Napoleon’s encyclopedia, the richest museum in the world

“Paris has the weight of a lead cloak to me! Your Europe is a molehill! Only in the East, where six hundred million of souls live, can be found great empires and to undertaking great revolutions!”.

Napoleon Bonaparte, the victor in Italy, languished after the peace of Campoformio with Austria in October 1787.

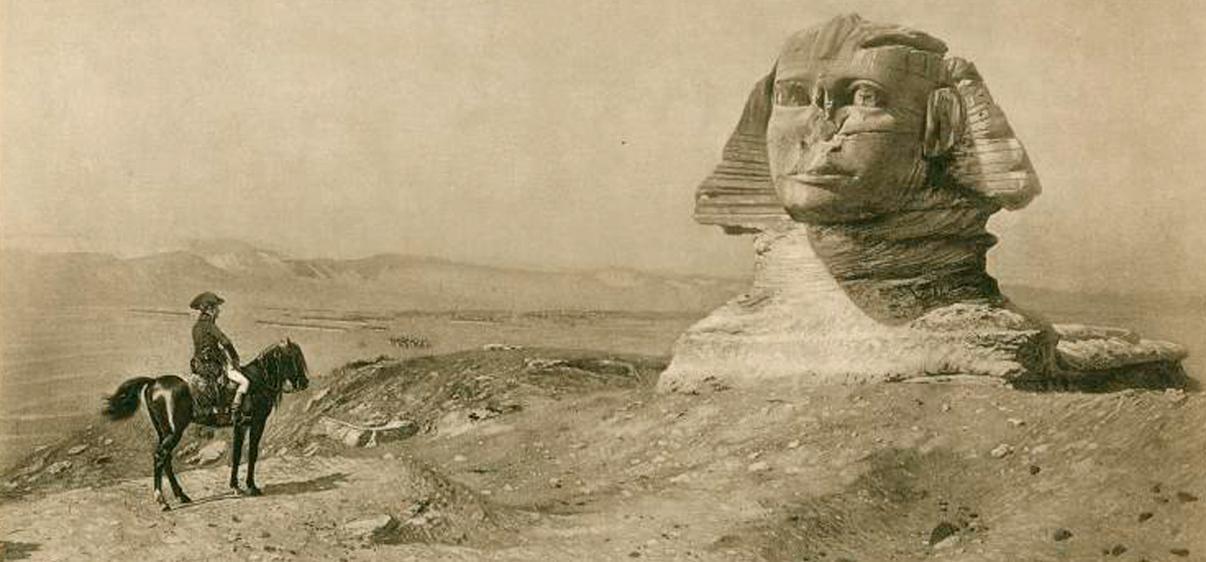

Cartoon published in the press of the period showing Napoleon in the Egyptian campaign.

The France of the Directorate was free from continental wars, although it kept its dispute with Great Britain. The government, maybe wanting his young and ambitious military genius be doomed to failure in an impossible mission, entrusted Napoleon to plan the invasion of England, but the Corsican general, after months of meditation, scrapped de project for he considered it too dangerous.

And while he was building plans in the air to invade the British islands, consumed by ambition, and always dreaming of accomplishing the feats of Alexander the Great and his immortal glory, he started to think of Egypt. Was not in Egypt where the Macedonian had started his fantastic journey towards India? ¿Was not there, in the oasis of Siwas, where he had dreamt of his grandiose destiny and where he was adopted, according to tradition, by the old god of the Pharaonic Egypt?

Egypt became Napoleon’s obsession, that slight, restless general 28 years old, who bored to death in Paris, longing for action and the glory of the battle fields and willing to find the ideal setting to beat the English.

Politically, as his brothers advised to him, it might also be an appropriate operation: the oportunity to reach laurels, to become a must to France ̶ despite India was not reached ̶ while in Paris the government suffered erosion. Egypt had everything: it was an easier expedition than that of England; it was about the realization of a dream of glory and, politically, it was opportune to disappear from France and not getting burnt out because of the Directorate. And the Directorate also agreed with the great oriental dream of the active military man:in Egypt he will stop being a hassle. Foreign Affairs Minister Talleyrand found the operation plausible, for the East had always been linked to France, at least during the time of the Crusades: Godfrey of Bouillon, Saint Louis, the Franks kingdoms. It would be a popular operation. Moreover, the territories that could be conquered there ̶ without having to fight directly with England ̶ would compensate for the French losses; the expedition could even bring fine trade and economic links, and it went beyond the usual colonial goals located in America or Asia.

