Ibn al Shaykh of Malaga dazzled by the

Lighthouse of Alexandria

PART II

By María Jesús Viguera Molins.

Arabist. Member of the Royal Academy of History.

The Lighthouse of Alexandría, the Seventh Wonder of the Ancient World, was widely described by Arab authors. Among them, Ibn al-Shaykh of Malaga produced one of the most accurate of all.

The Lighthouses of Cadiz and Alexandria: why was Ibn al-Shaykh so interested in that of Alexandria?

Among all the Arab sources dealing with the Lighthouse of Alexandria, those included in the curious encyclopaedia titled , The Alphabet (Kitab alif ba), the work of our Malaga-born character stands out immediately due to their breadth and detail. When he travelled to Alexandria he toured with a great tenacity the very famous lighthouse, the manarat Iskandariyya, during some months in 1165 and 1166.

As we have already pointed out, the people from al-Andalus admired, used and reused the remains of antiquity, and sometimes they demolished them. And one of the most famous destructions was the Lighthouse of Cadiz (manarat Qadis). This demolition took place in 1145, precisely twenty years before Ibn al-Shaykh visited and scrutinised the Lighthouse of Alexandria.

Left, an engraving dated in the 19th century, shows the lighthouse that once stood in the bay of Cadiz. Right, an image of the Castle of San Sebastian, in the same site, where the new lighthouse stands nowadys.

There are several Andalusi descriptions of the Lighthouse of Cádiz, above all an important one from that same 12th century, which according to the geographer from Granada, Abi Bakar al-Zuhri (who was still alive in 1152) after transmitting the information from someone who saw it with his very eyes and recalled it as it was before it disappeared: “a large construction spread over three floors, triangle-shaped in the third one, topped by the statue of a man looking eastward, as if looking out across the sea to meet the gaze of the far more famous, six-meter statue of Poseidon leaning on his trident atop the Alexandria lighthouse. But in 1145, Maymun, the admiral of the Almoravid fleet, ordered its destruction, as it is said he thought that a treasure was enclosed in its calcareous stones (kaddan). The Almoravid empire collapsed shortly after, and sources written by their successors, the Almohads, did not hide their disdain at such an useless demolition.

In 1165, as Ibn al-Shaykh was taking such a great interest in the Alexandria lighthouse, was he perhaps thinking of the one that his countrymen had lost? Was he also making the case for the conservation and protection of Alexandria’s, and was he implicitly criticizing the Almoravids for having demolished it, which resulted in supporting the power of the Almohads, who happily replaced them? It is very likely that Ibn al-Shaykh, in going into such a detailed description of the Lighthouse of Alexandria, wanted to compare it with the information and ruins that remained of the Lighthouse of Cadiz.

In my opinion, Ibn al-Shaykh’s dazzle before the Lighthouse of Alexandria, is due to what he kept in mind about the memory of the recent destruction of the Lighthouse of Cadiz, and also ̶ as we have already mentioned ̶ he was in charge of developing constructions in his home town of Málaga. Thus, we can deduce, although we cannot foresee his specific objectives, that the benefits of having well-built construction would not leave him indifferent. There is something more than a mere curious drive and true professional care that led him to measure and describe the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Ibn al-Shaykh may be a special model of attentive traveller, but his behaviour is understandable.

Ibn al-Shaykh’s data before the Lighthouse of Alexandria

Ibn al-Shaykh, in his encyclopaedia The Alphabet (Kitab alif ba) goes through the Lighthouse of Alexandria and describes every inch of it, adding accurate details of the building. Let’s say again that Ibn al-Shaykh’s description is one of the most complete known, appearing on pages 537-538 of the old edition of his book from Cairo, accurately translated by Asín Palacios in the aforementioned article “A new description of the Lighthouse of Alexandria”, from which we will offer some excerpts next:

Ibn al-Shaykh begins by locating its accesses: “Between the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the city there is a distance of nearly a mile or more. The city is located to the south of the Lighthouse. This is placed on a small island amidst water, and from here, a road above the water has been built to reach the shore, whose length is 600 cubits or more, its width 20 cubits and its height above sea level 3 cubits. Therefore, when the tide is high, water covers this walkway… The Lighthouse rises at the far end of the island.”

