Umar ibn Hafsun and Bobastro

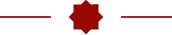

A character for a historic city

By Virgilio Martínez Enamorado. Professor at the University of Malaga

There are few people in history who have generated such a massive bibliography as Ibn Hafsun from the 19th century, due precisely to his eventful, hazardous life.

Umar ibn Hafsun (847-918), the “rebel” par excellence of al-Andalus (his revolt from Bobastro started in the year 880), played a significant role in the history of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule. His Hispanic origin, with a credible genealogy, his supposedly “aristocratic” station, his conversion to Christianity and his political actions, all led him to create a vast political domain. He came to control, directly or indirectly, more than a third of the territory of what is now Andalusia, by means of a series of alliances with diverse rebels, which has been used as an argument of a great importance in order to defend the continuity of the local facts that have taken place in the history of al-Andalus history up to, at least the Caliphate of Cordoba. These are the visions that have made of this persona sort of a Hispanic nobleman, representing certain social sectors with very different criteria regarding the imposition of “foreign” political pressure that Islam supposedly entailed. Since the Arabist from Málaga Francisco Javier Simonet drew up a first historical profile sharply detailed, these ideas have been repeatedly emphasised. That his rebellion was the result of a reaction of aristocratic local elites and the uprising of Christians. It is true indeed that in the 19th century that vision was seasoned with a deeply reactionary component, which mainly derived from his conversion to Christianity.

In the last century, more recent views tried to offer a more “modern” perspective of him, by updating him with a “social” reading: he would then become the last “lord of feudal income”[i], belonging to Visigoth nobility, a Hispano aristocrat who, in order to defend his possessions and privileged position, rose against the Umayyads in the 9th century.

[i] The feudal rent was the mechanism by means of which certain people or institutions of the nobility or the clergy obtained production surpluses from farmers in the feudal mode.

Contrary to the descriptions which reduce the character to a merely local or “Hispanic” element, with nothing whatsoever to do with the government under Islam ruled, Umar ibn Hafsun set forth a political programme aimed at trying to substitute a dynastic succession of the Umayyads. In order to get it, he used, on the one hand, a foreign relations policy towards most of the Muslim dynasties in the West or the Maghreb that coincide with him in time (Aglabids, Idrisids or Fatimids), and on the other, an apparently oscillating domestic policy defined by the need to create subjects for his dynastic project among a mainly Christian population. There is only one way to be able to understand the religious precepts he repeatedly cited: he shifted from an early attachment to the “official” Sunni Islam directly inherited from his progenitors to the Christianity of his oldest ancestors (989) to die probably as a Shiite (913), a debt he owed to the Fatimids who clearly supported him as an alternative to the Umayyads. In this sense, Bobastro, the basis of his revolt, must be understood as a dynastic city. In conclusion, his exercise of power clearly places him in the center of the Muslim political community, without arguments to make him part of neither a supposed feudalism nor of a prior political tradition of Visigoth roots.

The place of Bobastro, in the municipality of Ardales (Málaga), has hardly deserved attention on the part of archaeology, despite being one of the most recurring subjects for medieval Spanish historiography, due to its links with Umar ibn Hafsun’s famous revolt or fitna, which took place between the end of the 9th century and the first quarter of the next century. From the point of view of the valorisation of historic heritage, its potential is enormous, and there is no doubt that a project to recover the site for people’s access and enjoyment, for scientific knowledge would revalorise the historic monument and landscaping value of Bobastro.

The site is located in the so-called Mesas de Villaverde, one of the wildest and unique of Andalusian geography, some 37 miles away from the capital, in a north-westerly direction. The area, known as El Chorro, has an extraordinary archaeological interest. The site of Bobastro constitutes a natural bastion, a cliff practically inaccessible and surrounded by deep gorges, as described by Arab authors. Among them was al-Himyari, who relished its contemplation as none other:

[Bobastro] Bobastro is a solid fortress in al-Andalus, located eight miles far from Cordoba. It sits on the top of a rocky and isolated peak, so high that the eye cannot even see it, and whose access is terribly painful. It is provided with two gates; to get to the highest one, it is necessary to climb a trail which can be only used by pedestrian lightly loaded; both to go up or down, it is necessary to walk along the river course. The peak summit is formed by a rectangular platform from whose rocks spring fresh and running waters, which spill from there. Wells can be opened with no great effort. The castle of Bobastro was the Christians’ headquarters. It consisted of a great number of convents, churches and domed buildings. On it depended farmsteads and castles, and these are important. In its surroundings there are plenty of running waters, diverse scented woods, vineyards, fig and fruit trees, as well as olive trees. But now, in the region remain only a small part of what it had, due to the damages it had in the wake of Ibn Hafsun’s uprising. .