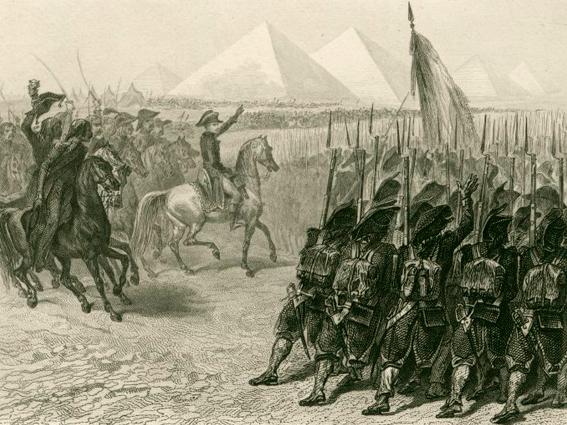

Propaganda drawing of the Battle of the Pyramids, with Napoleon before his troops.

“Egypt, placed by Nature so close to us, offers its huge advantage to stablish commercial relations, either with India or with more distant places… Egypt is by no means Turkey, which had no authority there…” wrote the minister Talleyerand.

That popularity was not alien to the wave of Orientalism that travelled Europe from mid-18th century, fueled by the winds of Enlightenment, which impacted it directly. A decade earlier he had read the History of the Arabs, by François Augier de Marigny, and Memoirs on the Turks and the Tartars, by the Baron de Tott, and he even tried his luck in the pen when he was twenty, writing a tale of Arab atmosphere. His passion for the matters of the East, and particularly for Egypt, is obvious for many of his biographers, to the extent that they found Egyptians complexes in him. Napoleon hoped to “accomplish great feats”. In words of Henry Laurens, and according to the mentality of the young Corsican: “that was the land of the great conquerors and lawmakers, and Bonaparte represented the entrepreneurial spirit of Revolution. He thought that, rather than in Europe, it was in the East where everything could be transformed, everything could be invented.” Even more, he had read recently the article “Egypt” in L’Encyclopédie and there he found above all a challenge: “Before, it was a country to be admired and now it is a country to be studied.”

Hence, the expedition to Egypt became the panacea that was convenient to everybody. That is why Napoleon could have everything he wished to be carried there: 36.000 men, one hundred canons, 600 horses, a massive reserve of arms and munitions and a sum of millions for expenses; besides, he was provided with 180 transportation means, which were guarded by 13 ships of line and fifty frigates, corvettes and patrol boats. While his generals ̶ Berthier, Duroc, Marmont, Bessieres, Murat, Dumas… ̶ inspected and urged the preparations, the Corsican paid all his attention in putting into operation an even more delicate task than the military one.

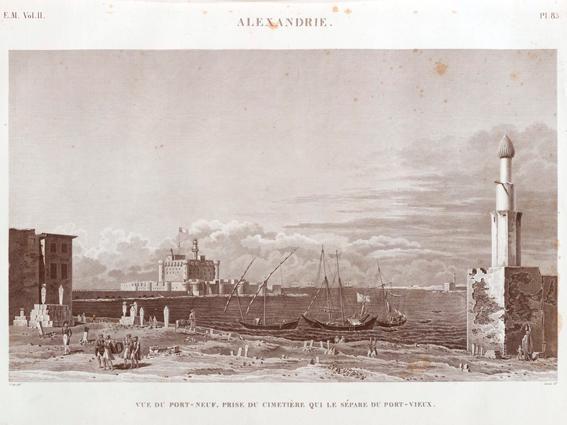

Port of Alexandria.

Teaching and learning

Napoleon took with him to Egypt a library and a librarian to whom he recommended not providing novels to his generals but history books: “Offer history books to them. Men should not have other readings.” For that young man was a passionate reader of history and he knew very well the facts and ideas of the great men from the past. One of his favorites was Pericles, the Athenian leader who never lost sight of the fact that one of the higher aims of Athens was its civilizing mission. Napoleon pointed out that Athenians did never have a great empire and, however, their prevalence in the first pages of History was far higher than that of other military powers of the time, like Sparta or Macedonia. He had no doubt that that was due to the expansion of their culture, whereby he was prepared to pull together Alexander the Great’s military genius and Pericles’s political talent.

