Ibn Arabi of Murcia: al-Shaykh al-Akbar.

The Greatest Master

By Ana María Carreño Leyva.

El legado andalusí Andalusian Public Foundation

“My heart can take every form:

A meadow for gazelles, A cloister for monks,

For the idols, sacred ground, The Kaaba for the circling pilgrims,

The tables of the Torah, The scrolls of the Quran.

My creed is Love.

Wherever its caravans turn along the way,

Its roads are the path of my faith”.

Ibn Arabi

Ibn Arabi of Murcia was the forerunner of what seven centuries later would be the philosophy of ecumenism. His doctrine, in force along the centuries, preached that the religion of love shall make of the human being a new man, tolerant and universal. Hence, “the universal man involves in himself every reality of existence”.

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn al-Arabi was born in 1165 (560 Hijra) in Murcia, within a noble family of this city, the Banu Tayy, originally from Yemen. His father was in the service of the ruler of Murcia, Ibn Mardanish, known in Christian chronicles as King Wolf. In those times, the Almoravids had imposed their power over the Almohads, and despite the resistance offered in Murcia, a delegation departed to Seville to ally with the Almohad sultan Abu-Yaqub Yusuf al-Mansur, under whose rule was built the Giralda, the aljama mosque of the city. It is said that Ibn Arabi’s father, a military man, took part in this commission, joining the government of the Sevillian sultan, and subsequently moving with his family to what was the capital of al-Andalus.

Ibn Arabi spent the first stage of his life in Seville, where his inclination toward spiritual life was invigorated by the numerous encounters with men and women who would determine his path towards mysticism. He got to know the saints Fatima of Cordoba and Yasamin of Marchena (Seville) who had a significant influence in his life, particularly Fatima of Cordoba, an elderly woman who enthralled the maestro by her physical beauty (he described her as if she was a teenage girl) as well as her luminous inner world. Over several years she became his spiritual guide. Ibn Arabi was by that time about twenty years old, and he was already in possession of a profound perception of spirituality and an important depth of intellectual insight. Those were the times when he undertook a wide range of journeys throughout Andalusia, travelling relentlessly to numerous cities searching to encounter all those pious people of whose existence he knew.

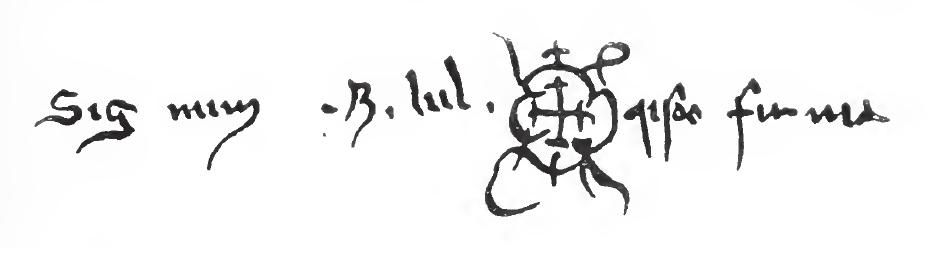

The Sufis, with whom Ibn Arabi spent time during his pilgrimage around the Andalusian geography, prior to his journey to the East, are simple people, not illustrious philosophers or scholars. In fact, they were just merchants, farmers… men and woman whose spiritual profile stood out for humility and generosity. The devotion he felt for these people was such that he featured some essays about them, from which only two have been preserved: Ruh al-quds (The Holy Spirit in the Counselling of the Soul) and Durrat al-fajira (The precious pearl). Imbued by this sense of modesty and simplicity, our faqir (God’s poor servant), did not sign his works in the beginning, and as they were circulating anonymously at his early phase of his literary career, and this has meant that the study of his work has been often taken a great effort.

The Sufis, with whom Ibn Arabi spent time during his pilgrimage around the Andalusian geography, prior to his journey to the East, are simple people, not illustrious philosophers or scholars. In fact, they were just merchants, farmers… men and woman whose spiritual profile stood out for humility and generosity. The devotion he felt for these people was such that he featured some essays about them, from which only two have been preserved: Ruh al-quds (The Holy Spirit in the Counselling of the Soul) and Durrat al-fajira (The precious pearl). Imbued by this sense of modesty and simplicity, our faqir (God’s poor servant), did not sign his works in the beginning, and as they were circulating anonymously at his early phase of his literary career, and this has meant that the study of his work has been often taken a great effort.

It was expected for him to follow his father’s steps and join a military career. Some sources reveal that he even enlisted in the army and that he resigned in 1184, after an awakening mystical vision which was to mark his life: in it, he finds himself in a wide esplanade surrounded by all the prophets who have assisted humankind from the dawn of history, and he initiates a dialogue with Moses, Jesus and Muhammad.

This outcome would be portrayed in his works Ruh al-quds and Fusus al-hikam, (The Bezels of Wisdom) a work of great dogmatic impact that he wrote at the end of his life.

According to certain sources, his father brought this event to the attention of Ibn Rushd, who asked to meet with him. This resulted in an extraordinary crossroads, that of the two people from al-Andalus who were to become the major figures of universal thought: on the one side, the one who would be the most influential Muslim philosopher in the Latin West, Ibn Rushd, and on the other, a gnostic, Ibn Arabi, who was to become the highest representative of Sufism.

