Ignacio de las Casas, a morisco wise Jesuit a peacemaker between two worlds

PART II

By César de Requesens Moll.

The upheavals that Granadan society experienced in the 16th century, after the uncanny finding of the so-called Sacromonte Leaden Books, and the Morisco issue, gave voice to Jesuit Ignacio de las Casas, he himself of Morisco origin, to search for solutions to the problem of his ancestors.

By analysing the documents in depth (which was possible thanks to his knowledge of both Arabic as Muslim religion, wisdoms that the other experts who studied the texts lacked) he demonstrated that they were an eyewash invented by the Moriscos because there were many references to Muslim culture and religion. In his opinion, an appropriate education would be sufficient to avoid the repetition of incidents as such; in fact, he did not trust the interpreters because they did not have a solid theological and religious formation and besides, as it happened in the case of Granada, they could be handled. De las Casas accused them of being responsible for the upheaval caused by their misinterpretation of the content of the books.

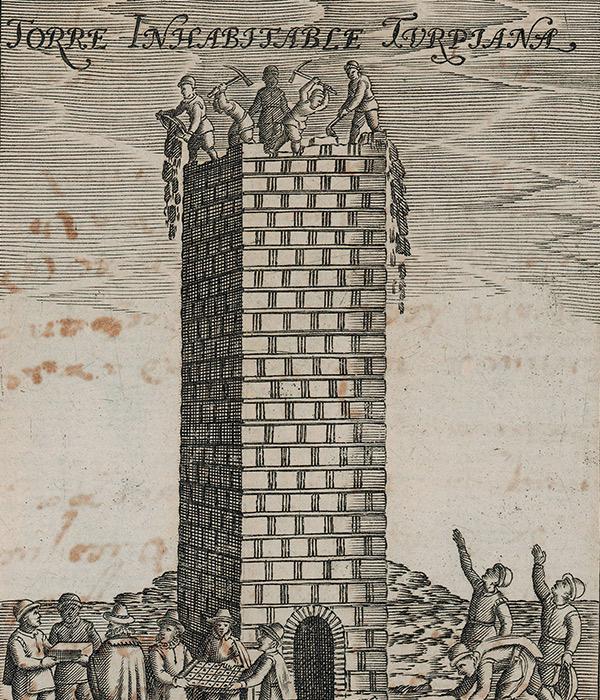

Ilustration depicting the Turpiana Tower, the minaret of the main mosque in Granada, demolished in 1588 to build the cathedral. Scattered amidst the rubble were the relics and parchments that gave rise to the affair of the Leaden Books.

THE LEAD BOOKS. The plot of a novel to save the Moriscos.

