid times, from which we still have important remains. The first one persisted attached to the square at its west, where opened the main gate named Puerta de Bib-Rambla (Gate of Bib-Rambla) by derivation. Architect Antonio Orihuela Uzal tells us that this wall section must be from the 11th century: “It can be deduced, according to Memories of Abd Allah, the last Zirid king’s autobiography, that he succeeded in closing totally the medina’s walled enclosure to preserve it from the Almoravids’ attacks.”

Stretch of the wall on the north-west side of the Granadan district of the Albaicín. It was built by the Zirids and later expanded during the Nasrid period.

The name made reference to a sandbank close to the square that stretched up to the Darro river, being surrounded by other streets that made it lively enough so as to become the most populated square of the medina. Thus, its east side led to the souk dedicated to clothes, Suq alqarraqin, that finally resulted in the current word Zacatín, and on the north-west side the alcaiceria, al-qaysariyya, as the people from al-Andalus of those times would name it, a spices and silk market, as well as luxury goods that provided an important flow of sellers and buyers.

Whereas it is easy to imagine how the hustle and bustle of the souks and Arab markets was inside the square, on the outside we find a labyrinth of streets that emerged due to the expansion of the shops. They were streets that closed at night to prevent thievery and looting, and they returned to life in the morning under the impassive eye of the Lord of the Souk, the almotacén (public employee who controlled weights and measurements), and the presence of the Mosque, whose Qibla wall was opposite the alcaicería.

In close proximity to the square, Yusuf I built the Madrasa (medersa or Koranic school) in 1349, whose oratory we enjoy today in Oficios street. This fact revealed that wisdom had entered the city, which bestowed a place for the wise men’s thoughts which no doubt were shared in the first square of the city of Garnata.

Outside of the building which hosts the Madrasa.

The oratory with the mihrab in the Madrasa.

Merchants were, little by little, giving name to the streets that surrounded the square, after their different trades, like the bakers’ street (paneros), silk workers (sederos), dyers (tintoreros), upholsterers (tapiceros)… whose names are still in use today.

Yet, the square main entrance was located, as we have already said, in the southwest area. It consisted of a magnificent gate which was to remain controversial throughout the centuries.

According to Antonio Orihuela and Juan Castilla Brazales, co-authors of the essential book, En busca de la Granada andalusí, (“In Search of the al-Andalus’ Granada”) the gate went through different names: “…Christians named it interchangeably in Arabic, or changing it to the Castilian form Bibarrambla… and other names such as Puerta de las Orejas (gate of the ears), Puerta de las Manos (gate of the hands) and Puerta de los Cuchillos (gate of the knives). Christians said they named it this way due to the fact of the place being where the mutilated limbs of the malefactors accused of criminal offences were publicly exposed. Regarding the last of these appellations, there were diverse versions that related it to the arms seized by the law, while others stated that it was due to the existence of the cuchillería (cutlery market) near the Gate.”

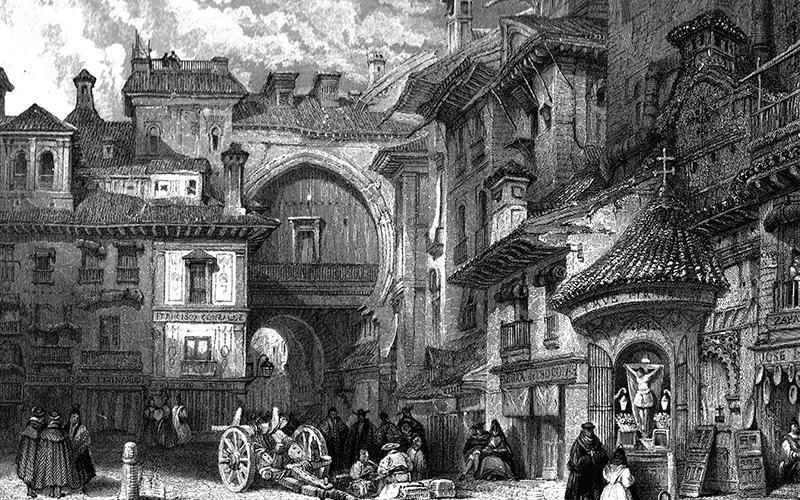

In relation to its similarity to the Gate of Justice of the Alhambra, scholars have determined that it belongs to the same time, that is to say, the year 1348, a year of plague (black death) in Spain and half of Europe. Despite this, the gate should have looked dashingly in the corner of the square. Leopoldo Torres Balbás defined it as follows: “It was opening in a square tower. In its exterior front it boasts a large sharp pointed horseshoe arch whose keystones are made of loamy stone from the Elvira Mountain range. Behind this arch, there was another one, a segmental arch that gave way to the adarve (battlement walkway) and kept on along an open-air space. The door arch opened to a passage, divided transversally by a pointed brick arch, in two sections. The last arch opened to the square directly from a second section, but we do not know if this was the primitive disposition or if earlier the gate expanded on a bent-entrance ̶ like the Gate of Justice and many others Muslim gates ̶ , and if this last part could have been demolished to make the access easier.”