The base was formed by a square that measured 45 steps on each side: “Sea waters lashed often the platform that surrounds the building on its east and south sides, which is on the rocks, under water… This wall is built very steadily, as if it was made of only one piece due to the tight junctures of the limestone stones (kaddan)…”. The inscription is found on the white stones of the southern wall facing the sea… with only the figures of letters, carved in hard stone, long and black… “A platform or pathway, 100 steps long [on] an arched vault similar to a brigde” leads to the door, raising fom the ground.

After entering, Ibn al-Shaykh described and counts the doors and rooms he found, until he heads up a ramp that turned to the gallery of the first floor. He attentively noted the dimensions he was able to measure: “for I wrote down all this on-site, since I went to the Lighthouse with the inkwell, and paper, and marked cord, so as not to lose even the smallest detail, for the Lighthouse is a wonder”. He described the shapes of the tower’s three tiers: at the base, square; in the middle, an octagon; at the top, a cylinder. He remarks that on top was a small mosque (masjid): “to which four doors give entrance to it, as if it were a dome.” He added that a fire was lit there was a wood fire on this upper part in order to guide boats into the harbor.

Ibn al-Shaykh counted the Ligthouse 68 rooms , as well as its total height: 53 fathoms, plus almost seven fathoms of foundations. Ibn al-Shaykh’s specific description of the Lighthouse is quite considerable, given the details about it, and the well-trained eyes with which he addressed it and the sincerity of his gaze, and as he does, he also expresses his doubts. Our Málaga-born traveller saw it fifteen centuries after its construction, but with an admirable durability that did not go unnoticed.

For two centuries after Ibn al-Shaykh’s visit, the lighthouse of Alexandria was still in use, for its function in the seaport was essential. Boats were controlled and guided from it, and their sailors, frightened after often hazardous journeys, felt relief in their hearts after glimpsing it, as we know well from written testimonies. Ibn Battuta of Ceuta ,who visited Alexandria in 1326, just three years after the earthquake that toppled it, pointed out that “one of its façades was in ruins”, and when he visited the city again in 1349, “it was such a total heap of rubble that it was not possible to get into it anymore, nor even to go up to its door.” It was replaced by a small watchtower (al-nazura), that stood until 1447, when the Mamluk Sultan Qayt Bey built over its ruins a fortress to which he gave his name.

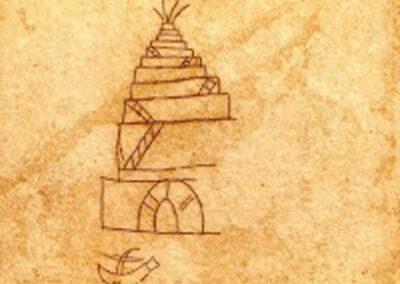

The enduring descripction of such a powerful Lighthouse ̶ said to be the Seventh Wonder of the Ancient World ̶ by Ibn al-Shaykh, has allowed modern architect M. López Otero to reconstruct quite accurately, on paper, its shape and elevations, adding suggestions on other existing interpretations.

The Lighthouse of Cadiz that existed in ancient times was the beacon for Phoenicians, Punics, and Roman sailors who arrived at the westernmost part of the Mediterranean from the east. We know its shape thanks to the depictions that appear in several Arab texts, and also by the wall painting dated two thousand years ago, which was found in the Roman salting factory located in the ancient site of the Teatro Andalucía in Sacramento Street in Cadiz.

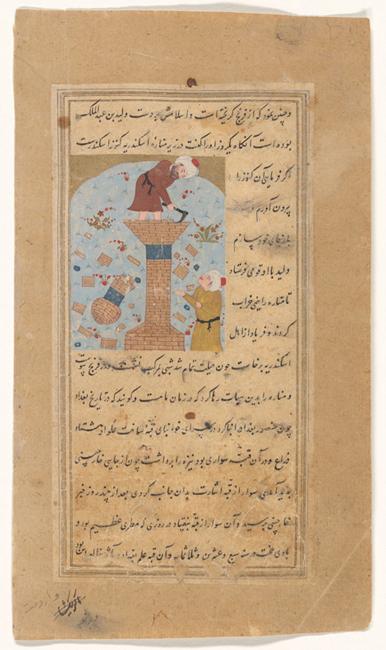

Manuscript dated in the 16th century, with an illustration of the account by al-Qazwini, according to which a foreigner, who claimed to be a convert to Islam at the hands of Walîd ibn ‘Abd al-Malik, climbed on the Lighthouse of Alexandria to pick at the masonry because he believed that the wealth of Alexander was to be found within.

©Spencer Collection. The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/36250750-28ec-0138-8835-491d3639a52f

BIBLIOGRAPHY

|