Leo Africanus,

caravan was his homeland and his life the most unexpected crossing.

By Ana M. Carreño Leyva.

“Leo Africanus may have been for al-Andalus a kind of a posthumous son.

Born at the moment his mother civilization was fading, he learned from exile not only its suffering but also its amazing changes.

At times ambassador, at times slave, adventurer and bureaucrat, he was linked to Islam although he was a well-accepted convert to Christianity through the mediation of a pope from the Medici family.

Leo knew how to keep aside from the hardship of destiny with a calm that was halfway between resignation and manly pride.

For all of us who have remained like him, split between neighbouring civilizations that ignore or repudiate each other, for us who live as he did in times of great ruptures, Leo Africanus bears a symbolic value that transcends his persona, his work and his time.”

Amin Maalouf. Leo Africanus

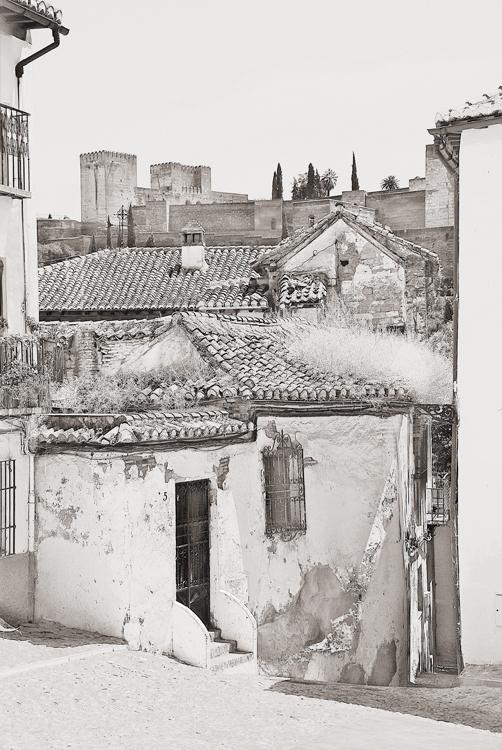

The quietness of those summer days of previous years in the Granadan neighbourhood of the Albayzin had ostensibly little to do with the ones of the later decade of 1400. Most of the orchards that offered their scent to the narrow cobblestone streets already looked either withered or totally dry, now bereft of the care they were accustomed to receive. Abandonment was equally attested to by the loss of whiteness in the facades of the houses, and the small shops, bakeries and the artisans workshops, being closed tight, did not promise a reopening whatsoever. In the streets reigned sort of hidden fear; an odd changeover of donkeys loaded with belongings and heavy packs broke the silence in the narrow streets, in a procession of men, women, children and old people whose grim faces announced the desperate exodus.

What is happening? From the city arose rumours that climbed up the hillside, and people tried to decipher the evolution of events by watching the moves in the Alhambra, which sent messages of discouragement from the opposite hill: torches remained lit for nights, as a sign of the uncertainty in the Nasrid palaces, which caused great unrest in the population.

Albayzín. Granada.

This was the atmosphere of the years prior to the departure of the kid Hassan al-Wazzan’s family. Some three years after king Boabdil abandoned the city, first travelling to the Alpujarra and later to Fez, the al-Wazzan family was also forced to leave their homeland, sharing destiny with the last king of Granada.

Hassan al-Wazzan as a kid could have never imagined what his life would be, when he discovered at a young age that his life would display before his eyes both uncertain and unexpected horizons, far away from the protection provided by the high peaks of Sierra Nevada that enfold his native Granada. His eagerness to know what lay beyond the mountains started already to take off while he accompanied his family in what was the closest thing to a travel: those short trips to the farms that spread along the lush fertile plain in the outskirts of Granada.

