Antequera: art, history and culture

Between the Torcal Mountains and a vast fertile plain, along the Route of Washington Irving, lies the millennial city of Antequera. Cradle of illustrious characters, forerunner of the Renaissance in southern Spain, and a unique reference of the Andalusian Baroque, Antequera is, along with its breathtaking karstic topography that bears its name (the Torcal de Antequera) it is a true crucible of history, art, and landscape.

Spot at the Torcal of Antequera. ©Ayuntamiento de Antequera

If we divide the city into different itineraries, for which we recommend as a point of departure the bullring, which after having been built towards the mid-19th century and restored in the 1980s, can be considered as one of the most beautiful examples in Spain today.

Our first itinerary starts in the gardens adjacent to the Antequera bullring, where we can admire the monuments dedicated to the Sagrado Corazón (Sacred Heart) and the Sagrado Corazón de María (Sacred Heart of Mary). In the gardens that give shape to the so-called Paseo Real, the statue of Captain Moreno announces the monumental Gate of Estepa, a reconstruction of the former one that stood there up to 1931, in a style that could be named “Antequeran Baroque”.

From here, across a broad avenue, we can access Infante Street, the true urban artery of the city, where there are monuments of singular importance. In first place, the visit to the church of the patron, Nuestra Señora de los Remedios would be required. Belonging to a convent of the Third Order of Saint Francis in which after the Desamortización , the Town Hall was installed. It is today a parish church which preserves after its simple Mannerist front a lush interior, with its outstanding main altarpiece, a work of Churrigueresque style from the first third of the 18th century, as well as the Chapel of Nuestra Señora del Tránsito with a nave in an artistic Rococo style. The Baroque style that defines essentially both the church and the town hall, where the staircase and the monastery cloister are still preserved, promoted the ensemble to be catalogued as a Historical-Artistic Monument of National Interest.

At the beginning of this street is found what once was San Juan de Dios Hospital, a worked dated the end of the 17th century whose chapel has the characteristic Baroque style that in that century and later would be the architectonic and artistic reference for Antequera.

The Estepa Gate, a reconstruction of the original gate that was preserved until 1931. In a second plane, Plaza de Toros.

Continuing our tour by Infante Don Fernando, and among the many buildings that will attract the visitor’s attention, we find the façade of the former Casa de los Pardo (The Pardo’s House) Although there is nothing much to be appreciated in its interior, its façade is one of the main examples of Andalusian Mannerism, and the most beautiful artistic demonstration of this style in Antequera.

It is not the only example of civil architecture that keeps this city, as many are the palaces and bourgeois houses that spread almost everywhere in its historic quarter. Among them, in the same street we are in, is Bouduré’s House. This building of splendid ironwork in its gates and balconies was built in the early 20th century by architect Daniel Rubio. Its French eclectic style contrasts starkly with the sober neighbouring façade of stone masonry of the convent church of San Agustín. This temple, which belonged to the Order of the Saint of Hippo until the general dissolution of the religious orders in 1835, shows in its interior a wide major chapel of a great depth topped by a Gothic transept, to which the plaster works that it has today were added in the 17th century. On the exterior, framed between two buttresses, stands out its slim tower, which by its height and elegance could be considered the second most important one of the ample monumental collections of Antequera.

Infante Don Fernando street. ©Ayuntamiento de Antequera

The tallest bell tower in Antequera is based on the model of a Baroque tower whose unique physiognomy is due mainly to the fired-clay elements that decorate it, and the cherub of the wind vane, a symbol of the city and this square. Leaving behind the Renaissance fountain, designed by Pedro de Machuca in 1545, and the Arco del Nazareno (the Nazarene Arch), known under this name due to the humilladero that was on its upper part ̶, we begin the ascent to the higher part of Antequera.

Here, the breathtaking view of the city and its surroundings from the Mirador (Lookout) de las Almenillas surprises us, as well as the huge, monumental patrimony that the squares of Santa María and Los Escribanos contain.

First, giving access to the ensemble, we find the Arco de los Gigantes, (Arch of the Giants), a late-Renaissance construction founded on a Nasrid gate in 1585 by architect Francisco Azurriola. Although this arch has suffered significant dismemberments and losses by the passing of time ̶ among them the large statue of Hercules that crowned it within a niche ̶ still surprises us, both by its great height as well as by the Roman archaeological remains that the city council ordered to place in that site in the 14th century. From here, we can get into a wide garden area that recalls the placid corners of the Alhambra and the Generalife.

We are in the enclosure of the old citadel, whose walls could call to mind the times when the city was named Madinat Antaqira. In the visit to this monument, we need to recall the memory of Infante Don Ferdinand “the one from Antequera” who reconquered the city in the year 1410. Many ruins from this period and the subsequent ones remain, particularly in the Torre del Homenaje (Donjon). Here, apart from several spaces covered with interesting oblique vaults, there is a shrine in its upper part built in 1582 to host the clock known under the popular name of “Papabellotas” (bellota, the acorn, is the fruit the cork oak) because its construction was funded through the sale of cork oak plantation.