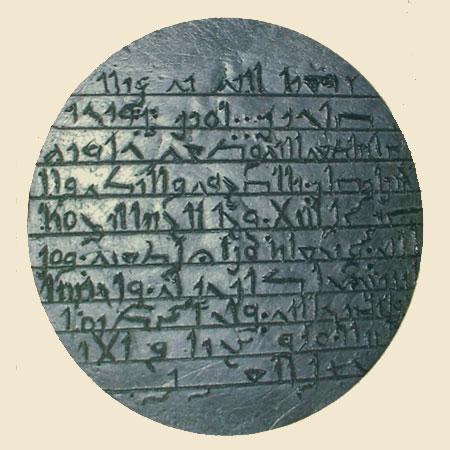

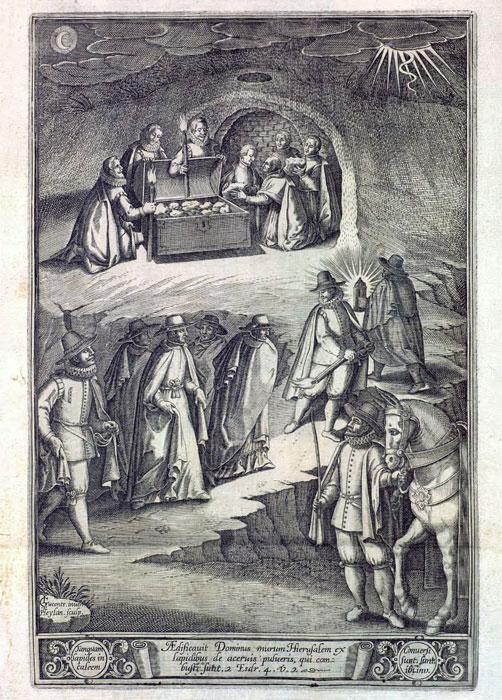

. In the course of the works in the Turpiana Tower of the Main Mosque of Granada (currently the church of El Sagrario, one of the three that compose the ensemble of the cathedral of Granada) to turn it into a church, a chest was found, wherein was found an apparently old parchment that explained that some texts of very old origin would be soon found, containing a revelation to Christianity. The parchment appeared in March 1588, the day of Saint Gabriel, together with a bone and another textile relic, with texts in Arabic, Latin and Spanish. The bishop of Granada was at the time Juan Méndez de Salvatierra. It caused a major stir among the Granadan community, Catholic and Morisco. The definitive expulsion of the Moriscos from Granada was near, and the atmosphere already reflected the tragic decision of expelling the last Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula.

Expulsion would not take place until 1609-1613, at the same time the findings took place, which later was proved to be but an ingenious and complicated plot, half true and half fiction, engineered by an elite of knowledgeable Granadan Moriscos. What these cultured writers did was nothing but to take advantage of the pervasive religious ignorance among the Christian and Muslim population, as they granted written religious dogma equal ranking with mere and vague popular beliefs without further doctrinal foundation.

Through these texts, it was intended to give birth to a Christianized Islam and an Islamized Christianity. With Arabs and their language, Christianity might reach its climax; however, to achieve it, every falsification and misinterpretation in the light of the “true doctrine”, that of the Koran, should be abandoned.

The guiding threat of this fictional plot was the union of the two main religious traditions still present in the Iberian Peninsula. The texts found included, in a free rewriting of biblical events, the immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary, the Paleochristian origin of the Granadan church, as well as accurate biographical data from the first bishop in Granada (Saint Cecilio). In the same way, it had key elements of the Islamic faith. Besides, it claimed the vindication of language and Arab culture, including the one which was God’s favourite by putting it into the very Virgin Mary’s mouth: the praises to this civilization and its culture. Also included were these elements of praise to the city of Granada, placing it like an example to follow both for Christian as for Islamic civilizations and culture.

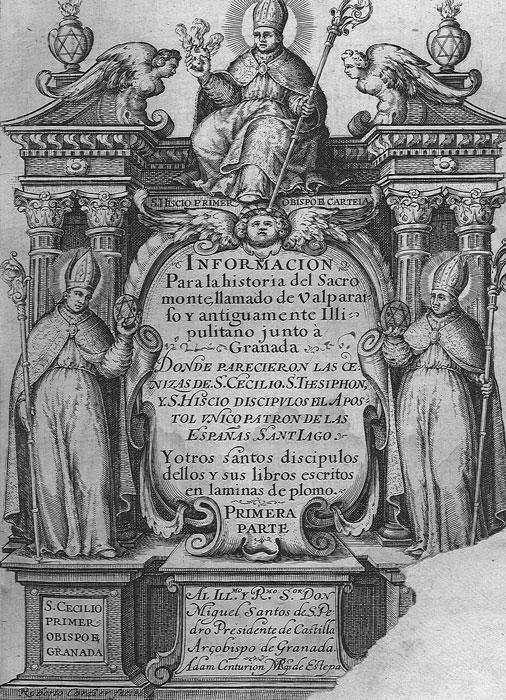

Chalcographic engravemetn by Roberto Cordier representing saints Cecilio and Tesifón before the columns holding the croisiers of bishop and tha leqaden books. Illustration of the frontispiece of Adán Centurión, Marquis of Estepa: Information to tell the story of the Sacro Monte, called Valparaíso and in ancient times Illipulitano next to Granada, Where appeared the ashes of Saint Cecil, Saint Thesiphon and Saint Hiscio, apostles of James, the only patron of all Spains and other disciple saints of them and their books written in lead sheets, Granada, 1632.