Three were the meetings that took place between them. First took place in 1185 and entailed an event in itself. It resulted in an unusual dialogue, almost devoid of words as if thoughts could transmit language directly. From this transcendental dialogue in the young philosopher’s life, which dealt with the resurrection of the body, arose what was to be the corpus of his capital work: Futuhat al-makkiyya (The Meccan Illuminations).

Bearing in mind that Ibn Rushd was a faithful interpreter of Aristotle, it underscored in an exemplary way the relation existing between the rational thinking in Islam and that of the heirs and depositories of Greek philosophy and the Muslim mystics’ doctrines, based on the spiritual experience exposed by Sufism.

An indefatigable traveller

In 1193 he left Andalusian soil for the first time to reach the Maghreb to study the great teachers of Sufism. He first visited Tunisia, where he remained one year with Abd al-Aziz Mahdawi, with whom he wrote several works, among them the aforementioned Ruh al-quds and las iluminaciones de la Meca Futuhat al-makkiyya).

The mystical visions that took place in the North of Africa made up basically the orientation of his doctrine, governed at the command of God to teach men, thanks to the knowledge he had been given, for Ibn Arabi considered himself a “Theo-didact”, instructed directly by God.

After his father’s death, and after spending around a year in Fez, he returned to Seville where Almohad Sultan Yaqub al-Mansur offered him to work at his service, but he was to decline in order to go back to Fez. In the imperial Moroccan city, he lived two more years, and he established valuable fruitful relations with great Sufism authorities, which resulted in what is considered one of his most beautiful works: Kitab al-isra (Book of the Nocturnal Journey).

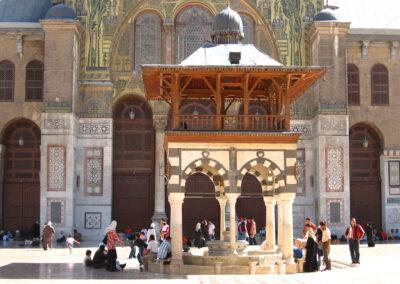

In the year 1198 (595 H.) he travelled around greater part of the Andalusian geography, visiting everyone he had met all along in his spiritual search, and having above all the great honour to attend Ibn Rushd’s funeral. He bid farewell to al-Andalus in Murcia, from where he set off to continue his task eastward −after having another vision in which he was ordered to leave his country− where he was to spend the rest of his life. It was during this tour that a profound change opened in his life. In 1201 (598 H.) he visits Mecca where he had a revelation receiving instructions to write what was to be his capital work: al-Futuhat al-Makkiya (The Meccan Illuminations), whose genesis was set out during his dissertation with Ibn Rushd.

From Mecca, Ibn Arabi continues his travels through different cities, suffering periods in which he was shadowed by problems with jurists that, despite they occurred only occasionally, came to him with certain seriousness, as when he was threatened with death in 1207 (604 H) in Cairo, and he had to return to Mecca to seek refuge. Sometime later, he headed to Turkey, to Anatolia, meeting in the city of Konya with one who was to become one of his most important disciples, the one who was to disseminate his work throughout the western Muslim world, Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi. From Konya he went to Armenia, travelling through the valley of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, and later to Baghdad, where he acquainted himself Sihab al-Din Umar al-Suhrawardi, another grand master, author of one of the leading works of Sufism, the Awarif-ul-Maarif. Aleppo was his next destination before reaching Damascus. He remained there until his death, after having earned a great reputation, achieving acclaims and invitations to the most prestigious courts in different latitudes.

The ensemble of Mevlana in Konya (Turkey) hosts the sanctuary of Jalal al-Dim Muhammad Rumi, the celebrated Persian poet, mystic and Muslim scholar. Upon his death, his followers founded the Mevleví Sufi Order, the order of the known Whirling Dervishes.

©Pixabay

View of the monastery of Khorp Virap and the massive Ararat Mountain in the background (Armenia)

©Destino Armenia

Muslim sacred mountain Jabbal al-Nour nearby Mecca. There is located the cave named Hira, where prophet Muhammad received his first revelation from archangel Gabriel.

King Eliot ©CC BY-SA 4.0.

The contribution of Shaykh al-Akbar −he Greatest of Masters, as he was to be known− to the history of thought is underpinned by his exceptional work, comprising almost 400 titles, as well as in his very life −as it is the case of most of other great wise men−, essentially based on prayer, contemplation and the contact with other mystics and Sufi saints. Being all aligned around his theophanic vision of the spiritual world, we find ourselves facing a great number of metaphysical works that reveal the spiritual and intellectual scope of this Andalusi sage. His doctrine attained the highest levels, regarding both the Islamic and universal thought.

