Jerez, city of three worlds

Jerez de la Frontera is something more than wine, flamenco and horses -either thoroughbred or those of power in motorbikes. Its records get across far different periods, the most outstanding of which, al-Andalus, becomes evident in the Route of Almoravids and Almohads.

On the afternoon we arrived, they fled Jerez, as if terrified, thousand of horses all locked down in Harley Davidson, BMW or Kawasaki motorbikes. They had finished the races that brought them together here, every year, like a modern coven with no more witchcraft than that of mechanics and friendship, a countless crowd of bikers from all over Europe, and while the city was getting sleepy it was like the silence that follows the battle.

Now, silence was impossed by the mist on a Sunday morning in September, without even having recovered from summer holidays, still not daring to inaugurate the autumn holiday.

At the base of the old road to Medina Sidonia, the route of the toro bravo (fighting bull) from which Jerez is the gateway, the Cartuja also imposed its silence on the courtyards leading to the church. Its very innocent appearance makes us believe that it had nothing to do with the history of Jerez, which now only prides itself on the horse, making of it one of this city’s three worlds, which it has turned into its totemic animal, adorning avenues, streets and squares.

They are everywhere, except here, the point of departure of the studs that take place in all the ceremonies in the European royal courts, starting with the Imperial of Vienna, whose only living remains are the Spanische Reitschule, the Escuela Española de Equitación (Spanish Riding School), in the heart of the Hofburg.

Carthusian were the horses in the paintings of Velázquez and so was the one on which Philippe III rides in the Plaza Mayor in Madrid. Now all that reigns here is the silence of Hamlet, although Jerez is already waking up, filling the square of the old market of Doña Blanca. Right there, the circle of another of its three worlds still rises: the imposing store featured in all the commercial advertising prints in the 1920’s. Its interior was centred by a pyramid made of bottles of “cognac”, later condemned to become “brandy”, the founder of all the others, immortalized by Federico García Lorca in his Romancero Gitano (Gipsy Ballads):

… behind goes Pedro Domecq

Accompanied by three Persian sultans.

The half-moon yearned for

A rapture of a stork.

Also nearby, Villamaría theatre stands, built for a bourgeoisie which did not mind challenging their cousins in the big European capitals. Now, all year round, flamenco music challenges operas and symphonic orchestras, and in February and March it is only devoted to a Festival which has gained a place among the most important in Jerez.

Jerez always featured all types of flamenco because the world of flamenco also belongs to it. Richard Ford, before mid-19th century, was not especially keen on its happy plays, judging them as not very refined, but in the end, it is from there that the flair which with the city is identified comes from, to the extent that here is where the last achievement of the arte cañí: la peña de guardia (an “on-call” flamenco club) has been invented, which like a pharmacy, give succour to those who come glutted with sounds and dances.

A little further, the Arenal keeps other echoes: those of the jousting and tournaments and bullfights on horse and the game of spears and rods where the riders from Jerez competed. Now it is the heart of the city, a heart that over the centuries has needed many surgeries, and this is why it looks so new and overhauled when, it is sure that the view of this flat surface was very much like that of Chinchón: in the lower part the plain was framed by pavements with porticoes, and the church of San Miguel and the Alcázar (Citadel) in the upper side.

Citadel. Jerez de la Frontera, (Cádiz)

The church ̶ with the atrium and the belfry all of one piece, like that of Santiago, located in one of the most flamenco neighbourhoods ̶ has an altarpice by Martínez Montañés featuring an archangel sending Lucifer to hell. San Miguel is above, as envisaged in the theological correction, and the other one below, sharing space with the rest of convicts and the priest who now say mass for families dressed in their Sunday best. Would Fernando Artacho be right when he writes in The enlighted’s gouge about the sculptor’s membership to the Brotherhood of Granada, thus making the altarpiece actually an irony or a critic?

The alcázar (citadel) is, as it were, across the street, overlooking the wine cellars, the old and the new town hall, the collegiate church… In reality, it is an impossible Almohad acropolis, which almost from its gateway offers us a Muslim oratory, a very rare room that even keeps the minaret unabated, thanks to having been covered over the centuries by other styles of less value, according to the restorer. And the mill, carefully restored, with its whole cyclopean beam. And the aljama (the community’s mosque) , beyond the garden, by the other door once named “the country’s door”, with its halls crowned with stars.

Walking down the stairs, where the parapet of the moat might have been, we can go down to reach the collegiate church, which today is a cathedral, and before was a mosque. Its minaret, now separated from the Late-Baroque building, keeps, together with its windows, its slenderness , furthermore highlighted by the sharp steeples of the same style as the one imposed by the Hernán Ruiz’s since the Giralda.

Cathedral. Jerez de la Frontera (Cádiz).

It is then when the city begins to appear, that Jerez of the Illustration which in the 18th century invented its wines and started to build houses with new styles imitating the splendour of the ancient classic world. Main streets show façades with elegant balconies; to their back, ones with wisterias and bougainvilleas hanging on their walls, like winks to the wayfarer who travels along the secrets gardens of the enclosed yards and cellars. Surely there will be no other city with more enclosed gardens for many than this, with exotic plants and trees, for the love for exoticism reached such a level that someone could afford the luxury of including ponds for alligators in them.