For that purpose, he selected a large scientific team that should develop a doble function in Egypt: helping natives to improve and learning from the old Egyptian civilization as much as they could. It was not an improvised work, nor a secondary one. The Directory, making their own the instructions that the very Napoleon had drafted, ordered him, among other missions, to use “every means to improve the lot of Egypt natives.” With that double mission, Napoleon invited more than two hundred illustrious personalities belonging to the fields of science, art, and literature, to take part in it. He finally succeeded to join him 167 specialists, among them first prominent scientists like Dolomieu, Saint-Hilaire, Conté, Monge; writers like Villoteau or Parseval-Grandmaison; artists like Redouté and Vivant Denon; journalists and printers like Tallien.

Cartoon published in the press of the period showing Napoleon in the Egyptian campaign.

On July the 1st 1798, the French expedition reached the vicinity of Alexandria. Three weeks later, Napoleon defeated the Mamluks, sent by Murad Bey, in the battle of the pyramids, taking possession of Cairo the 24th. The defeat of his fleet in Abukir, on August the 1st, did not break his determination to stay in order to accomplish his mission, and Egypt became the headquarters of his projection towards India. Hence, while his generals defeated a great part of the Mamluks who left eastbound, in the battle of Salahieh, in the Sinai, Desaix was in chase of another three thousand Mamluks, sent by Murad Bey himself, who was trying to reach shelter in Upper Egypt. And while all this was happening, Napoleon was ready to rule: setting up a diwan or council of illustrious Egyptians to reach a collaboration, ordering the mathematician Gaspar Monge to found the Institute of Egypt; to Tallien to initiate his printing presses to publish a newspaper in Arabic: to Denon to accompany Desaix to Upper Egypt to draw everything, to doctor Larrey to study “ophthalmia”, that so much torment the Egyptians and that soon would affect the French. Everyone, each with their own expertise, started to exert the mission of teaching and learning, what Napoleon so much wanted, and in which he himself took part, as well as in the works undertaken by the general of engineers, Caffarelli, sharing with him the inspections ̶ and some dangerous adventure ̶ of the old pharaonic canal that linked the Mediterranean and the red Sea. Research and measurements, continued by Le Père, was the starting point for the building of the Suez Canal.

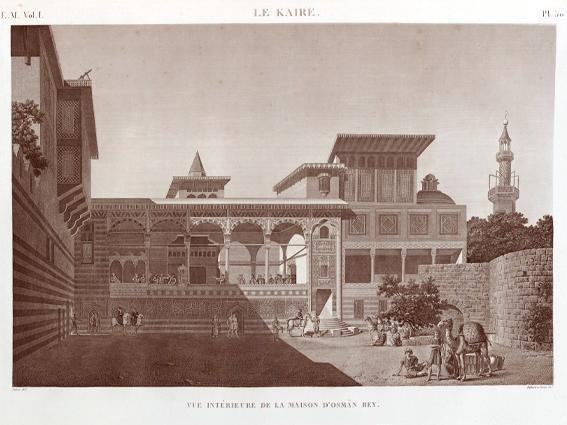

Interior of Osman Bey’s home.

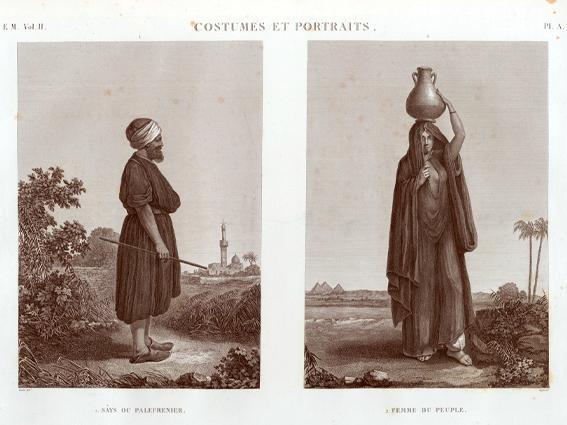

Images of a groom (left) and a countrywoman.

Egyptian historian Abd al-Rahman al-Gabarti, a contemporary of Napoleon’s presence in Egypt, left an accurate chronicle of the time in his story of the wonderful monuments extracted from biographies and annals. The historian underlines the French obvious politics of presenting themselves as friends, even as co-religionists, so as to allay fears and suspicion, using the policy of the “carrot and the stick”, complementing and benefit ordinary folk and menace and punish those who join or help the Mamluks.

The expedition members started to settle in the rich emirs’ mansions and the Mamluks who escaped, were expelled or dead. Napoleon occupied Muhammad Bey al-Alphi’s palace, in the elegant neighbourhood of al-Azbakiyya, by the shores of the lake of the same name, just built and furnished “as if the owner had prepared it for the general Bonaparte”. Other adjacent mansions were occupied by the chefs and officials, while the troops had theirs in the vicinity of the banks of Nile River.

