From the al-Andalus that still survives

“By the middle of the last century (referring to the 19th century), a German historian pondered the fascination that in its time was produced by the mere mention of Granada, remarking that even those who had not visited it yet, kept memories of the Alhambra.”

El moro de Granada en la literatura. Soledad Carrasco Urgoiti.

Research focused on the legacy of al-Andalus in Spain has increased over the last years. There are and always will be discrepancies about particular facts of the story of our country, for the perspective of a good interpretation must be always broad and varied. However, all researchers agree on one thing, that al-Andalus left indelible marks on our lives.Still today, six centuries after the last Andalusi left, we keep the habits and customs, speak a language containing numerous words of Arabic origin and enjoy an environment that resulted from the influence of al-Andalus. We should ask ourselves why, of all the cultures that lived here and changed our previous customs, was it al-Andalus that most endured. Christians, re-conquerors that came immediately after, failed to deny the obvious influence of al-Andalus, for they were nurtured by it in many ways. Maybe this is due to the fact that the Andalusi people never disappeared completely, and many remained first as Moriscos and later hidden under other names.

There are three possible contexts where Spanish citizen recognizes himself Andalusi: the physical environment (landscape and urbanism), domestic atmosphere (clothing, meals, hygiene, leisure) and the social environment (language and the collective imaginary). Let’s shift then from the universal to the particular, acknowledging each one of the gifts given to us by a single culture.

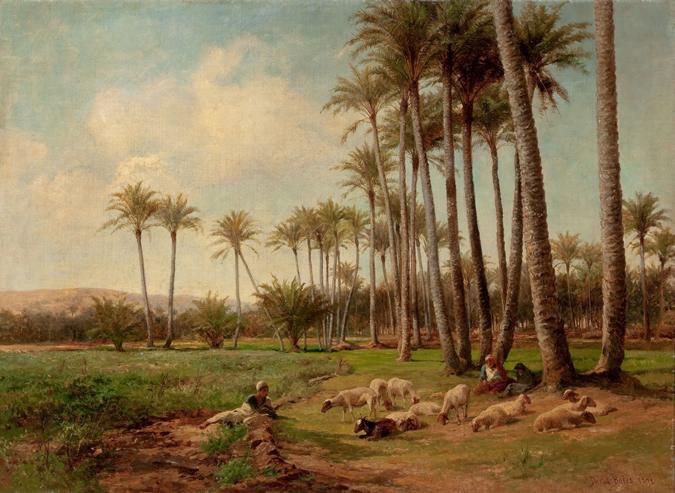

It is hard to imagine a Spain without palm trees. But it was so. Romans focused their commercial efforts on agriculture, on its three most classic aspects: cereals, olive trees and vineyards.

Physical environment

Most of the seeds that gave rise to new crops came from unknown farmers. However, there are records of more formal methods for their introduction. Abd-er-Rahman I was personally in charge of some species, among them the date palm.[1].

e can imagine how Spain was in the peak of the splendour of al-Andalus, covered with palm trees, for their remains still survive and, even though diminished, these woods are an undeniable part of our landscape. Elche and its huge palm tree grove, the largest in Europe, and one of the widest even among the Arab countries, shows how the Umayyads got this plant cultivation right. It is not a tree, although it can reach the dimensions of any of them. Maybe because it was not actually a tree, and could not be used as wood, was the fact that enabled the palm tree to resist destruction.

Others being proper trees, mostly fruit trees, repopulated the Spanish fields. So much so that someone has called this Andalusi revolution a “green revolution” that today continues to nurture us daily and has made of Spain one of the most forested countries. In this respect, the work of the American academic Thomas Glick (University of Boston) is worthy of attention.

[1] (Thomas F. Glick. Cristianos y musulmanes en la España medieval. 711-1250).

Watering system is still in use in most of the Spanish fields.

Such a rich landscape in arable land needed a hydraulic infrastructure. People of the desert who crossed the Strait of Gibraltar achieved their transportation of water through their experience in building qanats (underground irrigation channels based on a slope to conduct water) and the Roman aqueducts that they reused and enlarged. They invented devices to carry water and manipulated them to leverage its kinetic force.

In the case of the qanats, they became a practical tool for centuries. The most outstanding ones were those of the Sierra de Guadarrama (in the middle of the Iberian Peninsula), which conducted the water to the city under the so-called name of “viajes de agua”, a technique that ceased to be used from 1858 on, when the Channel of Isabel II was inaugurated. Not surprisingly, the very name of Madrid, that is to say Mayrit, means in a generic sense: “sites where tunnels for water collection are abundant”, as the Arabist and historian Juan Vernet points out.

The waterwheel (noria in Spanish and na’ura in Arabic), and the water channels (acequias in Spanish and saqiya in Arabic) are still used for watering Spanish fields. To the left, the famous Rueda de Alcantarilla (Murcia), built in the 15th century. Above Molino de San Antonio in Córdoba.

