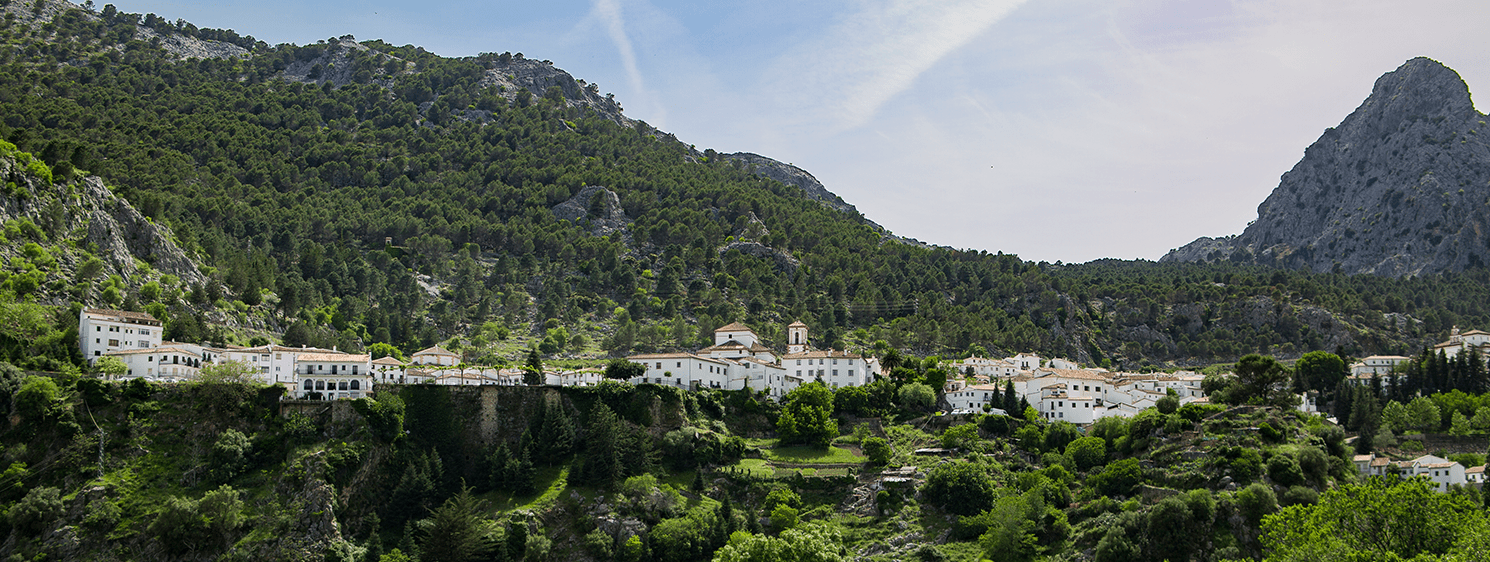

Grazalema, en el envés de la Historia

The National Park of the Grazalema Mountains is home of the famous Pueblos Blancos (White Villages), of great natural beauty and long history. Grazalema, in The Route of Almoravids and Almohads is included in the list of the most beautiful villages in Spain..

The landscape of farmlands ends as soon as we spot Villamartín; then in the surrounding hills around the tower of Pajarete rule the meadows, and out the blue, with a simple turn to the left at the urban limit of El Bosque, we enter another world. The road goes on to Benamahoma, a hamlet of Grazalema, keeping up with the ravine that was formed over millennia by the Majaceite River, which despite being a tributary lords over the greatness of the Guadalete, theRiver of Blood, of Treason, according to the many names that make up the myths of early Al-Andalus.

When the road has run out of almost all its curves, we arrive to Puerto del Boyar, apparently a crossroads. But, in fact, it is a communications hub linking territories, the back door of the provinces of Cádiz, Málaga, Córdoba, Sevilla and even Jaén, the “invisible border” in the long co-existence between the Castilian Andalusia and that of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada. It is the line of unknown battles in the Spanish War of Independence against France, a silent shelter for bandits and maquis … the dark side of big struggles. And it marks the place that receives the maximum rainfall –2,000 litres per year– in the Iberian Peninsula.

It is at that point where Grazalema spreads its roofs as if they were the cloths put to dry in the sun by a laundress. Above them all, the horizon stretches up to the raised plateau after which Acinipo, Ronda la Vieja (Old Ronda), appears barely perceptible. It was named so in the Renaissance by those who wanted to find an essential Greek-Latin origin in our important cities. Behind us, the peak of Saint Cristobal acts like a weathercock, a sign that makes this town one of the rainiest in Spain and made of it a textile emporium in the 17th and 18th centuries, thanks to the water that these protecting mounts held.

That prosperity changed it into a uniform village, without palaces nor cottages, full of houses of similar heights that still retain those elements promoted by the House of Arcos, which conquered the village when Nasrid Granada was dying: the arch from Arcos de la Frontera, half Tudor, half flamboyant, still remains in the gates, of which some are made of stone and some of brick, all of them whitewashed with lime of many vintages.

However, higher up, in the decorative elements of the façade, the broken pediment of a late popular Baroque style and the window’s trellis are sons of an art that has been swallowed up little by little. This art is based on the deep observation of the stately homes to ultimately be able to build one for oneself with the same canons: they are the same rules that gave shape to the Andalusian landscape, with its houses and trees, its gates and the flower beds which frame them accordingly, each in its right place.

The square is overlooked by a church, that of the Aurora. Its façade, with large facings and flat towers, resembles a Mexican church, although they are the same as in the neighbouring villages like Zahara, over which the Duchy also ruled. The play of roofs descending from its octagonal cupola is simply beautiful. It rises far beyond the height of the houses that surround it, but it is not out of tune: there are rules that, despite being against the rules, still prevail.