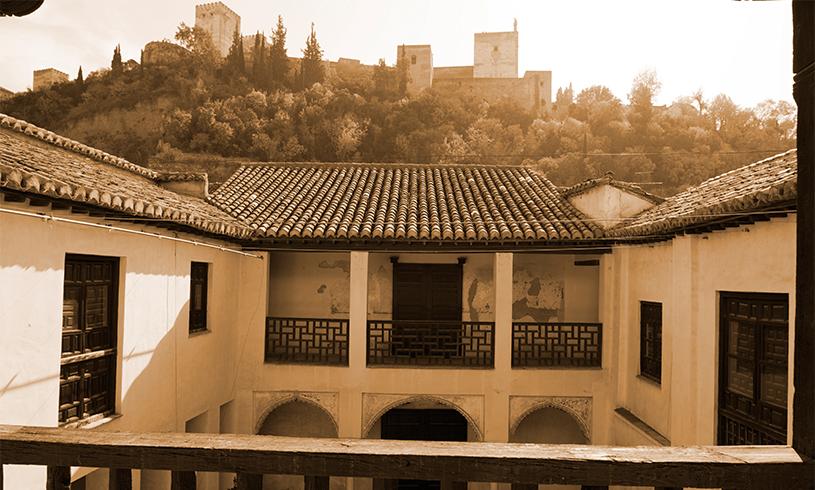

View of the Alhambra from the Casa de Zafra in the Albayzín. Granada.

There is scarce information about his early years; his life was shrouded in mystery, given that his magnum opus entitled Libro della cosmographia et geographia de Affrica, the only source that refers to his biographical data, is crowded with contradictions to the extent of calling its authorship into question.

However incredible as it may seem, the human and intellectual circumstances of this illustrious man from Granada are not widely known, becoming famous only after death. We now know the life of this world-renowned Granadan thanks to the fictionalized story of his life, published in 1985 and masterfully narrated by Lebanese writer based in Paris, Amin Maalouf, due to its publication in several languages.

His childhood and early youth are shrouded in mystery, as we have already mentioned. The many ways by which he was known speak to us of a hectic nature of his long and eventful journey, roaming at times in the haze of history as Hassan al-Wazzam al-Gharnati, al Fesi, Juan León de Medicis, Juan León el Granadino or ultimately Leo Africanus.

His life develops halfway between Renaissance and the fall of al-Andalus, between two continents amid profound historical and political changes.

What is certain is that the al-Wazzan family left the peninsula in direction of the north of Morocco in a moment of great upheaval, in the aftermath of the Reconquest, with the Mediterranean as the stage for the Hispano-Ottoman clash, the Portuguese siege of the Atlantic coast of Morocco and the penetration of the Turks into North Africa. This was the breeding ground in which the adventurous spirit of the young Hassan was forged, despising danger in the interest of a hunger for knowledge of a humanistic character.

Since the origin of his family was Zenata, a tribe that inhabited the steppes of eastern Morocco and western Algeria, from where the Wattasid dynasty, the rulers of Fez at that time, also came, his family was offered an honorific welcome and a promising future, and they should have enjoyed a high social status. In the Rif mountains, al- Hassan al Wazzan’s father was engaged in agricultural exploitation, where he rented land for vineyards and cultivation to local people.

Moroccan desert.

Even before adolescence, Hassan, according to his own, had taken long journey to Babylon, Persia, Armenia, Turkey and Tartary, accompanying his uncle during diplomatic missions for the Sultan of Fez. Due to the experience he gained he started to undertake his own missions for the sultans of Fez and the Sus and, as it is described in his Cosmography, he visited these places either accompanying these personalities, representing them or as a part of the trade caravans, where he underwent all kind of dangers and calamities related to the desert crossing. His stay in Fez is indeed the bulk of data about his biography released in his Cosmography, where he also asserts that he was born in Granada.

The young Hassan had access to privileged education, attending both the prestigious medersa in Fez, the al-Buinaniya, as well as the mosque of al-Qarawiyyin. He studied Theology and Law, obtained the degree of faqih, and he even worked in a maristan (hospital), although he left this occupation when he had to accompany his uncle on a diplomatic mission for the sultan. It was thus that our protagonist began to start to feel the intense excitement of travel, still hardly glimpsing that his life would be but a continual departure.

View of the Granadan neighbourhood of Albayzin.

Panoramic view of the city of Fez, Morocco.

“Thus, wherever the Africans are confronted I will tell that I was born in Granada and not in Africa; and when my homeland is railed, I will argue in my favour that the homeland where I grew up is Africa and not Granada.” (General description of Africa, translation. Fanjul, 137).

He was appointed as the ideal person to accompany the sons of the sheikh of southern Morocco, from whose family would later emerge the Saadi dynasti of the Kingdom of Fez. The group was comprised of three young men aged from ten to twelve years, also Hassan’s school mates, and they undertook the journey to Mecca, probably in 1506. The travel lasted eighteen months. Besides the holy places of Islam, they visited the sites of interest and the most important royal courts from the coast of the Maghreb to Damascus. The knowledge and expertise that Hassan achieved in this journey, led him to being included in the decision of the sultan to join a military campaign to fight the Portuguese invasion of the Atlantic Moroccan coasts. This endeavour had an impact on the young man, whose naturally humanistic character was far from martial activity, understanding that the man’s word was far valuable than weapons. It is in this point when his main skill makes its appearance: diplomacy, a tool that was to become so useful in his future life.