Soldiers melt with the population: they went to the markets to buy bread, meat, chicken, eggs, sugar, tobacco… etc., paying even more than what vendors asked, in a studied policy of becoming popular. That boosted agricultural and crafts production. The new settlers immediately started to impose a series of city regulations in the European style: the obligation to provide light to roads, sooks, shops and, even, the façades of houses; sweeping, watering, and cleaning the streets.

French engineers made up the city in the banks of the Nile and islets: they undertook works in the Nilometer and in al-Rawda Island, they demolished houses and a few mosques, they reduced a little hill, demolished bridges that were useless, restoring an old one and building a new one; they cleaned up the wetlands and transformed them in orchards and gardens; they widened roads as that connecting al-Azbakiyya square with the Bulaq neighbourhood (current 23 of July Avenue, one of the most important roads in Cairo nowadays).

Al-Gabarti’s chronicle points out that workers were not subdued to free or forced personal allowance, but, on the contrary, they were well paid: they could return to their houses by noon, and they were provided with machines that facilitated work, being taught to operate, and even building them.

This idyll was relatively short. Isolated from France, Napoleon only had Egypt to go ahead with his mission, and hence he had to be sustained with the taxes that he collected in the country. The situation worsened after his failure in the campaign of Palestine, with the loss of many men and equipment that had to be replaced. There were riots and repressions that would aggravate once Bonaparte returned to France in 1799. Confrontation between occupants and occupiers culminated with the murder of general Kléber himself in Jun 1800. By then, everything had been degraded and the scientific activity was perhaps the only one in continuing its mission.

The scientific task

In the collective memory and the history of culture hardly anything has remained from the confrontations of invaders from both sides. The greatest memory is the transcendence of the scientific mission that accompanied the Napoleonic army. In al-Nasiriyya neighbourhood (today al-Munira), located at the foot of the Tall al-Agrab hill, which they had fortified, invaders kept one of their streets and its houses for the use of French scientists. In Mamluk emir Hasan Kasif Garkas’ old residence, they established a big library managed by an archivist who was aided by some assistants, whose task was to providing books to “the students who gathered there every day, two hours before noon. They were placed in the yard next to the library, sat in comfortable seats arranged in parallel to a wide and elongated board.”

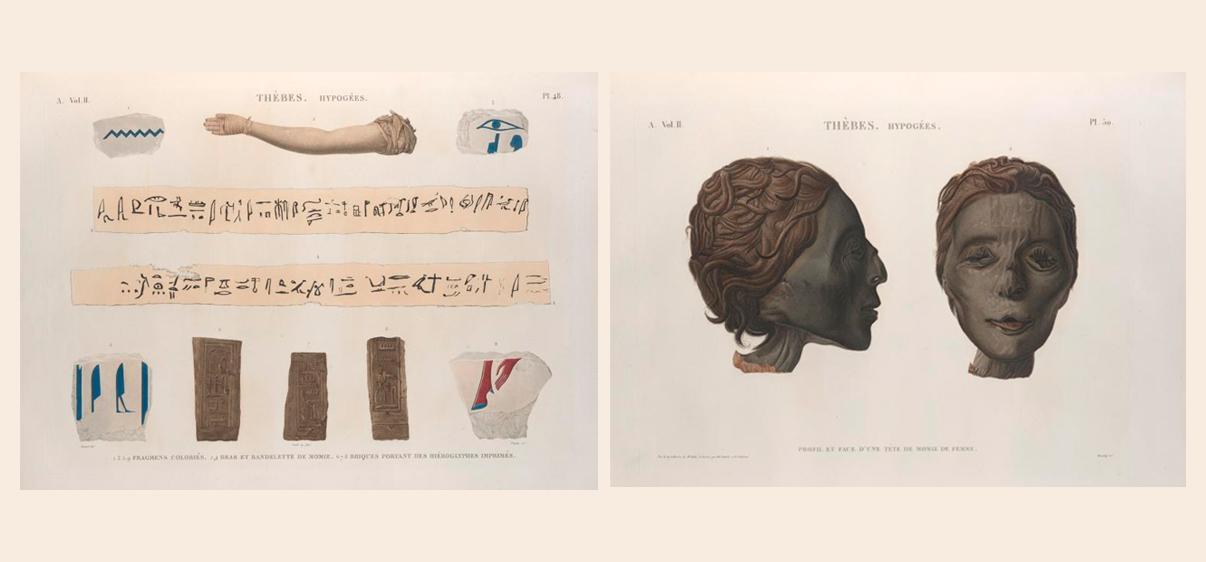

From left to right. Diverse studies performed on findings of one of the hypogea in Thebes. Mummies found in a hypogeum in Thebes.

