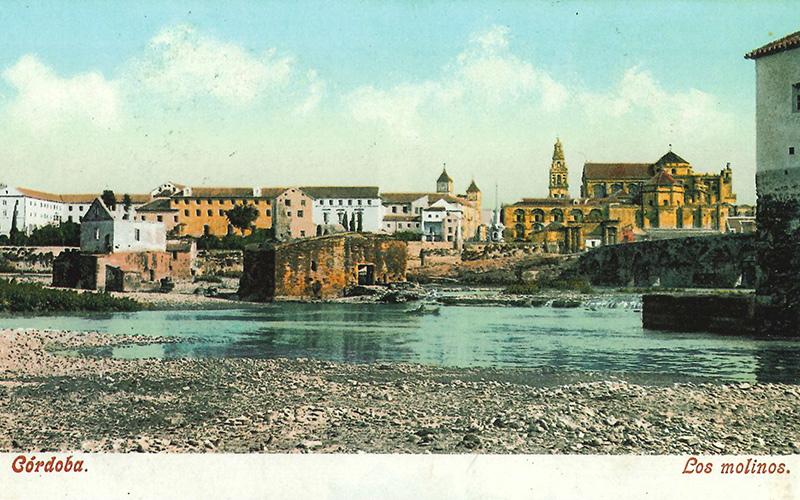

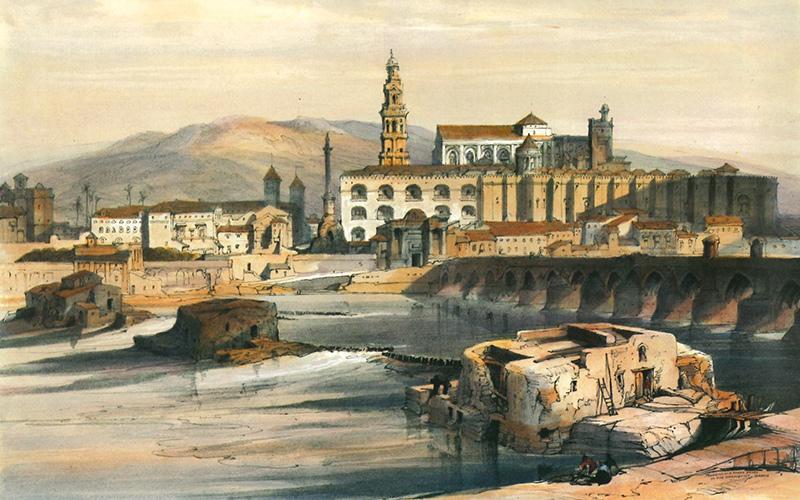

Images of mills and the Albolafia of Córdoba

In the course of the Guadalquivir River along its passage by Córdoba, and next to the Roman Bridge, we find some mills and waterwheels of a very singular character, whose origins give us idea of the raison d’être of the city in connection with the river. Their image has played a key role in the making of the landscape of Córdoba throughout its history, as it appears in the main views of the city that have been drawn since the 16th century until our days, some of which are presented in this article.

According to diverse research on waterwheels, their origins are placed in Eastern Mediterranean towards the 1st and 2nd centuries BC. The first notices about the existence of horizontal waterwheels are to be found in the year 85 BC. Vitruvius described around the year 27 BC the hidromolae (or hydraulic mill), whose basic structure has survived to the present day although such a type would have coexisted with other wheels moved by animals or even by slaves.

Around the 10th century we find the first references to waterwheels used to irrigate the gardens of the residence built by Abd Allah (888-912) in the city of Córdoba.

There is also information from the 10th century about the mills that shared the azuda or the dam with the Albolafia.

The first Christian mention to those Cordoban constructions dates from 1237, when Ferdinand III granted to Don Gonzalo, bishop of Cuenca, Don Tello Alphonso and Don Alphonso Téllez four flour mill wheels, located at the “azuda of Culeb”, as the place could have been named in Muslim times. In 1492, Isabella II ordered the the wood wheel of the Albolafia to be disassembled, because its “rhythmic squeaking” or “repetitive lament” kept her sleepless when she inhabited the Christian castle in the hot month of June. Years later, chronicler Ambrosio de Morales (1513-1591) reveals to us his astonishment by observing “that superb building, now named the Batán (hydraulic machine) of the Albolafia”. Between 1574 and 1588 the nuns of Jesus and Mary owned the wheel of the Albolafia, and they carried out restoration works directed by Juan de Ochoa, the headmaster of the constructions works in the city. According to these documents, it can be underlined that some mills had more than one wheel, sometimes with different tenants, although their ownership was unitary. There are interesting references related to the donation of wheels to the church (with its corresponding part of the channel in the Guadalquivir River) in exchange of a privileged place of burial or masses in memoriam.