In 1590, the new bishop of Granada, Pedro de Castro, showed great enthusiasm on the subject. He firmly believed that the finding of the relics and the strength of its sacred writing was a miracle. The issue then started to get out of control despite the negative report forwarded by the old man Arias Montano, after having analyzed and copied it with the help of his disciple Pedro de Valencia. In his report, he advised that the collection of texts was “old, but not antique”, and neither the letter nor the ink corresponded with the antiquity attributed to them.

Neither the archbishop of Granada, nor that of Seville wanted to hear the voices throughout their mandate that denied the authenticity of the documents. Granada had started to be one more site of pilgrimage in Christianity. Up to one thousand crosses were erected in the road up to the Sacromonte by the faithful devotees, and in 1610, while searching for evidence of the discussed authenticity of the “saint” books, a church was built.

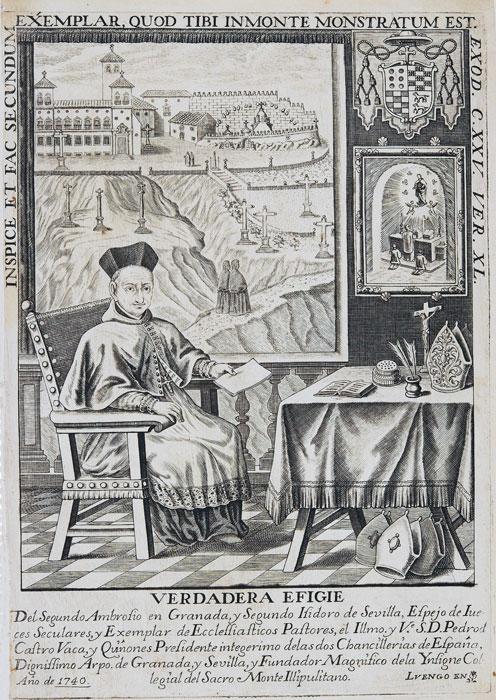

The dream of a union of both beliefs with a common base vanished as if by magic. All that remains of this story is the superb abbey in the Sacromonte, built by archbishop Pedro de Castro, a place where those findings are kept still today. They are preserved as a huge reliquary to house and disseminate for the coming centuries those “revealing” discoveries which, as the Catholic church still maintains, attest to the birth of Christianity in Andalusia and Spain, disputing the post to the Church of Saragossa.

In his requests, it can be observed the sharpness and the ongoing struggle between his Christian beliefs and his origins, as he suffered when he saw his people being despised by old Christians, the Crown and the Church he belonged to.

His enthusiasm for Muslim culture might have aroused suspicion, but Ignacio De las Casas dismissed Islam and the fact of being interested in Muslim culture as he was aimed at the conversion of the Moriscos; indeed, his projects of expanding Christianity demonstrate this.

Notwithstanding his ill health and scruples, he worked in the Morisco apostolate until very old age. He pursued further study of their problematics and methodologies, in search of solutions as well as the knowledge of Islam, the religious and ideological basis of the Morisco opposition to being evangelized. He eventually died in Ávila, in 1608, right after General Aquaviva asked him his expert support in the assemblies in which the serious issue of the “final solution”, the final expulsion of the Moriscos from the territories under Spanish rule, was discussed. But the die was already cast.

By César de Requesens Moll.

Journalist and writer.

Bibliography

| F. B. Medina. Diccionario enciclopédico de la Compañía de Jesús.

Youssef El Alaoui, Universidad de Rouen, ERAC-CRIAR (Francia). Historia de Al Andalus. ‘Ignacio de las Casas, jesuita y morisco’. Boletín n° 52 -07/2006. Benítez Sánchez-Blanco R. De Pablo a Saulo: traducción, crítica y denuncia de los libros plúmbeos por el P. Ignacio de las Casas, S.J. CSIC. Al-qantara: Revista de estudios árabes, vol. 23, Fasc. 2, 2002 , pags. 403-436. Barrios M. “El castigo de la disidencia en las invenciones plúmbeas de Granada”. CSIC. Al-qantara: Revista de estudios árabes, vol. 24. Fasc. 2, 2002, pags. 477-531. VV.AA (Coord. Manuel Barrios). ¿La historia inventada? Los libros plúmbeos y el legado sacromontano. Coedición Fundación El Legado Andalusí-Universidad de Granada. |