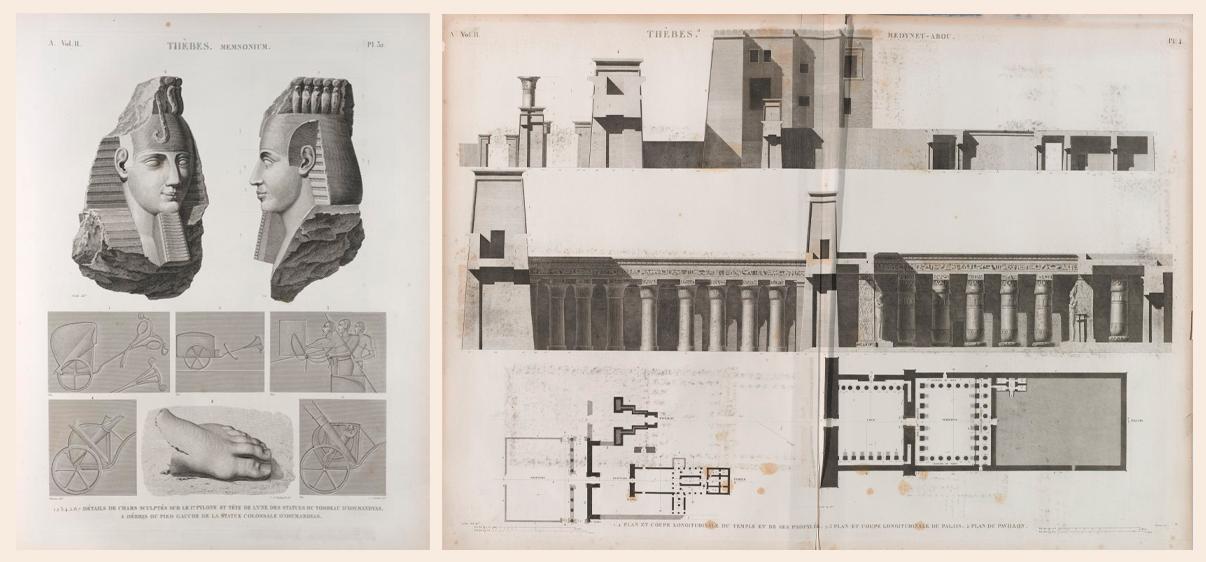

Below, from left to right. Details of the studies performed on the different artifacts found in the temple of Ramesses II (Ozymandias after the Greek version of the name). Plan and longitudinal cut of the temple of Madinat Abou, Thebes, with its Propylaea. Plan and longitudinal cut of the palace, and plan of the pavilion.

Anyone who wanted to learn could come in, from soldiers to as many Egyptians wished to observe or participate. Natives were kindly welcome, particularly when they showed curiosity and were keen to pose questions. All kinds of printed and illustrated books on any theme were shown to them: regional geography, flora, fauna, history of the ancient ones and history of the prophets, with their sayings and miracles. Al-Gabarti himself was there several times and, among the many books he could see, he was amazed by an illustrated story on Muhammad, with illustrations of the prophet, the Orthodox and the major imams, containing also sheets with the images of the holy places of Mecca and Medina, as well as rare Arab manuscripts. He also saw illustrations of the pyramids and the topography of the deserts in Upper Egipt, and he was specially surprised by grammar books in other languages that “helped in the task of translation in any language different to his own at the same time”.

Next to the library, they placed an astronomical observatory which drew the attention of visitors: it was equipped with “machines composed of small pieces which, once assembled, took up a lot of space, and that once they were used, they were kept in small cases”. And the same enclosure was shared by drawers, “Erigo represented man as if he was going to speak”; next to him, other colleagues drew and represented animals and insects, birds, and fishes and, when any of them was unknown, they “put them into jars with a liquid that kept their body immutable.”