Its possible use as factories for paper is an appealing issue but poorly documented, mainly in caliphal times, when a given author identifies the mills of the azuda, under the Roman bridge, as paper mills. It is known that the techniques of papermaking were to arrive soon from the East to al-Andalus, and there is information about the impressive Cordoban libraries, like that of al-Hakam II, which had around four hundred thousand books, or that of Ibn Futais (a whole building with corridors, staircases and shelves filled with books…), which suggests the existence of such industries for the making of paper. Notes about a paper factory also appear around the 18th century, according to which it was in the second azuda under the Roman bridge, next to the current bridge of San Rafael, which disappeared due to the scarce quality of the paper produced, which was not white enough.

LANDSCAPE IMAGES OF CÓRDOBA

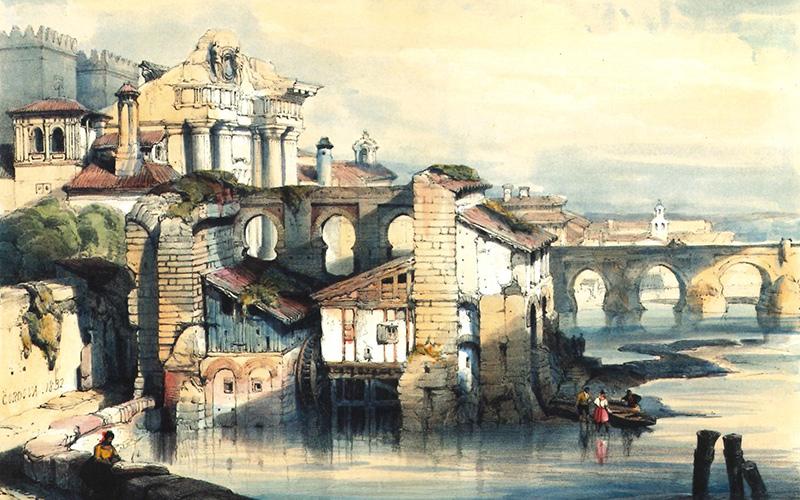

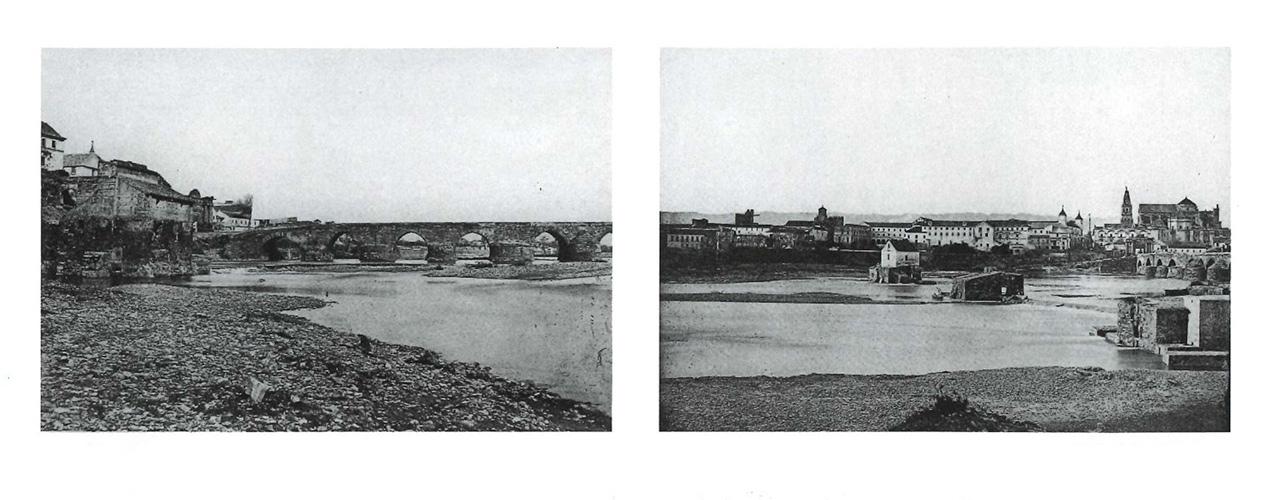

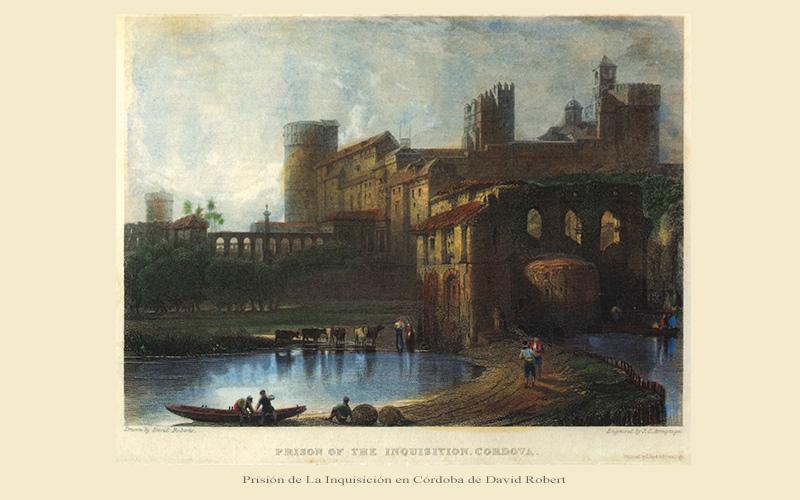

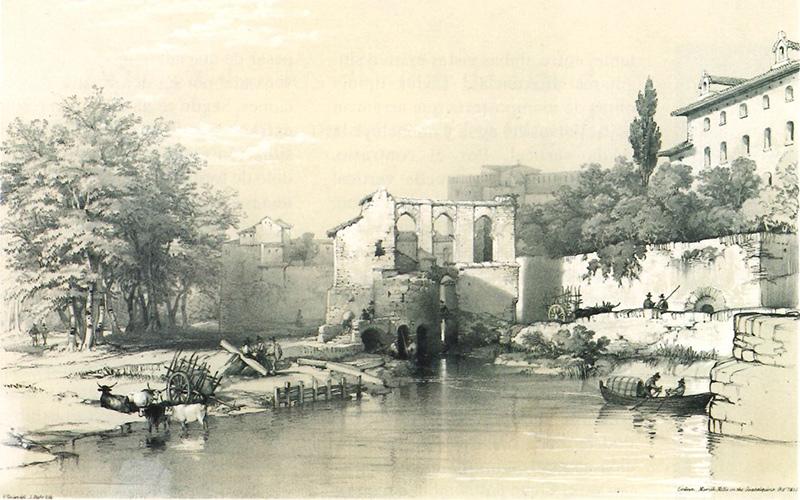

When we reviewed them all, we can observe how Córdoba has been always drawn, photographed, and immortalized mostly from the left riverbank, framing its most photogenic profile: with the Guadalquivir River and the Roman Bridge in the foreground, the mills and the Abolafia alongside, with the mosque and the historic quarter behind, and Sierra Morena in the background. Given the great number of images available, we will only reproduce some of them here, only referring to the closer details and its immediate surroundings, considering that their analysis can lead to a wider and more open research.

