Ibn Battuta, the traveler of Islam

Our traveller journeyed along North Africa, the Middle East and East and Central Africa. After this first set of journeys, he returned to the holy city of Islam, where he lived for three years, to later depart to the south of the Arabian Peninsula, the south and southeast of Asia, continuing to Egypt, Syria, the Turkish region of Anatolia, south Russia and finally Constantinople and the lands of the Golden Horde.

He also lived for ten years in India and the Maldives to undertake his journey farther east: Ceylon, Bengal, China… Around 1347 he was on his way back to Fez where he arrived in November 1349. His journeys to al-Andalus and Niger culminate his extraordinary peregrinations, and he became known as “the traveller of Islam.”

The image depicts al-Hariri helping Abu Zayid to recover his stolen camel. IIlustration of al-Hariri’s Maqamat, as it appears in a manuscript dated 1335 preserved at the Bodleiana Lybrary, Oxford.

For the Islamic world Ibn Bautta represents what in the West embodies Marco Polo (with whom Ibn Battuta concurs in many of his descriptions) or our Ruy González de Clavijo and his embassy at Timur’s court.

They were all intrepid travellers who ventured into that unknown Orient, more affordable for some than to others, since Ibn Battuta took advantage of his Muslim condition and his knowledge of the Arabic language to reach the edges of the Far East, without ceasing to cross Islamic lands,and hence subjected to the use of the Arabic language as “lingua franca”.

His work is complied in the Rihla (journey account), a term that was born in the 12th century to define everything a genre of travels descriptions by the travellers from al-Andalus and Morocco, with clear backgrounds as al-Idrisi native to Ceuta. Even though at some point has been doubt about the veracity of the totality of his account −for his travels started to be written virtually thirty years after having been iniciated− the comparison of the descriptions by other travellers of his time provided credibility to his work, which truly offers quite an accurate and adjusted vision of the Muslim word in the 14th century. In any case, the account was not drawn in its final version by Ibn Battuta, but by the Granadan Ibn Yuzayy, to whom it was dictated, a meaningful detail that explain the relationships that existed in those time between both shores of the Strait of Gibraltar. Ibn Yuzayy added on his own endless literary flourishes, making a geographic lineal development of the work which was not always respected by the traveller.

His wondering life starts in the year 1325, when he leaves Tangiers in direction to Mecca to undertake his first pilgrimage. He then travelled across northern Africa, passing by Egypt, Palestine and Syria to finally reach his destination. From Mecca, he headed towards his second journey to Irak, the north of current Iran and Kudirstan to return to the departing point. Once there, he departs again to travel along Aden, current Yemen, and the estern African coast. His next itinerary will take him to India going through Anatolia, part of Rusia and Afganistan. In India, which was then under Islam rule, he will remain for a period of ten years. From here he continued travelling to the Far East and China, to finally return to Mecca in 1349. But being not content with this journey, upon returns he visits a decadent al-Andalus and Abu Yusuf’s Granada to end up getting into Black Africa, travelling to the Empire of Mali.

While travelling in Central Asia, which was then dominated by the Mogol Empire, he leaves us vivid description. On his course through a desolated Bukhara, he makes a reflexion on the Tartar invasions with these words: “Nowadays, you cannot find anyone in Bukhara who knows something about science or in interested in knowning about it.” In the same way, he describes Gengis Khan as “ the damned Tankiz the Tartar, of a generous soul, vigorous body and great height”, coinciding in this image with the one offered by Marco Polo. He also describes with distresses the final destiny of Bagdad after the Mogol invasion, and he tells the way they “got into the capital of Islam, seat of the caliphate, by the force of arms, and how they beheaded the caliph.”

In his visit to the Maldive Islands he was surprised before the proximity of them, and he remarks that “as you leave any of them, you can see already the top of palm trees of the next one.” Finally, he finds in Damas the example of an Islamic city and uses it as a model of beauty and armony, finding pleasure in using poems as introductions to ooathe other prestigious cities of the time like Aleppo or Baghdad. In China, he is amazed before the size of its cities: from Hang Tcheou-fou- (Zheijang) he writes “It is the larger city that my eyes have ever seen on earth: its length equals three days of travel.”