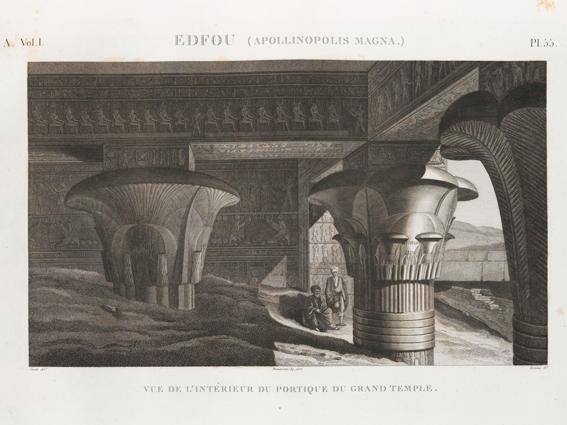

Inside the porch of a temple.

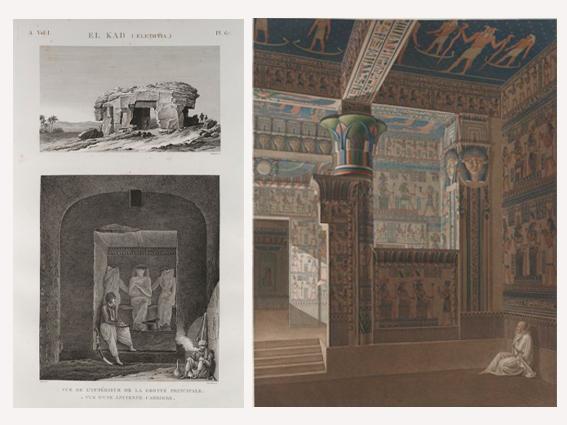

Outside view of a grotto (above) and inside an old quarrel (below). On the rigth, Tebas, perspective view of the coloured western temple.

At the Mamluk noble man Dhu l-Fuqqar Katkhuda’s home, worked the engineers who produced small precision devices and, in a corner, doctor Roya was installed, “where he had his ointments pastes and his diverse small bottles”, according to al-Gabarti; on the other hand, at Hasan Kashif Garkas’ home (one of his houses was used as library, as it has been recorded) chemists and physicians were busy. The historian was admired of the work done in the laboratories, that is the way he underlines that chemists melted liquids that send out smoke of colours and left yellow, blue, or red small stones in the bottom of the recipient, and some of these blends burst by approaching a flame.

Carpenters made furniture, chariots, carts, sheaves and lifting machines used in construction; smiths worked in big plants set by themselves in whose roof they installed, according to al-Gabarti, “big vacuum that aired with a slight movement.”

This was the way the French worked in Egypt, where they collected, prepared, and tested what would be an important legacy for the universal culture. They surprised Egyptian with these activities, opening them their eyes to an unknown civilization that filled them with admiration.

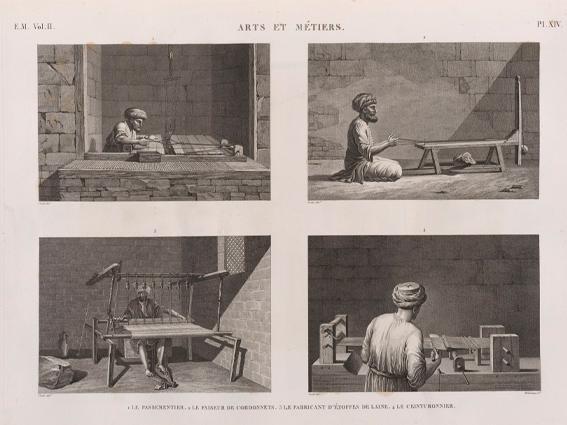

Crafters in a cordage workshop.

The starting point of the “Resurgence” of Egyptian literature ̶ and Arabic in general ̶ took place in parallel to the years the French were in Egyptian soil. The value attributed to the French expedition in this revival of Arab old literature is very diverse. On the one hand, conventional, classical criticism ̶ European and Arab ̶ considers that the French expedition had a fundamental role because he provided several elements that were the basis to that awakening: the installation of two machines for the first time in Arab soil, used to print newspapers, booklets and manifestos in French,, Arabic, Turkish; the arrival of theatre and opera groups to entertain soldiers and, above all, the scientific approach extended to the native population.

More nationalist criticism argues on the contrary that the only value to be attributed to the French expedition is that its presence in Egypt caused that an Otoman army was sent to expell them from there; as a chief of those troops arrived Muhammad Ali, who in 1805 took power. To this current of thought, Muhammad Ali might have been the true architect of this resurgence of literature since, in fact, the expeditionary troops returned to France along with their scientists, prints, books and knowledge.