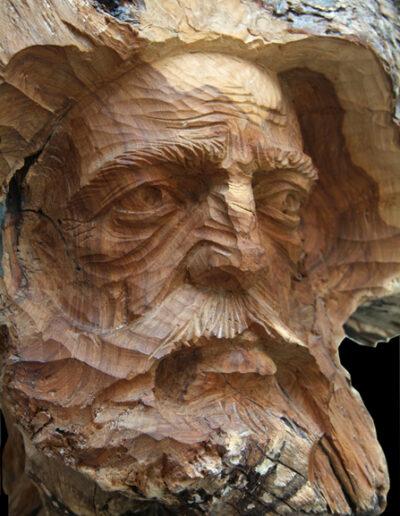

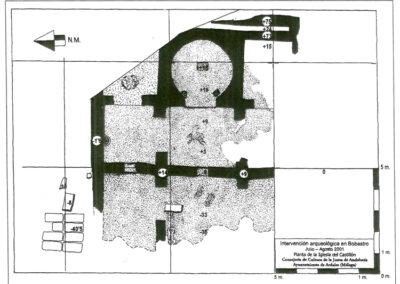

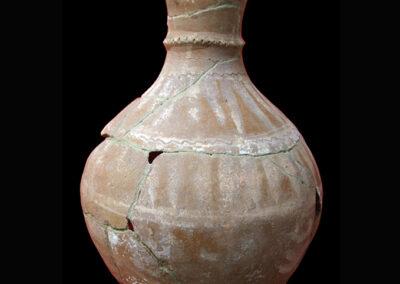

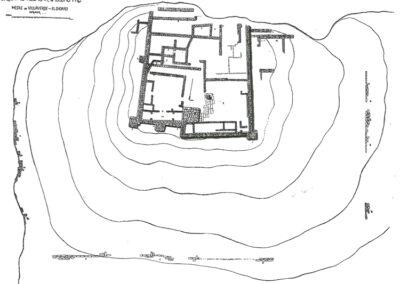

Las Mesas settlement has in total 60 hectares of great archaeological Interest. One of the elements that confers Bobastro its unmistakable signature is the proliferation of housing and cave buildings of diverse dimensions, some natural, and others readapted to be residential. Of all the preserved buildings, the most known is with no doubt the basilica of Las Mesas de Villaverde, widely reproduced in works and the epitome of the “Mozarabic” art in the south of al-Andalus. It is included in a true dayr o or fortified convent in the shape of a big square, surrounded by an outer wall to which several rectangular rooms are attached. In the centre of that squared space there is a sort of yard like a cloister where a cistern to collect water and a grain silo have been excavated, which popular imagination has wanted to turn into Ibn Hafsun’s tomb. Big storage jars have been found in one of the corridors. It also was provided with a small cemetery, which has not been excavated yet. The four-sided space is enclosed by still another wall which borders the access to the basilica, protecting the path leading from it to the citadel. Its chronology coincides with that of the fitna. On one of the sides of the ensemble that stands up to the Basilica, carved in the rock as a cave church following the eremite tradition of the Mesas de Villaverde and a symbol of Bobastro’s identity since the last century. With a typical basilica plan inscribed in a rectangle, with three naves, the central one being bigger, it presents a transept for presbyterial use with gates to delimit the naves and the apses. These alternate square plans (the two laterals) a with the circular one of the central nave, are where only strict religious ceremonies took place. The interior space is quite partitioned, and it offers a great hierarchy that takes advantage of the unevenness of the land from the apses to its feet. Underneath these, a beginning of a crypt was carved. But if this idea is suggestive, the evidence of these temples built by the rebel served as a model for other buildings, like that in the north of San Miguel de la Escalada (León), with which it shared a deep stylistic connection. The first references written in Arabic sources referring to Bobastro are, at least, from the year 903, while those for the first of northern Mozarab art, that of La Escalada, its building date, according to the foundation stone, was the year 914.