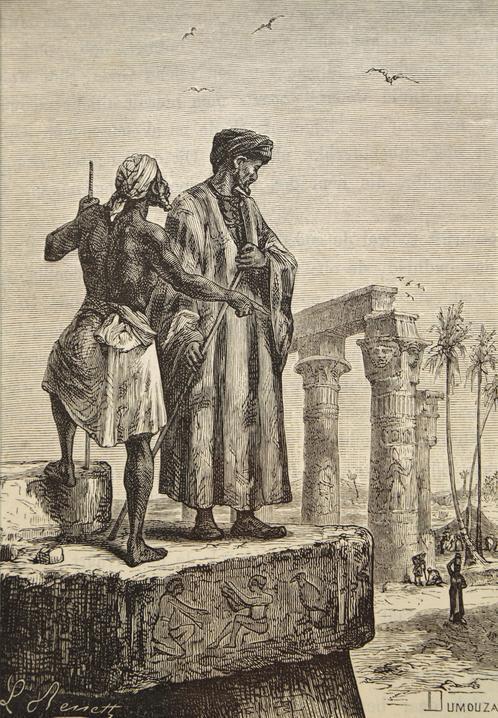

Reproduction by Hippolyte Leon Bennett after an oil painting depicting Ibn Battuta in Egypt.

Equally significant it is also the great amount of remarks that Ibn Battuta makes about the economic and sociologic aspects of the cities he visits. His references to prices is paradigmatic, showing a great interest to get to know the procedure for the development of every kind of commercial practices in far away lands, which is proved in the way he describes the use and coinage of paper money in China, the cashier’s check in Persia, and the Treasure notes in Delhi (india). The descriptions he makes of so varied aspects such as rights on customs, mining, craft industry, the boost of commerce or the movement of ships in the main ports such as Alexandria, Tirp, Calicut (India) or Zaytun (Tshiuan Tche-fou) in China, are lenghty.

He pays special attention to agriculture, as he is amazed before the living green of the orchards in Basora (Irak), from which he says: “there is no place on earth with more palm trees” or the quality of the melons from Kwarizm (Iran), an statement in which Ruy González de Claviojo agrees too.

He also includes in his analysis opinions on diverse minority groups. In this way, being an urbanite as he is, he calls the Bedouines robbers and destructive, but he admires and expresses a deep liking for the fakirs and dervishes Sufi motivated. His attitude is generally tolerant, excepting towards Jews an Christians, with the exception of the triumphant Christians from al-Andalus, to whom he exhibits an agressive behaviour. The situation of women also occupies a place in his descriptions. He includes aspects such as the legal procedures for feminine protection, and the high social regard that Mongolian and Berber women enjoy, as well as the decisión making-power of the women from Maldives when marrying.