For centuries, vintner families built their warehouses for their industry as if they were monasteries: swaths of barrels in cathedrals provided with vestries for the unhurried tasting of wine.

According to the popular sayings, it was there, in the small plain that stretches before the descent to the oldest part of Grazalema, where the toro de cuerda had its origin. This is a popular corrida (bullfight) that took place in every wedding party and on certain days and became so popular that its scenes are engraved in the choir stalls of the cathedral of Seville. Although it has declined in many places, still today it is a distinctive feature here in Palm Sunday and, however strange, in Arcos de la Frontera too. Someday, the influence of the manors in the personality of the villages should be studied.

The Cabildo Viejo or Old City Hall in the neighbourhood of San Dionisio. It was declared an asset of cultural interest in 1943.

The hamlet begins to stir in the heat of the morning among tiles proclaiming wines and brandies in their façades and on the counters of their bars; bottles and cups in others are signs for dance academies… these are the synergies that flood the city from the Cuatro Caminos (Four Roads) to the Povera, where a road to Seville starts and opens to the area of other big properties, those which were brought on by the 1800s, golden and turbulent, bountiful and dramatic.

One of them, the Palacio de las Cadenas (Palace of Chains), hosts the Real Escuela de Arte Ecuestre (Royal School of Equestrian Art) which relates Jerez to Vienna. It is said that the house was designed by Garnier ̶ he of the Parisian opera ̶ for a family native to France who alternated between times of splendour and ruin until the unavoidable apportionment and sale to those who were economically ascendant.

Headquarters of the Foundation Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art.

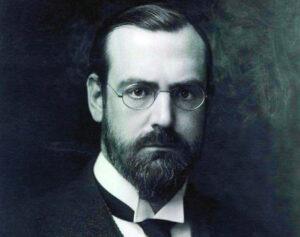

Here lived Walter B. Back, and his friendship brought here Abel Chapman to write together The unexplored Spain; Milton A. Huntington, the founder of the Spanish Society of America was also around.

American philantropist Milton A. Huntington was captivated by Spain after reading George Borrows’s works The Zincali and The Bible in Spain. The year was 1882 and he was then a young heir only twelve years old. But from that moment on, the idea of travelling to Spain kept on pursuing him until 1892, when, coinciding with the celebration of the Fourth Centenary of the Discovery of America, he arrived, according to his words, to “the most fascinating country in the world.”

American philantropist Milton A. Huntington was captivated by Spain after reading George Borrows’s works The Zincali and The Bible in Spain. The year was 1882 and he was then a young heir only twelve years old. But from that moment on, the idea of travelling to Spain kept on pursuing him until 1892, when, coinciding with the celebration of the Fourth Centenary of the Discovery of America, he arrived, according to his words, to “the most fascinating country in the world.”

His biographers state that it was the work El Cid by 17th century French playwright Pierre Corneille that powerfully drew his attention towards Seville through the love that El Campeador felt for the city. Huntington sponsored the equestrian statues of El Cid Campeador in Seville (a twin of the one that presides over the main entrance of the American Society of America in Nueva York that later on was to join others dedicated to Boabdil and Don Quixote), and those in Washington, New York, San Francisco, San Diego or Los Angeles. In 1897, one of the first publications with which he starts his collection of facsimile editions is El Poema del Cid, which was followed by carefully prepared editions of the main works of Hispanism like LaAraucana, Tirant lo Blanc, Artús de Algarve, El Quijote and many others.

Huntington took part in archaeological excavations such as that of Itálica (Seville) after having rented the plot, which enabled him to get in touch with very valuable sources to obtain materials to increase his collection of historic antiques, but above all the acquisition of large libraries.

The philantropic works reached other fields like painting, and he became the patron of quite a number of artists like Sorolla, Fortuny, López-Mezquita and Zuloaga.

With the accumulation of such a large collection, he founded in 1904 the Spanish Society of América with the expert advise of the greatest intellectuals of the time in Spain: Menéndez-Pelayo, the Duke de Alba, Miguel de Unamuno.., who at the same time connected with their American counterparts, including writers such as, among others, Mark Twain.

Apart from the magnificent Spanish library of old books (with more than 200,000 volumes from which 50 are uncunabula), and the valuable collection of the Spanish Golden Age paintings, the archaeological collection gathers more than one thousand artifacts ̶̶ some of them more than four thousand years old ̶ , the ceramic objects and the pieces of sumptuary art led to it being merited as the largest museum of Hispanic art outside our borders.

Equestrian sculputre of the Cid Campeador outsaide the Spanish Society of Amreica. New York.

Rolling on and on, this mansion and its gardens ended up being the headquarters of an institution which, in the hands of government, now serves as the ambassador of this city and of all Andalusia and Spain. Here is the horse who commands in a peaceful war aimed to open doors, conquer markets, and take the flavour of a millenary land anywhere. The riding arena, saddlery, the carriages arranged in its museum, horses neatly housed in their stables… everything has been put together in a process in which randomness and intuition, reason and feeling have merged.

Probably that is also how Jerez can be, too, a mixture of Cartesian ratiocination and equestrian cabriole.

By Antonio Zoido

Writer