One of the first known representations of waterwheels is the one that appears in a stamp of the city from 1357, showing its main features in an idealized form. In the background appear the mosque with its Islamic minaret, its roofs, and the Patio de los Naranjos (Courtyard of Orange Trees). In the foreground and middle ground appear the river and the wheel of the Albolafia, in an exaggerated size in relation to the Roman Bridge, maybe to highlight its historical importance.

One of the most important images of Córdoba along its history is the one drawn in 1567 by the artist Anton of Wyngaerde, painter in the service of King Philip II. It is included in an excellent collection of views of cities practically unknown until they were published in 1986. The drawing includes abundant details of a great credibility, which adds a documental value to it. In the foreground stand the buildings of the left bank, where the Saqunda quarter was, inhabited by merchants and artisans in al-Hakam I’s times. This was to be raided and razed, and later used as a cemetery, until the end of the 15th century, under the name of Campo de la Verdad (Truth Field), where the Arrabal de los Corrales (Quarter of the Farmyards) arose. Small vessels also appear, sailing between the mill of Martos and the Roman Bridge, at the so called Tablazo de las Damas, a place where bathing and boating was common. Downstream from the bridge the Abolafia and the three mills known today as Don Tello’s, (or Pápalo Tierno) Enmedio’s (Of the midst) and San Antonio’s are also drawn. Even then the thick vegetation of its surroundings, today known as Paraje Natural Sotos de la Albolafia (Natural Area Sotos de la Albolafia) was highlighted. The three mills show a single floor and vertical wheels, but the Albolafia appears without its wheel, which was disassembled in 1492 as we have already said. The drawing also details with great precision the architectural elements (stairways, boreholes, even fishing gears), whose information matches drawings that came after them or photographs from the 20th century.