The church has not been in use for a long time; it may be in ruins, but the sweet and Baroque chants of the auroreros still resonate in its atmosphere:

To God thanks that we arrived

At the divine temple already finishing

singings in the streets to Dawn

And forgive us Lord our faults,

We have just

knocked the doors singing

For them to join us to pray the rosary…

These rare verses known as of “pie quebrado” were included by cinema director Saura in his movie Llanto por un bandido (Lament for a bandit), as the soundtrack of the scene of José María el Tempranillo’s wedding night. Because, it may sound a cliché, here was married José María Jiménez and, in the opposite side of the square, nobody knows why there was always a street bearing his name. Perhaps he is the only bandit with a street named for him in all of Andalusia, but like noblesse, the myth also obliges. In the myth of that time, romantic bandits and the campanilleros were a crossbreed that resulted in the stereotype of the so called “people of bronze”, that has endured as a synonym for hardened people, although at the beginning this only referred to the groups that sung at dawn on the festival days accompanied by the noise made by mortars (which were normally made of bronze), chimes and rattles.

The streets that make thepuzzle of houses all identical yet all different, all distil the reflections of sun on this morning of festival, split up to give way to cosy little squares, always placed in front, behind or by a church or an old hospital. Up there, where almost half a century ago there were only huts of poor day labourers, still rises the belfry ̶ red and white ̶ of San José, which was a Carmelite convent.

According to the popular sayings, it was there, in the small plain that stretches before the descent to the oldest part of Grazalema, where the “toro de cuerda” had its origin. This is a popular corrida (bullfight) that took place in every wedding party and on certain days and became so popular that its scenes are engraved in the choir stalls of the cathedral of Seville. Although it has declined in many places, still today it is a distinctive feature here in Palm Sunday and, however strange, in Arcos de la Frontera too. Someday, the influence of the manors in the personality of the villages should be studied.

Church of San Juan de Letrán

Going down in direction to the city centre, the slope allows the walker to encounter the church of San Juan, which surely was a mosque before, given the remains from al-Andalus that have been found, and because the builders of the current tower followed the system of overlapping sections as in many of our minarets, as for instance, that of the mosque of Córdoba.

Then, through a passage full of windows with flowerpots, we arrive the place where once stood the old gate of the village. A small lane leads inexorably to the Roman road that some bold scholar has named “Nasrid Road”. From here, the landscape opens, and the winding path known as Camino Ballato –“cobblestone” in Arabic, the same term that ended up giving name to the “Ruta de la Plata”, the Roman road which connects Seville and Astorga ̶ points towards the direction of Acinipo and Ronda, once we pass a public wash house, a hermitage and the blanket factory that establishes, as if to summarize, the splendour of textile from days of old.

Roman road

As in its flat towers of the church of the Aurora, Grazalema is here again related to America: blankets and horsemen’s ponchos that, as in many songs and ceremonies, are the authentic products of the “ida y vuelta” (coming and going) phenomenon, from which nobody will ever know if they started here or there, nor even who influenced whom.

The square, presided by the city hall, has a large fountain from which spouts flow from the mouths of four podgy faces carved in stone, surrounded by the expansive shade provided by an extraordinary tree: the pinsapo or Spanish fir.

When in the middle of 1800 Pascual Madoz was gathering information for his Historic-Geographic Dictionary of Spain, the informant from Grazalema did not even mention this tree in his account of the region’s resources.

Forty years ago, the whole Sierra del Pinar (Pinegrove Mountains), hill after hill, was no more than what poet Miguel Hernández once described by: “[…] a land of poor labourers and workers.” Nobody believed in its wealth, not from public nor private spheres. Year after year, the waters of the mountain streams swept away the pinsapos that were along its indomitable course into the depth of the Valle (Valley) del Revés. Today a Nature Park, it provides the most sustainable resources of the area.

The mountains of Grazalema have the largest concentration of Spanish firs, pinsapos, the only species of tree which managed to survive to the last glaciation.

The Pinsapo trees are very tall, up to an average thirty metres. They grow almost exclusively in the mountains of Málaga and Cádiz, as well as in certain areas in the Rif Mountains in Morocco. Considered as the “Spanish fir”, it is a protected species, in areas as, among others, the Grazalema Mountains, where it is even on the flag of the town city.

The Park, that in its unbridled area of pinsapos has remained as it was, in the semi-chaotic state provided by the wrestling of nature, which has given a beauty and a rampant life that no other natural space in Andalusia has, grants the grace of an unforgettable vision to the fortunate ones who traverse the path that covers it from end to end. In the meantime, Grazalema has domesticated the tree and raised it to the status of totemic. Not only has it been included in its coat of arms, but also it is displayed all over its plazas and street corners. Upon our return we see it, increasingly vigorous in the curves of the road that takes us to Benamahoma, which not much time ago was only “La Huerta” (The Orchard). Because it is right there that the peak of San Cristobal, like Lorca’s character of Cristobalón , loaded with clouds like wineskins, that is made flow of the water that is kept in the internal nooks of these karstic mountains.

Benamahoma, where the Majaceite River springs.

MajaceiteRiver

In Benamahoma, the source of the spring that gives birth to the Majaceite River, which tirelessly sends to the fields 158 gallons of water per second, is a sacred place with Saint Anthony as protector and symbol of sort of a singular hylomorphism that is found in the celebration of Moros y Cristianos (Moos and Christians) its annual liturgy.

If someone decides to travel the distance between Benamahoma and El Bosque, following the water’s course, it will be understood how strong this river is, which lends its power to the Guadalete and gives fame to it, as did Grazalema throughout its history; everything has its front and back.

By Antonio Zoido

Writer