If this is the most representative construction in Bobastro, we must say that there are many other preserved in the so-called medina, or city, whereby means of an operational system consisting of terraced-built housing units −some above ground, and others subterranean− subjected to the great citadel, which was built as we can see it reconstructed today. These residential units are almost always half-cave structures of different sizes. There are two ensembles that stand out for their monumentality, the so-called Casa de la Reina Mora (House of the Moorish Queen) and the Cueva Encantada (Enchanted Cave). All that central sector is organized around the citadel, located in the highest point of the Mesas de Villadeverde, the hill of El Castillón, where Abd-er-Rahman III built “according to his plan”, in words of Ibn Hayyan, a massive urban fortress upon the foundations of a former one, once the fitna was over and shortly after the most part of the rebellious population came down to the plain.

Pieces and images of the archaeological site

Bracelet found in the metropolitan church during the archaeological mission in 2001.

Museum of Malaga.

Natural viewpoint at Tajo de la Encantada in Bobastro, where we can see the Pico de la Huma and El Chorro mountains.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Manuel ACIÉN ALMANSA, Entre el feudalismo y el Islam. ʻUmar ibn Ḥafṣūn en los historiadores, en las fuentes y en la historia , Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, 1994 (2ª ed. con prólogo, 1997).

- Cyrille AYLLET. Les Mozarabes. Christianisme, islamisation et arabisation en Péninsule Ibérique (IXe-XIIe siècle) , Bibliothèque de la Casa de Velázquez, 45, Madrid, 2010.

- Pedro CHALMETA, “Precisiones acerca de ʻUmar ibn Ḥafṣūn”, II Jornadas de Cultura Árabe e Islámica (1980), Madrid, 1985, pp.163-175.

- Maribel FIERRO, Abderramán III y el califato omeya de al-Andalus, Nerea, San Sebastián, 2011.

- Manuel GÓMEZ MORENO, Iglesias mozárabes. Arte español de los siglos IX al XI , Madrid, 1919.

- Virgilio Martínez Enamorado, Sobre Mergelina y Bobastro. Edición facsímil de la obra de Cayetano de Mergelina Bobastro con estudio crítico introductorio , Agrija Ediciones, Cádiz, 2003.

- Al-Andalus desde la periferia. La formación de una sociedad musulmana en tierras malagueñas (siglos VIII-X) , CEDMA, Málaga, 2003.

- “Sobre las ‘cuidadas iglesias’ de Ibn Ḥafṣūn. Estudio de la basílica hallada en la ciudad de Bobastro”, Madrider Mitteilungen 45 (2004), pp. 507-531.

- ‘Umar ibn Ḥafṣūn. De la rebeldía a la construcción de la Dawla. Estudios en torno al rebelde de al-Andalus (880-928) , Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica, 2011.

- “Bobastro (Mesas de Villaverde, Ardales, Málaga): nuevas aportaciones sobre la ‘base de los ‘aŷam’ del sur de al-Andalus”, en E. Cerrato Casado y D. Asensio García (coords.), Nasara, extranjeros en su tierra. Estudios sobre cultura mozárabe y catálogo de la exposición , Cabildo Catedral de Córdoba, Córdoba, 2018, pp. 77-93.

- La iglesia rupestre de Bobastro y la ciudad de Ibn Ḥafṣūn, Ardales Tur Ediciones, Ayuntamiento de Ardales/Diputación de Málaga/Consejería de Cultura de la Junta de Andalucía/Candidatura a Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO, Málaga, 2021.

- “‘Umar ibn Ḥafṣūn: paisaje con figura. De aprendiz de sastre a emir de Bobastro”, en G. Lora Serrano y Á. Solano Fernández-Sordo (eds.), Mozárabes en la España medieval. Cristianos entre al-Ándalus y los reinos cristianos [siglos VIII-XIII], Almuzara, Córdoba, 2022, pp. 299-315.

- Rafael PUERTAS TRICAS, Iglesias rupestres de Málaga, CEDMA, Málaga, 2006.