Orchards in Eastern Spain and in most of the central areas of Castile keep on using this system that is so easy and, in addition, effective. It is the same with the cisterns in the city of Granada, that today are still preserved virtually unchanged, on the hill of the Albayzin quarter.

Each and every one of these advances were already regulated in ancient times, as we can clearly see in the Ordinance of Water in Granada in the 16th century. That tradition has reached our days in the Tribunal de las Aguas de Valencia, (court to make law about the use of water) or in the wide range of Irrigation Communities that join forces to make of this product of the land a collective good.

The Spanish landscape contains myriads of visible traces from al-Andalus; not only those given by nature, but also the man-made ones.

Fortress of La Mota and the abbey church of Santa María la Mayor in Alcalá la Real (Jaén)

Castles, so abundant in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula, come from the coexistence, sometimes belligerent and others not so much, with Christians. Between razzias (revolts) and cavalry raids, the Spanish landscape was transformed. The same applies along the coastal zones with watchtowers and fortresses, and these expand our vocabulary with military terms where the Arab influence was particularly noticeable: alcázar, alcazaba, (citadel) almirante (admiral), are clear examples of the interrelation between Christians and Andalusi inhabitants. Defensive walls and pigeon lofts start to appear, which show the strategic level reached during war and the interest they showed in communicating.

In urban centers al-Andalus supplied more of its character. Since the first armies crossed the Strait until the last of the Nasrids left, in Spain were forged splendid unparalleled cities. In the 10th century, Córdoba had 300,000 inhabitants and its streets were lit and paved. We should not forget that Paris or London were not so, even nine centuries later.

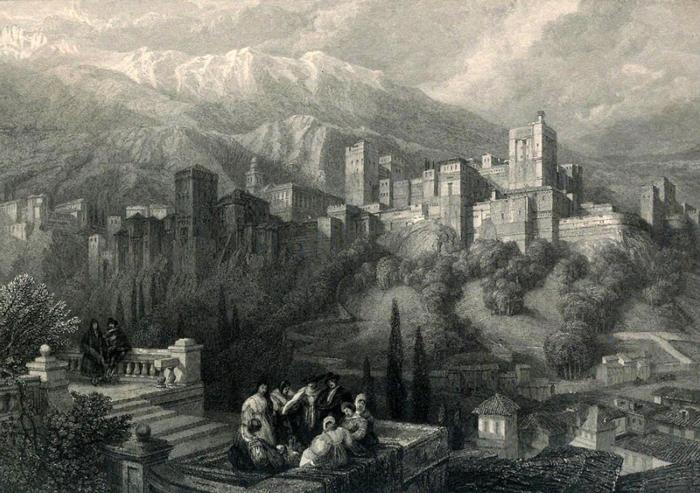

The Andalusi civilization’s legacy can be recognized in every city they have gone through. Narrow streets with whitewashed houses or with mullioned windows through which women could watch without being seen. Most Cordoban streets or those in the Albayzin in Granada, Malaga’s historic centre and a myriad of towns in Andalusia are a microcosm of al-Andalus. Granada, as it is the most “Moorish” city of the whole Iberian Peninsula and with the most centuries of Muslim culture, has the most recognizable Arab houses.

Not in vain, architect Leopoldo Torres Balbás in his work “Ajimeces”, gives an insightful review regarding these overhanging that protrude in façades in Granada’s homes that exist in parallel with those in cities like Cairo or Marrakesh. Equally interesting are the observations that this master of architecture makes regarding the souks, public squares and shops that still exist in our towns and that are heirs of al-Andalus. Suffice it to recall, despite having been restored after the fire in 1843, the layout of the Alcaicería (ancient souk) in Granada. The restoration effort, in a historic moment when everything was demolished to construct simplistic buildings after the concept of Modernism in the 19th century, can only meet with the interest for keeping the forms and uses of our historic awareness.

Also, it is so with the cármenes (typical houses with gardens and orchards in the quarter of the Albayzin) so much in line with the Andalusi tradition, connected with the effort made by the first Muslims, who so much loved the idea of paradise on earth.

The interweaving of Granada’s streets has produced unique circumstances like those dead-end small squares, or those singular cobertizos (roofed constructions which link two buildings separated from each other). To the left the Cobertizo de Santa Inés and to the right the one located at Gloria Street, both in the immediate vicinity of Carrera del Darro.

Domestic environment

If landscape and urban layout are the direct heritage of our Andalusi past, no less so are the customs that have shaped our idiosyncrasy. From the very moment we get up every morning, in our alcove (from the Arabic al-qubbah), having slept on an “almohada” (pillow, in Arabic al-muhadda), we start an existence that is fundamentally Andalusi. When we bathe, a habit that not even Christians managed to avoid despite being considered by Alphonso X the Wise a facet of “idleness and effeminacy”, we cover with an “albornoz” (bathrobe; al-burnus).