English painter David Roberts drew it in a delicious way, describing the symbiosis of the monument with the houses, already Christian by that time. However, a bit later, the controversy over he demolition of the gate began to divide Granada. After long struggles among advocates and detractors of that barbarity, the Municipality of Granada secured the authorisation for its demolition. The year was 1884. And such was the happiness of the neighbours that they celebrated the final decision by shooting rockets. This was a regrettable memory of our history that unfortunately has taken place in our country over and over. Antonio Gallego Burín lamented in 1919 on the idea that institutions had about demolishing the Corral del Carbón (Coal Yard) and the Casa de los Córdoba (The Córdoba family’s House). Luckily, the indefatigable Torres Balbás rescued from the collection of a museum the remains of the Puerta de Bibarrambla to restore it and be placed in the woods of the Alhambra. Today, its presence amazes us, in the loneliness of the Sabika hill, only forgotten by those who do not know it.

Queen Elisabeth and King Ferdinand must have chosen Bibarrambla as a place for citizens to meet, as there was in the city no larger square. It is true that the Campo del Príncipe (Champ of the Prince) competed in terms of importance, but their respective competences were soon divided, the Campo del Príncipe was reserved for ludic activities, such as and tournaments and games, leaving Bibarrambla for bullfights.

Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, the confessor to the Catholic Queen, might have sensed the importance that this square would have in the future of Granada. In the same way that it was adorned in feasts and celebrations, it was clouded by their cruelties, for it was there where he undertook his autos-da-fé and also where he burned eighty thousand books from the Muslim university of Granada, arguing that they all were the Koran. He told but the plain truth, as for him they all should be regarded as Korans, even the treatises on mathematics.

The different versions of the Plataforma de la ciudad de Granada (Platform of the city of Granada) shows a square marked with a small gibbet, a symbol indicating that the square was the place where a scaffold stood over centuries. Yet, “This symbol should not be linked necessarily to the Inquisition’s autos-da-fé, Antonio Orihuela tells us: “The death penalty was very frequent at those times. In Anales de Granada (Annals of Granada), by Francisco Henríquez de Jorquera, for instance, the death penalty sentence for sodomy is documented in the mid-18th century.”

Detail of the “Vico’s Platform”, showing the location of Bibarrambla Square.

Those were times of refurbishment for the city. Muslim cemeteries, once dismantled, provided new spaces. The Jewish quarter was demolished. Christians wanted large squares as manifestations of their newly powerful situation, not leaving aside the economic aspect, what motivated the reorganization of trades. In this way, the square was expanded toward the fishmongers and the tanneries areas which at the time ran up to what today is the Corral del Carbón. Tough bargaining over the remodelling conditions, for Luis Hurtado de Mendoza y Pacheco, at the time the Count of Tendilla, and who owned the majority of the square’s land, ultimately resulted in support of the City Hall that favoured him to the fullest extent.

Fernando Acale Sánchez tells us in his book Plazas y paseos de Granada (De la remodelación cristiana de los espacios musulmanes a los proyectos de jardines en el ochocientos) (“Squares and Promenades in Granada: from the Christian Renovation of Muslim spaces to the 1800 garden projects”): “The stretch of the wall was demolished in the junction where Mesones Street and the square meet, despite its proximity to the Gate of the Arenal (that is the Gate of Bibarrambla), dividing it into two the space for butcheries. This arch started to be known as Gate of the Magdalena, and later on as Puerta de las Cucharas (Gate of the Spoons)”, a name that has prevailed in the memory of the current street plans of Granada.

In 1583 the Casa de los Miradores was built, which hosted the Royal Customs for spices, clothes and linen, and for alcatifas (fine tapestries and carpets), and also the city hall offices were located there. The building was burnt to the ground in the last third of the 19th century.

Acale Sánchez mentions in his book the views on the square described by the Venetian ambassador and historian, Andrea Navagiero, and thus we can imagine how it was in the first half of the 16th century, as: “a beautiful and large open area, squared and regular, although a bit longer than wider, with a delightful fountain in one of its angles with many water jets that pour the water into a large and charming basin.”

The fountain that Navagiero referred to must have been the one known as “del leoncillo” (the little lion) which was transferred as time went by to a corner in the square, by Pescaderia street. In this way they got more space for the usual celebrations, above all the Corpus Christi, established by the Catholic Monarchs in 1501, which was a very deep-rooted tradition. The fountain was demolished in 1837 when it was already in a pitiable condition.

Luckily, the indefatigable Torres Balbás rescued from the collection of a museum the remains of the Puerta de Bibarrambla to restore it and placed it in the woods of the Alhambra. Today, its presence amazes us in the loneliness of the Sabika hill, only forgotten by those who do not know about it.