It could not be denied, however, that the French expedition represented to the Egyptian society of the 18th century a ray of light that enabled them to glimpse a sample of the most advanced society of their time, that was worth to imitate.

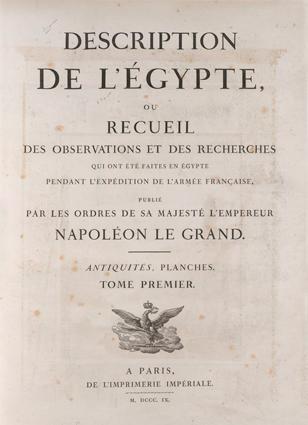

Inside cover of the Description de l’Égypte.

Learning from a wonderful civilization

Little had remained in the memory of the scientific part if the French had not thought from the beginning to materialise in a great encyclopedia every research, observation, and findings. In order to make progress in the works, establishing clear criteria, unifying mapping and names, placing the findings… they created, under Kléber’s Government, the Commission of Information on the State of contemporary Egypt, where hundred people, including some Arabs, worked for a year and a half in the ten subjects that were fundamental to know the country:

- Administration: property, heritage, taxes, and public expense…

- Police: Rules of operation.

- Government: Public offices, external relations, and recent history of the region.

- Army: recruitment, training, and equipment.

- Commerce and Industry.

- Agriculture: Crops, rural economy, irrigation methods, medicine, and vet in the countryside.

- Natural and human history: The nature of the soil, astronomical observation, ages and way of life of the Egyptians, diseases, medical knowledge.

- Monuments and traditions: mosques, madrasas (Koranic schools) water sources, aqueducts… houses and private palaces, typical dresses, furniture scenes of everyday life.

- Geography and hydraulics: cultivated and irrigated lands, nature of crops, river navigation…

This commission, together with the compilation of works of natural history, archaeology, cartography, and the artists’ drawings, established the foundations of the future Description de l’Egypte, a true encyclopedia of the collective understanding, treasured by the scientific expedition.

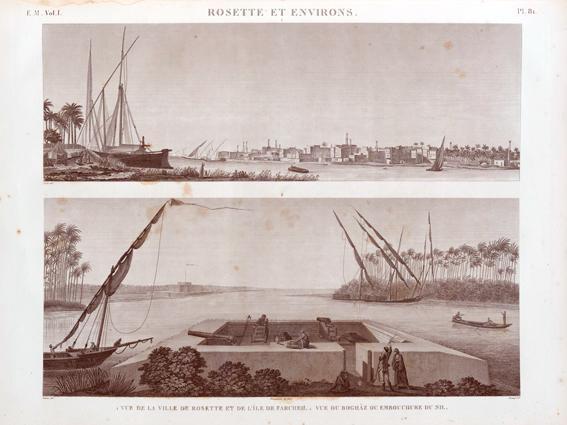

Everybody concluded their field surveys in the year 1801. British troops defeated General Menou, successor to Kléber, in Abukir in March, and despite he tried to keep a stubborn resistance, he had to surrender in Alexandria on 30 August. In the surrender agreement, Menou had to accept, among other clauses, the ceding to the victors of the small museum with artifacts from Pharaonic period that he collected only by gathering the antique remnants that were on the surface: 27 statues, ̶ partially fragmented ̶ several mummies and sarcophagi and a big stele in black basalt, written in three languages, which was found in Rosetta by the deminers while they were doing fortification works.

The artifacts were sent to England, where King George II donated to the British Museum. This was the start of the Egyptian collections but in any case, the Rosetta Stone, despite being one of the great treasures of the London Museum, will always remain inextricably linked to France, for it was not only discovered by a French man, but it was also another French, Champollion, who deciphered the hieroglyphics on the basis of the clues that thar stone provided.

After being defeated, Frenchmen were repatriated, but the dossiers of their scientists, writers and artists were plenty of treasures. Among them, Baron Dominique Vivant Denon is worth to be mentioned for the huge enterprise that this multifaceted man undertook, whose literary and artistic works achieved excellence. To him, who followed for six months the army in the campaign of general Desaix, we owe the hundreds of wonderful drawings that made Egyptology greatly popular. Among them, there are some monuments that are the only witness of buildings that disappeared shortly afterwards, like Amenhotep III’s chapel in Elephantine, the temple of Montu in Armant, that of Contralatopolis, beside Esna, or the one built by Alexander the Great in Hermopolis Magna, in Faiyum.

Port and surroundings of the city of Rosetta.