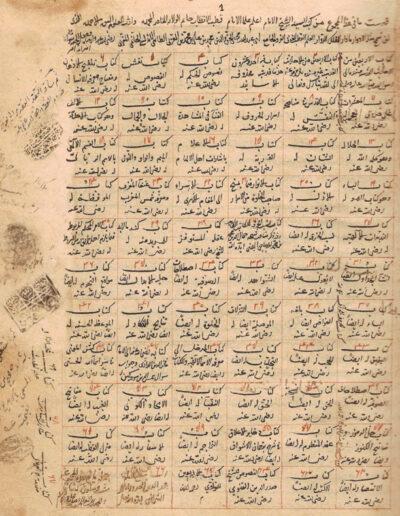

Among the huge number of works by the philosopher from Murcia, the most read, and considered his spiritual testament, is Fusus al-Hikam (The Bezels of Wisdom), which consists of twenty-seven chapters dealing with the esoteric fundamentals of Islam. But his paramount work, given its encyclopaedic nature, is the Futuhat. It comprises 560 chapters that deal with the metaphysical principles contained in diverse sacred sciences, including also his own spiritual experiences. Owing to its depth and authenticity, the dimension reached by this compendium of esoteric sciences that exist within Islam, it became the greatest work of its kind ever written. Among his writings, together with the many treatises and fundamental works, we find also pleasant poetic works −he is also considered as one of the best Sufi poets− with masterpieces as Tarjuman al-Ashwaq (Interpreter of Desires) and his Diwan.

Symbolism and language

The language in which the Akbari work and doctrine crystallize mainly rests on a symbolism that covers all its forms, from the poetic or mathematical to the geometrical. Within the context of Sufism, symbolism holds a paramount value, for it entails the language of the Universe. Every external value has also its symbolic value, as it also happens in the principles of religion and the events that take place in the soul of the human being. Ibn Arabi exposes the reality he expresses in his work by means of this symbolic language −which he also calls “the expression of the ineffable”– that must be unravelled in depth to be revealed.

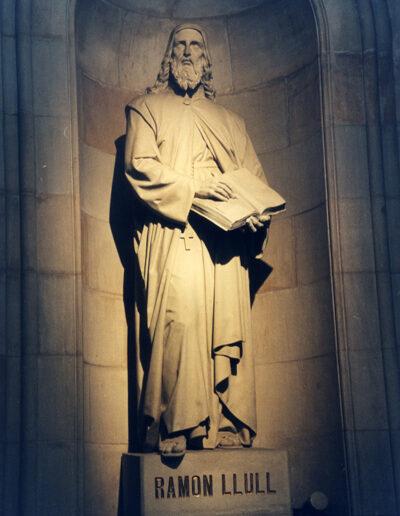

The study of the Islamic thinkers that offered such valuable contributions to literature, philosophy and to the spiritual scope in the West shows how much Latin Scholasticism in the Christian Middle Ages owes to numerous Islamic thinkers. Once Latinized as Alkindi (al-Kindi, 801-860), Alfarabi (al-Farabi, 870?-950), Avicena (Ibn Sina, 980-1037), Avempace (Ibn Bayya, in Latin, around the late 11th c-1139) or Averroes (Ibn Rushd, 1126-1198), they were envisioned, alongside Aristotle, Plato and other Christian thinkers who followed Scholasticism such as Raymund Llull (1232-1316), Duns Scoto (1266-1308) and Roger Bacon (1214-1294), all of them imbued with Sufi thought.

As Arabist Julian Ribera states, Llull himself admitted having used this system; this was the reason why he was considered a “Christian Sufi”, and he used diverse allegories from the teacher of Murcia.

Despite the gap of three hundred years, Ibn Arabi (1165-1241) and Saint John of the Cross (1549-1591) represent in their respective times the height of Spanish culture and thought. Parallelisms or analogies between the dialectic and ideology of both Christian and Muslim mystics is undeniable, giving rise to a range of studies and debates. Let us recall the controversy surrounding Asín Palacios’ thesis arguing that Ibn Arabi inspired Dante when he wrote The Divine Comedy, before the 13th century translations made at Alphonso X the Wise’s request were discovered, being first translated into Spanish and later into Latin and French.

We have made here but a slight approach to the colossal figure of the Greatest of Teachers, and we have had to leave out and summarize many aspects of his life and work given the huge scope of this persona.

CODA

Also known as Muhyi-l-Din (Reviver of Religion), upon his death he was granted the honorary title al-Shaykh al-Akbar (Doctor Maximus, or Greatest Teacher). He was also given the nickname Ibn Aflatum (Plato’s son) when, once Ibn Rushd died in 1198, the exemplary track of rationalist thought was apparently vanishing, while new paths leading to the philosophies of Plato and Ibn Sina (known in the Latin world as Avicenna) appeared in the East.

Ana María Carreño Leyva. Foundation El legado andalusí.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Los dos Horizontes. VV.AA. Edit. Consejería de Cultura, Educación y Turismo. Colección Ibn Arabí. Murcia, 1992.

Las iluminaciones de La Meca. Ibn Arabí. Edic. Siruela. Madrid, 1996.

Revista “Post Data”. Nº 15 Edit. Asociación de la Prensa Murciana.

[1] (l) Al-Jili, Abd al-Karim “De I’homme universel”. Trad. Titus Buckhardt, París, Dervy Livres, 1975, p. 28.