Royal Collegiate Church of Santa María

Going down again to Santa María Square, whose center is occupied by the monument dedicated to Pedro Espinosa, a work by José Manuel Patricio, we find the superb façade of the Real Colegiata, (Royal Collegiate Church) which gives its name to the square. The Colegiata was founded on 1514 by the bishop of Málaga, Don Diego Ramírez de Villaescusa, and it became home of a chair in Grammar and Latin Studies that was the origin of the Golden Age group of poets in Antequera to which Espinosa belonged. The works of this temple lasted more than three decades, and although they reveal some late-Baroque reminiscences, both in its design and in its decorative elements that already show the Renaissance style.

From the ensemble of this church, in whose construction many ashlars from the old Roman city of Singilia were used, its superb carved-stone façade is organized over three streets separated by large buttresses with three gates, the central one having a bigger dimension, and the two side ones correspond to their respective naves. These entrances, in the style of triumphal arches, represent both for their shape as for their decoration, classical examples of the Renaissance, in the same way that the blind balcony inserted over them do. However, there is no doubt that the most distinctive elements of the ensemble are the conical pinnacles that crown it.

The interior of the church, which is now used to host cultural events, is a beautiful columned basilical-shaped hall with three naves divided by large Ionic columns that support their corresponding rounded arches, all richly decorated. In order to achieve an increase in height, a body with discharging arches, as a sort of false blind triforium, was built. It is in the Capilla Mayor (Main Chapel), with deeper and wider dimensions, where the primitive Gothic design that originally decorated this church can be observed. This is shown in the ribbing of its vaults, which shapes stars of eight and six points. Nevertheless, the large Florentine windows, open to the side walls, reveal the turn that the building project suffered, that would be at last completed according to the Renaissance trends.

The front of this chapel was covered by a magnificent Baroque altarpiece which, as many other valuable artworks that once belonged to the Colegiata, are now missing or spread across the Museo Municipal (Municipal Museum) and some churches such as San Sebastian or San Pedro, where a canopy that belonged to the Colegiata is preserved. The rest of the temple’s chapels, some of them enclosed by interesting grilles, belong to different artistic periods, although as it happens in the vestry, it is the Renaissance-style ones that stand out. Both this space and the naves of the church are covered by Mudejar ceilings, which date back to the first half of the 16th century. The roof framework of the central nave is rectangular, while the side ones have octagonal shapes. Both are characterized by a superb latticework decoration formed by stars of different shapes.

Lastly, in the Real Colegiata de Santa María la Mayor, we can admire in situ the way people were buried in Antequera before cemeteries were created. This is throughout an old crypt accessed by a narrow step ladder in one of the chapels. After having been conveniently restored, it can be visited nowadays.

Los Herradores (The Farriers) Street

Back again in the Arch of Giants, we keep on walking through Los Herradores (The Farriers Street), until we get to Portichuelo Square, where the Virgin del Socorro’s chapel-tribune is, whose architectonic layout repeats itself in other religious constructions in the city. From this little square, the steps of Santa María la Vieja offers us a beautiful view that includes the nearby convent that once belonged to the Third Order of Franciscans. Its church, dedicated to Saint Mary of Jesus, suffered serious damage during the invasion of Napoleonic troops, and it had to be reconstructed almost entirely. Inside it is worshipped one of the most venerated images by Antequera’s natives, Nuestra Señora del Socorro Coronada, especially relevant during Holy Week. After this visit, we descend the street called Cuesta Real until we find the church of San Juan Bautista, a superb Renaissance temple that in the same way that Santa María and San Pedro is part of the style known in the city as “column churches”. In addition to the Mudejar celing that overs its naves, deserving of special attention are both the main altar, and the Capilla de las Ánimas, where the Cristo de la Salud is worshipped. Not far from this temple is the Virgen de la Espera hermitage, located inside the tower which opens the Puerta (Gateway) de Málaga, one of the old accesses to the city. This gateway, declared a Monument of Historical-Artistic National Interest, constitutes an interesting sample of Muslim civil architecture.

This monumental value is also shared with the former church-convent of the Discalced Carmelites, which is also close to the place where we are now. Its sober appeareance vividly contrasts with the exhuberance shown by its three grandious altarpieces in the main chapel. The one dedicated to the Virgen del Carmen is one of the most outstanding examples of Spanish Baroque, since, excepting the Mudejar tracery of its celing, that is more reminiscent of earlier periods, reflects purely the artistic canons of the 18th century.

Retracing our steps, we cannot fail to visit the church which once was the convent of the Order of Preachers. A work dated either in the 17th or 18th centuries, its central nave is roofed by an interesting Mudejar ceiling, and also outstanding are the superbe Baroque camarin (side chapel) of the Chapel of el Rosario and the main altarpiece with the image of Nuestra Señora de la Paz Coronada, one of the most popular in the processions of Holy Week.

