Daily Life

in al-Andalus

The life of a country is not measured only by its artistic and scientific achievements, but above all, by delving into everyday life, customs, social structures and organization. In this field, al-Andalus was also advanced and cultured. It created a new type of very structured urban society and at the same time, work in the fields was revolutionized vitalizing agriculture, providing new methods of cultivation and a large number of new agricultural species.

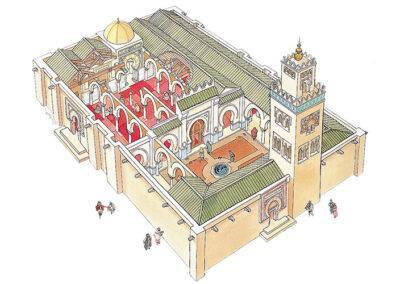

The urban nucleus was the medina, with a close and dense design that in turn, was organized in two zones: commercial and living areas. The souk was a meeting place, above all masculine, where, in the midst of frenzied movements, the most diverse transactions took place. Trades and stands were placed according to specialized areas where the most varied merchandise was to be found: from spices to scents and vegetables and fruit, meat and textiles, silverware and ceramics. A strict set of rules controlled trading –rules that can still be found in Ibn Abdun‘s or al-Saqati’s complete treatises on hisba –whose honesty, not always guaranteed, was closely watched by the almotacén, inspector of weights and measures. Al-Andalus established a solid administration and· a somewhat complicated judicial system. Purchases were made in cash, which came primarily from the mint at Cordoba and from other towns in the Taifa period. Dinars, dirhems and feluses were legal tender.

The mosque was also a place that was frequented not only by community prayers, but also by different types of social and neighbourhood meetings, or simply to study in quiet surroundings, or to escape from the heat of summer amidst the forest of columns. Domestic life was carried on outside the trading area, in the medina’s fortified quarters which, for greater security, was closed at night by means of two doors. The homes were austere and sober outside, but could be most luxurious inside and were, in any case, a refuge of peace and comfort, far greater than was usual in other parts of Europe at the time. They were all built round a courtyard –where, if allowed by the family’s finances, there would also be a small pool or, at least, a well– the bedrooms, sitting-rooms and kitchen all opened onto the courtyard and they were also placed round the upstairs gallery. Furnishing was simple: chests, low inlaid tables, and niches in which to place a book or perhaps an ivory ornament. For the sake of comfort, matting and thick wool carpets were often placed on the floor, along with soft silk or wool cushions and a good brazier.

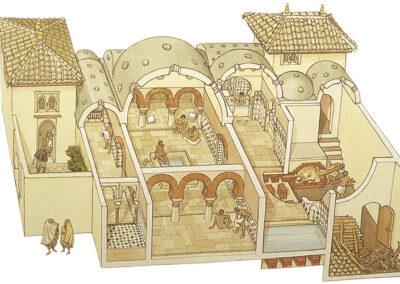

Each home had a room for personal washing and was equipped with a drainage network, as well as lighting systems, which is considered quite sophisticated for the period (9th and 10th centuries).

There were many public baths. In Cordoba alone, under the caliphs, there was a time when there were more than 600, according to sources. Customers not only got washed in them, they also relaxed and allowed themselves to be energetically massaged. In some of them, the afternoon was set aside for the women, which was also a time to chat, do themselves up, and even enjoy sweets. Depilatory paste, henna, aromatic oils, musk and jasmine fragrance, clayey soap for the hair, antimony for outlining the eyes (kohol), bark of nut to colour the lips and gums …, were part of a true cosmetic arsenal of the Andalusi woman.

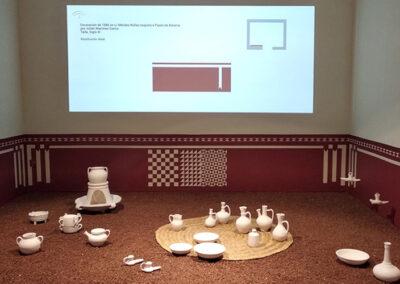

In the kitchen, women exerted themselves to make delicious dishes, such as a kind of almond macaroon (alfajores), honey covered pancakes (pestiños), meatballs with cumin, cuscus, a pie with peas and hake, fish with green coriander and stuffed aubergines.

Vegetable gardens in the times of al-Andalus flourished as never before, full of new vegetables like aubergines, artichokes, endives, asparagus…, and new fruit such as the pomegranate, melon, citron and apricots. Gardens were full of fragrant, colourful flowers: stock, rose, honeysuckle and jasmine. Irrigation ditches ran full and waterwheels were heavy with clear water.

Grafting techniques were improved and botanic gardens were created for medicinal purposes near hospitals.

Education, as mentioned before, was much appreciated by the Muslims, which they developed from an administrative point of view. The student could go to the mosque or to the madrasa to receive the education of his choice on condition, of course, that he was already proficient in the sacred books and theological sciences. If the family was well-off, a tutor would go to the pupil’s house for private lessons.

Prayer room in the Madrasa (Granada). It was the first University of Granada and was founded by Yusuf I in 1349.

Replica of part of andalusi kitchen furnishing: flasks, long-necked bottles, cups, large bowls and a washbasin.

History

Chronology

Art and Architecture

The Scientific and Cultural Legacy

Daily Life

Glossary