Another engraving depicting Córdoba is included in an important collection containing around 540 views of cities of the world, known as Civitates orbis Terrarum, in its Volume VI, dated 1617. This view had a huge international impact, for there were many of these works in various languages and diverse copies made in the 17th and 18th centuries that are less known (Meisner, 1625; Van der Aa, 1707). Nevertheless, without diminishing the engraving, it is easy to see that the view is less reliable and precise than the drawings of Wyngaerde. In San Antonio’s mill, its vertical wheel has disappeared, its access switched from the right bank. The Albolafia is not drawn, maybe by mistake, and the existence of abundant vegetation is again featured.

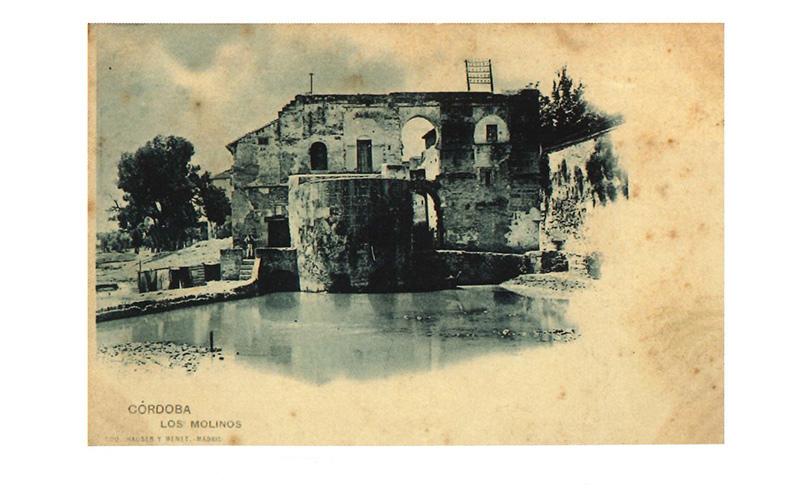

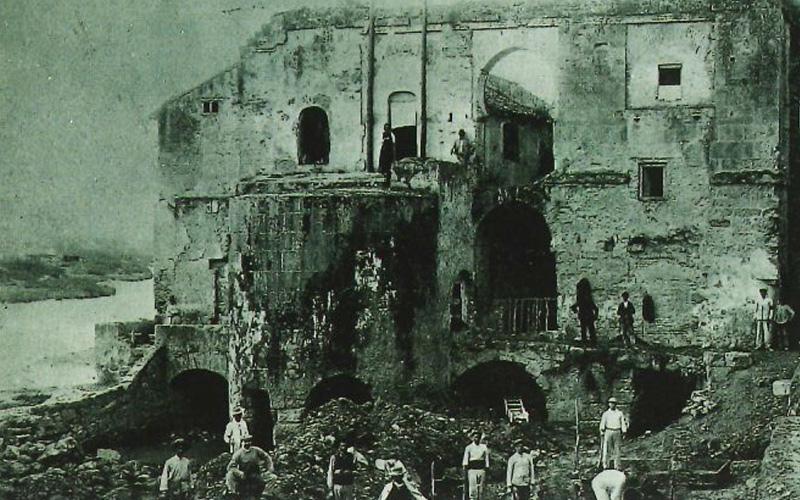

The composition of this façade has been maintained throughout the expansion works of the mill, as shown in postcards from the beginning of the 20th century.

The panoramic view by architect Alfred Guesdon, drawn around 1853-1855, a pioneering representation of the city of Córdoba taken from an aerial point of view, has a great documental precision. It was surely obtained by using early pictures taken from an aerostatic balloon, according to an article published by Gámiz Gordo and García Ortega (2018). Its framing includes views of the river and its mills in the foreground, with the walled city in the background, which verifies the accuracy of its details and is in agreement with those appearing in former images. In this way, in the river’s islets we can see the leafy poplar grove that housed the causeway promenade that surrounded the citadel wall, and the buildings around the Albolafia described in detail.

New graphic testimonials by diverse photographers multiplied in the second half of the 19th century. Among them, the panoramic view by Laurent stands out, which includes the whole bridge and the building of the Albolafia, whose configuration matches with the aforementioned engraving by Taylor. In the other end of the panorama, Don Tello’s mill appears, amplified with one more floor that rises over its original structure.

By:

Antonio Gámiz Gordo, Ph. D. Architect, University of Seville

Diego Anguís Climent, Ph. D. Architect, University of Seville