That treasure would have reached an unlimited dimension if every specialist had published his experiences separately. Yet, the intentions of private publishing were aborted by the leaders of the expedition. General Mesnou had already recalled this to the members of the scientific expedition in the service of the Republic, paid by it and organized within a military expedition. Napoleon had maintained the same criteria when they all returned to France and, by the start of 1802, he organized the Commission of Egypt, whose aim was to compile and organize the materials. That commission was managed in turn by Conté, Lancret and Jomard, with the collaboration of almost all the members of the expedition from which the works of some 120 works were selected, starting to appear in 1809, in volumes of wide format ̶ around a square metre ̶ under the title Description de l’Égypte, (Description of Egypt) or Recueil des Observations et des recherches qui ont été faites in Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’armée française, publié par les ordres de sa majesté l’empereur Napoléon le Grand. (Account of the observations and research that have taken place in Egypt during the expedition of the French army, published under the command of the Emperor Napoleon the Great.)

The contents of that first expedition, the last volume of which appeared in 1822, is in general lines the one listed by the Commission of Information, with the addition/which included the archaeological works, the studies of natural history and the formidable collection of engravings resulting from the artistic team, with those by Vivant Denon high on the list. These engravings, compiled in 11 volumes, meant the main key for the success of the work: 900 illustrations from life in wide format ̶ essentially archaeological and artistic material as well as contemporary architecture, archaeology, customs, trades and traditions ̶, the printing of which was possible thanks to the collaboration for many years of around 300 engravers and drafters. The main proof of such a success was that in 1821, the great editor Panckoucke started to publish a second edition, this time a more commercial one and in streamlined format. In its prologue it can be read: “The title might have been Encyclopédie de L’Egypte , as it shows the history, monuments and productions; no country has such a complete description of all its parts and it is not probable that a similar series of circumstances, nor the will to produce such an ensemble of works like these and to erect that amount of monuments”

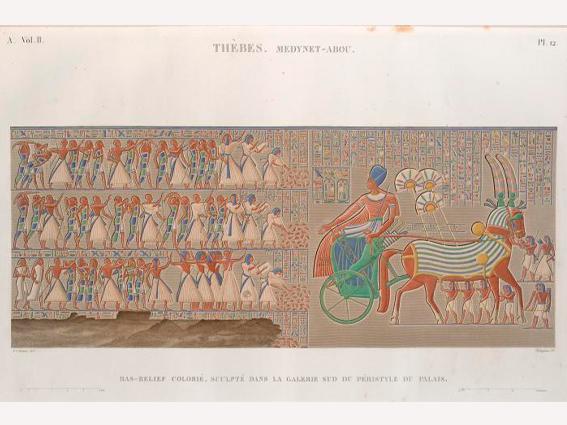

Multicoloured relief, carved in the south peristyle gallery in the palace of Madinat Abou, Thebes.

In the historic foreword, Jean Baptiste-Joseph Fourier, ̶ Secretary of the Egyptian Institute ̶ made clear that in this work learned men were moving within a cultural and historic territory so innovative and attractive. Those pioneers of Orientalism and Egyptology foresaw that they were operating in a complex field of relationships East-West, and from North to South, and between memory and present time.

Jean Baptiste-Joseph Fourier writes:

“Located between Africa and Asia, easily connected to Europe, Egypt occupies the centre of the old continent. This country has great memories; it is the homeland of arts, and it preserves countless monuments, its main temples and the palaces that inhabited its kings still survive despite its lesser old building had been already built before the Trojan war. Homer, Lycurgus, Solon, Pythagoras, and Plato went to Egypt to study sciences, religion, and law. Alexander founded a city there, an opulent city which dominated commerce for a long time and witnessed the decisions taken by Pompey, Caesar, Marcus Aurelius, and Augustus on the destiny of Rome and the rest of the whole world. It is normal, therefore, that this country attracted the attention of the illustrious princes that determined the future of the nations”.

“It has not been any other country in the East or Asia that had turned its eyes to Egypt and had not seen it, in any way, as their own natural territory.” And of course, France and Napoleon had reserved to conquering, showing and disseminating such a emporium of historic, and artistic wealth… In this way, the failure of the military campaign would be sublimated by the scientific project. Napoleon had opened the door to Orientalism and the Description of l’Égypte proofed his triumph.

Soha Abboud-Haggar.

Professor at the Complutense University of Madrid.

(Texts extracted from the Arab chronicle by al-Jabarti have been translated by the author of this article)