For this restless traveller, the Mediterranean Sea, despite being a place engulfed in danger, was a place he sailed across often, frequently visiting places on his own, without the company of his uncle, ready to undertake by himself diplomatic missions for the sultan of Fez, which took him to Constantinople and Egypt. He took very seriously the task of chronicler, documenting everything and describing in detail and in a methodical way the anthropological aspects, demography, and everything about geography, a key aspect and important support in the art of war. But without doubt it was Nature that would win interest and study over all other disciplines. The scientific effort of our writer helped the development of logistics and administration that had a paramount importance when the expansion of Islam gave rise to a colossal empire.

At his young age he already had a considerable journey upon his shoulders, having visited by then the then most important cities of the time, as for instance the legendary Timbuktu, the quintessential commercial and cultural hub of Africa at the time. This early incursion into Black Africa, to undertake a mission assigned to his uncle by the sultan of Fez, allowed him to know the nomadic world, the fabulous fortresses of the Lords of the Atlas, and the Songhai tribe, in power those days along the banks of the Niger River.

Camels at rest.

This was the initiation trip that introduced him in the vibrant commerce in the Sub-Saharan region, where the exchange of Berber horses for slaves was worth more than the economic transactions with salt, textiles, precious manuscripts and even gold. Here he starts to elaborate detailed descriptions of everything he sees and experiences. His accounts showcase the most relevant questions, interspersed with curious or extraordinary facts. This journey impressed the young Granadan in such a way, that he returned again two years later on a personal mission to explore in depth the South of the Sahara.

Encouraged by the feverish rush of the caravan trade, his intention was to find new markets, as the Kingdom of Fez had lost its ports in the Atlantic while on the other side the Turks menaced the routes coming from Egypt. This was how he starts a sojourn that took him into the shores of the river Nile, and as soon as he set foot in Fez again after having travelled more than one hundred kilometres a day, he faced the desperate situation of the Moroccans, who were suffering the advances of the Christian troops and the revolts of the Atlas tribes. Once again, the sultan of Fez sent Hassan on a diplomatic delegation to the Ottoman sultan Selim I, aimed at obtaining military support, which did not have the results he hoped for. Hassan had then to board a Christian vessel heading towards the Western Mediterranean.

: It is here that the most important part in the life of the Granadan Hassan Al-Wassan al-Gharnati takes place: his boat was seized while sailing near the coast of Tunisia, precisely by a Spanish fellow countryman, corsair, Knight of the Order of a Saint John and captain general of the Pontifical Army, Juan de Boadilla. The high level of knowledge of the captive Hassan did not escape the notice of his captor, who, being astonished before the erudition of the Muslim, offered him to the Pope of the Medicis family Leo X as a gift.

Hassan al-Wassan was captured when his boat was seized close to the coasts of current Tunisia, and he was brought before the pope in the castle of Sant’Angelo, in Rome (in the picture).

Geography in Arab literature

. In the 16th century geographic knowledge was an essential tool owing to Europe’s expansionist fever towards previously unexplored lands. The archetypal models proposed in Antiquity by authors like Pliny, Strabo and Ptolemy present, however, errors in location and also in the chronology of the people who inhabited lands beyond the coasts of the Mediterranean. For instance, the location of Ethiopia (as reported by Rodrigo Santaella in The Book of the famous Marco Polo “you must notice that Ethiopia is the common name given to many provinces inhabited by blacks. Starting at the westernmost part, the first one is Guinea, that is called Cape Verde, and going on toward the sea-coast to the strait of the sea of Suph all those provinces are named Ethiopia…”. The inclusion of Egypt in the African continent, or the course of the Nile River −which Ibn Battuta mistakes for the River Niger− are errors committed also by Leo Africanus as he took for granted the classical authors’ sources: “the part that falls outside the strait of Arabia Felix is not considered a part of Africa despite the many details exposed in long treatises. Latin people call it Ethiopia, from where certain types of monks with branded faces come and are seen everywhere in Europe, especially in Rome. This country is dominated by a chief who is sort of an emperor named by the Italians Prester John.”