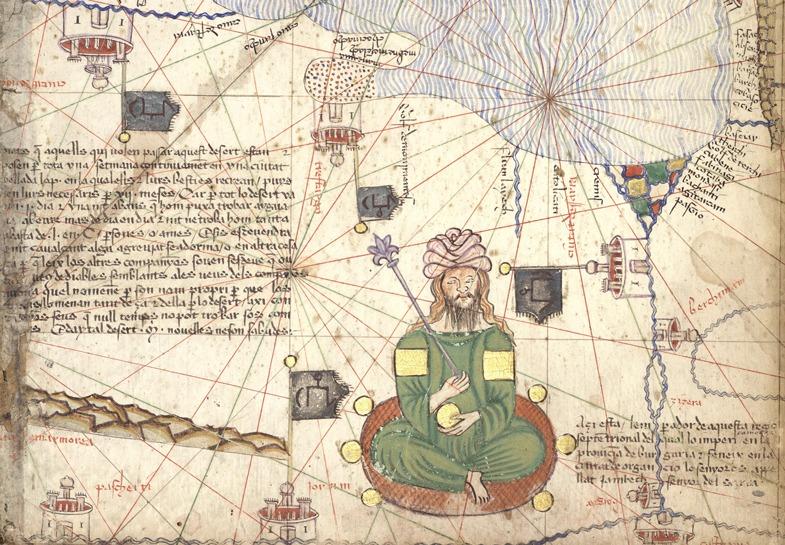

Detail of the Catalan Atlas by Abraham Cresques ca. (1375) depicting the Mongol state of the Golden Horde, which included territories of today’s Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

We know the most human side of Ibn Battuta through many anecdotes. We must take into account that for a man of his times, reality was often warped by legend and the obscurantism that accompanied the description of the unknown. In the frequent fictional episodes he quoted, he denounced aspects like tricks and witchcraft practiced by women. When it comes to judging people, he could not escape his own human passions, distorting their descriptions depending on the way he was treated by them.

As in every journey at the time, the part related to research and espionage was nothing despicable. Ibn Battuta travels were aimed at gathering information for the Marinid Sultan Abu al-Hassan, and the model of Marinid political organization happened to be continously loaded. In this way Morocco came in first place in his ranking of the seven most powerful kings in the world. His travels to al-Andalus and Mali can be understood within the political framework of the unification of the Maghreb that sultan Abu Inan, Abu al-Hassan’s successor, was seeking. In al-Andalus the journey was aimed at ensuring the maritime border of the Strait of Gibraltar, also referring the pressure exerted by the corsairs, which were supported by the Marinid sultans. The task of informing and spying for the sultan is developed greatly detailed regarding how power is organized in the places he visits (like the organization of the Mongol army, or how power is distributed in China).

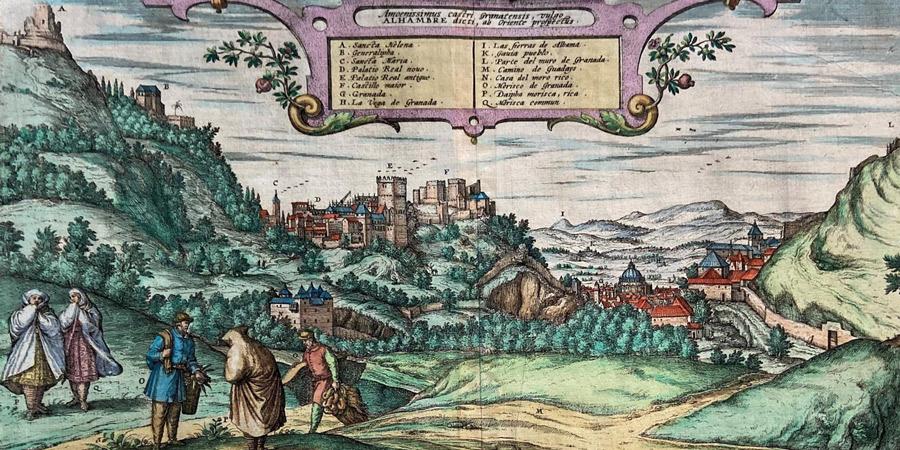

View of Granada in 1572. Civitatis Orbis Terrarum. J. Hoefnagel. ©Wiki Commons

Ibn Battuta’s figure has a significant presence in the imaginary of people, particualrly in the Maghreb. When somebody comments along those lands about the fondress of travelling, the feedback, accompanied by a kind smile, use to be: “Oh like Ibn Battuta!”, so as to underline that his figure represents that of the traveller by excellence in that part of the world.

As a conclusion, it is enough to mention how his chronicler Ibn Yuzay ends up prasing Ibn Battuta, whom he qualifies as the “traveller of the Muslim community”.

Sergio Cebrián Sanz.

Writer

BibliographyIbn Battuta. A través del islam. Traducción de Serafín Fanjul y Federico Arbós. Editora Nacional, Madrid, 1981. |