We can deduce that the square kept its current dimensions throughout the 18th century, and that the subsequent transformations mostly took place for decorative reasons rather than urban redevelopment. In 1750 the square provided for a permanent market, and its central axis soon started to fill with plenty of stalls, an image that should not be very different to the one painted by Muriel almost a century later, in 1834, which is kept in the Museum Casa de los Tiros of Granada.

Acale remarks: “The square’s configuration was meant to be a market, in the 19th-century sense of the word, open-air, with a street plan that allowed the stalls sufficient space. In 1750 a set of wooden cabins was built in the centre of the square that served, under the aegis of the city police, to exert better control over commerce while at the same time allocating economic benefit to the city.

At that time, Bibarrambla was not only dismantled, but it was also subjected to changes on the occasion of the Corpus Christi feasts, like that famous one celebrated in 1760, which was so pompous that it greatly exceeded any film set.

In the 19th century, Granada, like other Spanish cities, suffered an urban rush, as a result of increasing open mind, of repeating political changes, and of course the effects of disentailment. At the very beginning of the century, another outcome was to transform the city of Granada. We are speaking of the fires, that continuously menaced the beauty of its houses and monuments. The one that took place on 19th July 1809 destroyed the cabins in the square and spread to the Casa de los Miradores, although the damage caused was not irretrievable. Another fire affected the nearby alcaicería some years later. The vendors’ booths, rendered useless, had to be temporarily relocated to the squares of La Trinidad and San Antón. In 1836, the nearby convents of San Agustín and Las Capuchinas were demolished, and the booths rearranged, which restored Bibarrambla Square to its former splendour, when it was the pride of its flaneurs, now having a large central space that only in the 40s of the 20th century was invaded by florists’ stalls.

But every square has to coexist with a monument. After the demolition of the Fuente del Leoncillo, a monument to commemorate the recently instituted Spanish Constitution of 1812 was built, designed by Juan Pugnaire, who stated in 1855: “Every city has or must have a main square, a square for ceremonies and public events. In Granada, this square should be Bibarrambla, because of its historic memories and its central location.”

González Sevilla and Juan de Dios Bertuchi’s 1894 city plan gives us a very realistic picture of the streets that surrounded the square. This plan had two versions, one of them, as their authors said, was devoted to be “of true utility to the foreigner who visits this city and no less for its inhabitants. Granada turned into a meeting point for intellectuals and travellers, surely encouraged by the Romantic image Washington Irving had pictured of it.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, the square had no balconies anymore, nor arcades nor fountains. Almost forty years had to pass by until the Bibarrambla square had its street flower stands and another fountain. This was to take the place of the statue of Fray Luis de Granada, which was placed there in 1910. Thanks to Antonio Gallego Burín, the statue of the saint was finally placed in Santo Domingo square, where it remains nowadays, while the fountain that today adorns the square, known as Fuente de los Gigantones (Fountain of Giants) was then placed in Bibarrambla square.

Fountain of Giants.

We can easily imagine Granada in its happiest days, those prior to the Civil War, enjoyed by its students, poets, and doctors, by its painters and politicians. Some would walk through Bibarrambla on their way to the nearby Plaza de la Universidad, others would cross it to attend the social gathering in the Café Alameda at the Plaza del Campillo.

In the fifties the city underwent many and diverse changes, some of them very close to the square, now such a central place, and it will not be until the seventies when Bibarrambla experiments the definitive change, the last and unique one that a square of the future must experience: pedestrianisation.

Now the square is the most visited in Granada and the most sought-after one. In the morning, in the afternoon or by night, the terraces on Bibarrambla or Bib-Ramla or Bib-Rambla will be full of tourists, Granadans, or those that, not being so, feel a little like both. They will have an ice cream if it is summer; a hot coffee or chocolate if it is winter. And in the evening, like every day, Bibarrambla Square will fill with flocks of starlings with their strident call, until silence takes hold of the square, under the intense and blunt gaze of the Cathedral tower.

By Carolina Molina.

Journalist and writer of historical novel.

Bibliography:

Acale Sánchez, Fernando. Plazas y paseos de Granada (De la remodelación cristiana de los espacios musulmanes a los proyectos de jardines en el ochocientos). Universidad de Granada/Editorial Atrio. Granada, 2005.

Calatrava, Juan and Mario Ruiz Morales. Los planos de Granada (1500-1909). Diputación de Granada. Granada, 2005.

Castilla Brazales, Juan and Antonio Orihuela Uzal. En busca de la Granada andalusí. Editorial Comares. Granada, 2002.

Gibson, Ian.. En Granada… su Granada. Diputación Provincial de Granada. Granada, 1997.

Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. Crónica de la España musulmana. Obra dispersa. Instituto de España, 1981.