In the same way, contemporary Spanish writers also took numerous references from John Leo’s works, like De Mármol Carvajal, who greatly contributed to the knowledge of Africa, sometimes rewriting fragments and passages of the very Description. This work had a difficult acceptance in the European cultural framework, precisely due to the connection of certain information linked to the descriptions offered by the classical authors of old, notwithstanding the fact that it was the reference work to everyone interested in writing about the continent.

Map of the Middle East and Indian Ocean, 1596.

The publishing journey of the Description of Africa, from 1550 to 1995.

If the life of our persona was to crystallize in an historic context of fast-paced changes, the publishing adventure of his Description of Africa was not less so.

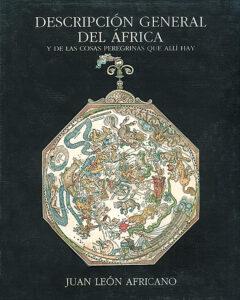

The original manuscript of what is regarded as the first anthropological work (Della descrittione dell’Africa et delle cose notabile che ivi sono) is in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma, compiled in an English bound volume probably dates from the 19th century. Comprised of 470 double-sided pages, its state of conservation is perfect thanks to a painstaking restoration. It presents an impeccable handwriting of high professional level, whose dating leaves no doubt: 16th century. Yet, after many studies, it has been taken into consideration that the original text that Leo Africanus dictated to an scribe varies significantly from the text used by the Venetian geographer and travel writer Giovanni Battista Ramusio in 1550. According to some sources Leo/Hasan wrote the description in Italian and translated it afterwards into ArabicHowever, both the Venetian, as every commentator of the work that followed until early 19th century, assume that the original manuscript was written in Arabic. The work presented by Ramusio was first published as one of those travel collections and geographic texts which had the intention of renewing the existing knowledge of the world, and to act as the witness of the significant changes brought along by the great discoveries. With the publication of the Descrittione, Ramusio offered a valuable contribution to geography, to the development of this science that began to be understood as a modern one. He starts by removing −although progressively− that historical vision inherited from Ptolemy, and replace it with a more precise and scientific conception of the world. The account of the journey of the Granadan’s traveller work is rendered by the different editions that followed that first one of Ramusio . Not without reason Oumelbanine Zhiri entitles Editions, Translations and Treasons? one of the chapters of his work L’Afrique au miroir de l’ Europe: Fortunes de Jean Léon l’Africaine à la Renaissance, (Africa in the mirror of Europe: Fortunes from John Leo Africanus to the Renaissance in which she analysis in great detail the way John Leo’s original text has been treated through its diverse editions. Ramusio himself intervened in the text with three main purposes: −; to make the reading of the text easier, according to the language, and to divide the text into chapters − even shortening or modifying paragraphs he did not consider of interest for the readers;. on the other hand, he completed what he did not consider sufficiently explicit or rigorous as an editor regarding any particular theme and, of course, adding sometimes his own personal assessments when a given passage seemed to be too moderate or too implausible. Ramusio’s compilation is nevertheless considered an opus magnum; it appears in Venice en 1550 under the title Navigationi e Viaggi. In 1556 it is translated into French by Temporal, and it is published in Paris between 1596 and 1598. Florianus translates it into Latin ( J. Leonis Africani. De totius Africae descriptione Antwerp 1556). This version is used in the English translation by J. Pory (History of Africa, London, 1600), the Dutch one by Leers and the German by Lorsbach. The Italian manuscript was discovered in 1931. But it was not published in Spanish until 1995 by the Foundation El legado andalusí, whose translation and additional of notes were in charge of Serafín Fanjul, Ph.D., Arabist and historian at the Autonomous University of Madrid.

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY Descripción General del África y de las cosas peregrinas que allí hay. Juan León el Africano. (Traducción, introducción y notas de S. Fanjul). Edit. Fundación El legado andalusí. Granada, 2004.Descripción General del África y de las cosas peregrinas que allí hay. J.L el Africano. (Traducción, introducción y notas de S. Fanjul y Nadia Consolani). Edit. Sierra Nevada ’95 – El legado andalusí – Lumwerg Editores S.A. 1995. |

Cover of the first translation into Spanish of the work by Leo Africanus, published in 1995 by the Foundation El legado andalusí (image)

Cover of the first translation into Spanish of the work by Leo Africanus, published in 1995 by the Foundation El legado andalusí (image)