Coming back to the Oriental spirit, al-Andalus promoted pleasure of the senses. Cleanliness, essential for Muslims, was annexed to beauty and delight. A name that no Spaniard should ignore is that of Ziryab, a Persian based in Córdoba in Abd-er-Rahman II’s court, who changed each and every of our social customs. He invented the toothpaste (whose components are still unknown) and an effective deodorant. Ziryab has been considered the Petronius of Oriental customs. If we think that fashion is a current invention, we are wrong. Ziryab introduced innovations like the haircut in men; he prescribed the shaving of the beard and introduced a custom that has lasted until today:

“From June to September people must dress in white, with which (Ziryab) revolutionized customs, since until then it was a colour reserved for mourning, who from that moment on should dress in black in the warm months to be distinguished from the others.

In October, white clothes should be abandoned to be substituted by apparels in relatively dark colours of raw silk, brocade, and wool, over which they wore furs or pelisses in winter.

Finally, in spring people must wear brilliant colours and wear silk sheer dresses, if possible.”

Ziryab, mindful of the Cordoban tastes introduced one of the most international board games: chess.

This clarification, included in the work Arabs’ daily life in medieval Europe by Charles-Emmanuel Dufourcq, confirms to us that Ziryab has been the most influential person in our daily life. Choosing colours depending on the calendar months or dressing in mourning are not unknown customs today. We should not forget in this section on dress, that it was the Andalusi people who introduced in Spain the exploitation of cotton and the culture of silk. The first, whose word in Arabic is qutun, was from India, but even though it was known since old times, it did not achieve a large-scale development until the Arabs introduced its cultivation in Andalusia, then passing to Italy and France (12th c.) Flanders (13th c.), Germany (14th c.) and England (15th c.) as explains the already mentioned Vernet.

An interesting circumstance is what occurred with the use of the veil, which was an essential element for the woman of high nobility, up to the 19th century.

We should not forget that it is still used by most brides in the wedding ceremony, and that it was indispensable until recently to pray inside a church. Other uses of it have been more worldly, but the expression of an Andalusi heritage, as it is the case of the so-called “veiled women from Mojácar” (Almería) who in the 20th century still wore it when they went to the fountain to collect water, and they held it with their teeth.

Ziryab’s influence did not end with the ways of dressing, nor in that of personal care. Cuisine was one of his greatest achievements. Mediterranean cuisine is the direct heir of the concerns of this princely man. He introduced in our country such common foods in our pantries today as asparagus, and what is to be said about one of our favourite dishes, meat balls (albóndigas in Spanish, bunduqah in Arabic).

Inés Elexpuru, in her popular book entitled La cocina en al-Andalus, (The Kitchen in al-Andalus), does not ignore either that among all edibles provided by the Andalusi orchard is rice. Paella is the direct inheritance from this Oriental crop which knew well how to exploit it. Also it is so with sugar that sweetens the majority of our coffees, a beverage from Africa introduced in Spain by the Andalusi civilization. Coffee, whose bush it is known to have stimulated camels, has become fundamental in our daily life. The Andalusi people, like modern Spanish, were coffee addicts. To a lesser extent, tea was always spiced and symbolized hospitality. Over the last few years, tea shops have sprung up, where the waterpipe, or hookah (shisha) is used, so ill-adapted to modern times.

The Andalusi people were fond of throwing parties. They even celebrated the festivals of Christians.

Poet, medicine doctor and vizir of sultan Yusuf I, Ibn al-Khatib said about the people of al-Andalus that they were white-skinned, black-haired and of medium height, a description overwhelmingly modern. Andalusi people married and celebrated weddings by accompanying the bride and the groom throughout the streets of their town, as it is still done in many places in Spain. And once the ceremony was over, people threw a rain of rice over the heads of the newly-weds, which in the East means abundance.

We know that they were fans of bullfights, not exactly in the Christians’ way, but they organized shows with bulls, and in the maritime areas they organized boat races, which Juan Vernet considers having inspired modern regattas.

We do not know if in these events the Andalusi people used rockets or fireworks, for gunpowder was also introduced by the Arabs after one of their many travels to China. Its use was of course dedicated only to war, but it has remained firmly anchored in Spanish people, showing its maximum expression in the Fallas Valencianas[1].

[1].The Fallas Valencianas is a annual traditional celebration in commemoration of Saint Joseph that last five days with a pyrotechnic spectacle of firecracker detonations and fireworks. The most popular event is the burning of the Fallas (monuments made in burnable materials) the last day.

Staging a scene of daily life at the Aljibe (reservoir) de San Cristobal.