To continue a second tourist visit to the city, the best would be to regain strength in one of the many restaurants which will delight us with their many typical dishes. No doubt they will offer us the porra antequerana , as popular as the classic charcuterie and chanfaina eaten for breakfast together with the traditional molletes with olive oil, or as the renowned variety of confectionery made in the convents, which is mainly composed of alfajores, pastelillos de gloria, angelorum, bienmesabe, or figs with nuts. All these delicacies will please the most demanding palates in the early afternoon.

Once ready to keep on discovering the monumental wealth of Antequera, we will start again by the church of San Sebastian in whose back is located the convent of the Discalced Carmelites, whose church of the Encarnación is another of the most striking Baroque works in Antequera.

After this, we will head towards Coso Viejo (old bullring) Square where the Municipal Museum is, hosted in one of the most important buildings of civil 18th-century architecture.

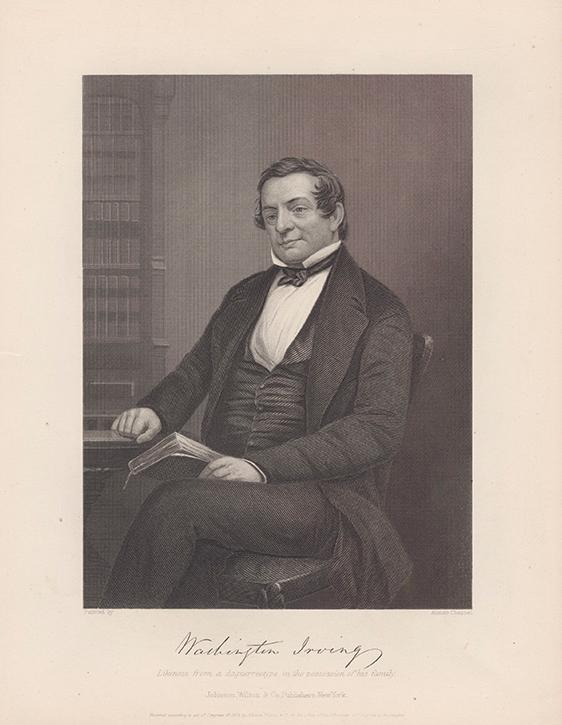

Walks through the Antequera of Washington Irving

In 1928, during one of the travels that took the writer from New York to Andalusia, he wrote about Antequera:

“We spot Antequera, the old city of warrior fame, located at the foot of the great mountain range that crosses Andalusia. Before it, a beautiful, fertile countryside expands, framed by rocky mountains. We cross a quiet river, and we approach the city through a place crowded with hedgerows and gardens, where nightingales intone their songs of evening.”

His stay in this city from Málaga made a powerful impression on the reputed author of the Tales of the Alhambra, fascinated as he was by the history, landscape and customs of the people from Andalusia, which were to serve as inspiration to him.

On his way to Seville, he stopped to sleep in the city, fearing the worst given the bad name that inns had in those former times. But on the contrary, his stay in Antequera made an excellent impression on him; he was particularly impressed by the good food, which still makes Antequera a leader in Andalusian gastronomy, with its famed specialties.

The Walks in Washington Irving’s Antequera, organized by the Foundation El legado andalusí, follow the marked route around the places that were to meet the eyes of the prominent visitor: its streets competing among themselves in terms of monumental grandeur, the surrounding landscape which by the differences of heights always provides new views, artistic styles all gathered in the city from which he gave the following account:

“I particularly like Antequera, located on the slope of rugged mountains with a fertile plain like Granada. Half a league away rises the steep crest that bears the romantic name of “The Lover’s Peak.”

After this, we will head towards Coso Viejo (old bullring) Square where the Municipal Museum is, hosted in one of the most important buildings of civil 18th-century architecture.

Noble architecture

The palace of Nájera is important not only due to its own architecture and outstanding lookout, but also because it is used to host the most important artistic collections in Andalusia. Among the many pieces exhibited there, there is the Ephebos of Antequera, a bronze-sculpture of great value which could be dated around the 1st century of our era.

Next to the museum, in the same urban space known in times of old as Plaza de las Verduras (Vegetables Square), we find the convent of the Dominican Sisters. Popularly known as the convent of Las Catalinas, its church was built according to the plan by Andrés Burgueño between 1724 and 1735.

Not far from the Descalzas square lies what once was the convent of the Minim Friars. They are under the patronage of Nuestra Señora de la Victoria, and was built in the first third of the 18th century. What strikes us from both religious buildings is the Palace of the Marquises of la Peña, built by the end of the 16th century after the styles of its time. Later on, as we continue down this road, we head towards the nearby convent of Santa Eufemia or that of the Minims, as it is also known. Its church has particularly interesting works, but the most characteristic element of this temple is without doubt the dome that roofs its main chapel. In Santiago Square we find the church of the same name, whose unique main façade is articulated as a two-story atrium.

Antonio Zoido. Writer.