Social environment

Every culture is consolidated by language. In Spain, we cannot deny the legacy of al-Andalus that is reflected in our dictionary. Namely, we have more than four thousand words from the Arabic language.“German invasions of the Iberian Peninsula, says Arabist Rachel Arié, hardly left any traces in the Spanish vocabulary. The heritage of the Visigoths’ is limited to some 90 words, not one of them related to the world of nature or agriculture, which positively shows their lack of penetration into life in the countryside”.

The linguistic Arab influences can be seen clearly according to crafts, like bricklayer (albañil in Spanish) builder (alarife) potter (alfarero); legal terms like mayor (alcalde), sheriff (alguacil); rural terms like arroba (custom unit of weight) the fanega (Spanish bushel); related to watering: waterwheel (noria), aljibe (cistern); related to agriculture: orange, apricot (albaricoque), lemon, artichoke (alcachofa).

Other terms commonly used have an unknown etymology, as it is the case of the word ojalá, whose origin is supposed to be that of the Arab expression “in shaa Allah”, or when God wills. It is also the case of the word algarabía (hullabaloo), whose origin was the name that Christians gave to the Arab language (clearly noisy), that ended up meaning fuss, or uproar.

Many idioms also preserve the Andalusi imprint, like “de higos a brevas” (“once in a blue moon”), “No hay moros en la costa”, (lit, “there are no Moors along the coast”), “Esto o es moro o es cristiano”, (This is either Moor or Christian) or the compliment ”You know your house is here”, which we stress when we offer our home to a stranger, a characteristic expression of Islamic hospitality that seems to have remained in our collective memory.

In Granada, where the linguistic legacy is more evident, the so-called imala is noteworthy: it is a matter of replacing the “a” long-vowel sound by the long “i”, as reflected in words like Bâb ar-Ramla (“Gate of the Sand”) by Bîb ar-Ramla. These connotations bring us closer to the Andalusi in a more human and realistic way, and in the same way we can distinguish the different accents of the Spanish provinces, which in Granada stands out with its open sound of its vowels.

The introduction of paper in the Iberian Peninsula was also due to al-Andalus. From all the travels to the East, it would be paper that was the faster element most rapidly adopted universally. The Andalusi people always acted as the point of union with the rest of the world, as on so many occasions, by providing the most useful channel for science and literature. On it were put and will be put the diversity of words they gave us, which will also be transmitted electronically, as for instance e-mails, associated to the Andalusi term of @, arroba in Spanish.

By requesting some of the most outstanding Arabists and Andalusi culture researchers about the validity of the Arab customs in Spain, we find Manuela Marin’s reflection related to the collective imaginary of the Andalusi past. In our days, there is a pressing need to trigger the cultural memory of our past. Over the centuries, we have witnessed performances of “Moros y Cristianos” (Moors and Christians) until evolving into a static festival.

Celebration of the Moros y Cristianos (Moors and Christians) Festival in El Campello (Alicante)

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in times of the Second Spanish Republic appeared institutions like the School of Arab Studies of Madrid and Granada, which have been caretaking our historic memory, a remembrance that literature has embodied in our days in multitude of books. Historical novel reached us through Romanticism and today it enjoys its peak moment.

María Soledad Carrasco Urgoiti (may she rest in peace†) in her essential book El moro de Granada en la literatura (The Moor from Granada in literature) starts by saying: “By the mid-XIX century, a German historian weighed the fascination that in its time was produced by the mere mention of Granada, remarking that even those who had not visited it yet, kept memories of the Alhambra.” The author quoted this in the fifties of the 20th century.

Before she did it, the very popular writer Manuel Fernández y González made his profits telling Moorish stories. Later, writers like Antonio Gala or Magdalena Lasala would jog our memory with works clearly based on the description of Granada and Córdoba when they both were Muslims.

For whatever reason we do not know, which in a given moment will be object of study by sociologists or even philosophers, in Spain was born a feeling of appreciation of al-Andalus that expands toward the universal. That is to say, we do not need just to keep alive the idea of a reality that existed in a particular time, that of al-Andalus, but as Carrasco Urgoiti said, it is already an idea associated to our uniqueness, one we cannot afford to ignore. The demystification of certain aspects of the Andalusi culture is also part of that cosmos recreated in our own time. It is well to extrapolate from al-Andalus not only its virtues, but also its mistakes. The Andalusi culture, ultimately Muslim, was also responsible of some gendered habits throughout the centuries, which either for convenience or by simple tradition, have been dragging on in Spain well into the 20th century.

May it be that this article is a reminder of the historians, sociologists or philosophers seeking to continue researching our past.

CAROLINA MOLINA is a journalist

and author of the novels

La luna sobre La Sabika (The moon over the Sabika) and Guardianes de la Alhambra. (The guardians of the Alhambra).