Ronda, the city of a hundred views

Let’s take a journey toward Takurunna, the Hispano-Muslim city that wavered between the domination of the Marinids from Morocco and the Nasrids from Granada. Now called Ronda, its charms are inscribed along the Route of the Almoravids and Almohads launched by the Foundation El legado andalusí.

Upon arriving to Ronda, I give full rein to the inevitable urge: to stop on the famous bridge, let the eyes wander over its almost one hundred metres height to confirm that I am in that magical city so praised by travellers. On the west side, the Guadalevín river, flowing through the large hollow that one day was a lake, becomes narrower to be encased in the ravine that spills onto the plateau where the city lies. In the background the serrania (highlands) draw their blue boundary across the horizon. Beyond the bridge, the gorge appears in its full width with its houses close by, and terraced gardens perfectly fitted into the stone. The city seems to be looking closely upon itself. These two looks are but the first ones that this self-entangled city offers, which results in endless discovery for those who stroll along the streets.

The gorge divides the city and also determines the course of its history. There is a Ronda Vieja (Old Ronda) and a Ronda Nueva (New Ronda) on each side of the gorge. The first one lies to the south, which is the most interesting one for me. I have set out myself to discover, or at least to envisage, how the ancient Hispano-Muslim city once named Takurunna would have looked like. In that sense, I have the best help possible, that of archaeologists José Manuel Castaño and Pilar Delgado. Pilar makes me realize that the area where the medina (old Arab city) was is now what is called Barrio de la Ciudad (Town neighbourhood)

Just as we just cross the bridge, we turn right in search of Plaza del Ayuntamiento, where the main mosque was located, on the plot of the current Church of Santa María la Mayor.

Casa del Gigante (House of the Giant)

To get there we go across an area where noble villas stand. Many of them hide behind their Christian façades, dwellings from the times of al-Andalus times. This is the case of the Casa del Gigante (House of the Giant), named so for having a sculpture of a giant from the Iberian Age. It is a typical house with a central patio (courtyard) from which every room departs.

It is worth the effort of imagining what this area was like during the last years of the Caliphate, and in the more than fifty years of the Berber taifa of the Banu Ifran. The mosque’s minaret would have risen above the buildings; a hamman (public bath) might had been nearby so as to serve the worshippers before going to prayer. And a variegated urban layout ̶ which today is an open space, the Park of the Duchess of Parcent ̶ would have hosted the souks with their workshops, the alcaicerías (luxury goods market where jewels and perfumes were sold) as well as the alhondigas that harboured both merchandise and merchants. Beyond the souks, overlooking the medina from both sides of the road to Algeciras, the large alcazaba (citadel) stood where the Salesian College stands today.

There is no doubt that in this point, more than in anywhere else, one misses the ancient fortress that, barely one hundred years ago, was still the perfect crown for this city-wall.

Walls

In any case, we can still discern quite a large part of the walled enclosure at the foot of the ancient citadel. The north-east side was the most vulnerable, as it was a city area that lacked the natural border that the north had in the form of the plateau, being hence unprotected.

We come now to the Gate of Almocabar, located further down, in the exit of the road to Algeciras. Juan Manuel Castaño recalls that its name is a reference explicitly to the cemetery, ormaqabir, lying outside the walls. Christians, as soon as they took the city, built the neighbourhood of San Francisco on top of the Muslim graves. This gate and the walls that surround it are in a remarkably good condition, but they show a strange element. Next to one of its round towers there is an embedded Renaissance door from the times of Charles V.

Gate of Almocábar. The Church of the Espíritu Santo is adjoined to its right side, and on the left the Gate of Charles V.

In the search for the old medina, we cross the Gate of Almocábar in search of the Espiritu Santo neighbourhood. The church of the same name looks rather more like a fortress than a temple, something natural since it was started to be built the same year as the conquest, when war was not yet over.

Once we have reached this point, we take the opportunity to visit the city’s outskirts. We take a nearby road that leads us to the hermitage of Virgen de la Cabeza, which accomodates and old Mozarab church. Before arriving, we pause drawn by a new perspective of the city. We are opposite the hollow that we saw from the bridge before, where the river flows smoothly before passing into the gorge. Here, more than anywhere else, we can appreciate Ronda’s condition of acropolis, as it is set on a plateau, defiant, with its houses standing on the edge of the precipice, as if they were an army prepared for the battle.

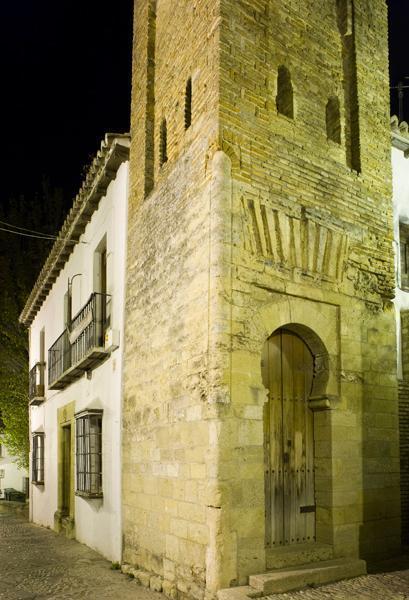

We keep on walking towards the hermitage. There, an old cave church ̶ or a monastery, we should say ̶ carved out of the solid rock, is next to a whitewashed courtyard adorned with borders of flowers. Under the temple there is a domestic area which once accommodated a small community of Mozarab monks. It seems likely that Christian population made up a substantial minority, much more relevant than that of the Jews. In fact, there are other remains of another Mozarab temple: the one named Iglesia de la Oscuridad (Church of Darkness) in the town centre. We will deal with the conquest later on. Now we will focus in what interests us the most: these streets on which the high suburb, one of the outlying districts that, together with the medina, gave shape to the urban layout of Takurunna. The other one, called the lower suburb, has to be searched out at the foot of the medina. We go in that direction, but on the way we stop by the San Sebastian tower, an old minaret reminiscent of the Maghrebian architectonic style. This is not surprising, since at the time it was built, in the 14th century, Takurunna was a tug-of-war between the Nasrid emirs, to whose kingdom the city theoretically belonged, and the Marinids of Morocco, who held Algeciras and Ronda on several occasions as compensation for the aid offered to the kings of the Alhambra against the Christians. This beautiful minaret is therefore the best example to differenciate the history of Muslim Ronda: to have been, over not less than seven decades, an Andalusian-Maghrebian city, as many other North African cities were, and still today are Maghrebian-Andalusian, to a large extent.

Church of San Sebastián, showing the minaret of an old mosque, a clear example of North-African architecture.

In relation to this, Pilar Delgado remarks that the city of Ronda is twinned with the city of Chefchaouen, where the traces of al-Andalus are most noticeable. Descending towards the old suburb we encounter the walls and the Gate of the Cijara, or Higuera (fig tree), a modern reconstruction of the original, executed here, with greater or lesser success, by the architect Rafael Manzano Martos.

The parapet walk that gives shape to the very wall and the barbican, that is, the outer wall that served as a first obstacle for possible invaders, leads near to the Arab Baths. Perfectly preserved, it was not known what they really were until Leopoldo Torres Balbás visited the city to confirm that it was not an ancient synagogue, as it had been said. The vestibule, today free-standing, the three rooms of the baths and the place for the boilers are all preserved. We can also see several pools from a 17th-century tannery. In this area close to the river, despite not having archaelogical evidence that can attest to it, as my hosts clarify to me, we can assert without any fear of being mistaken that there were tanneries, similar to the ones we find today in Fez.

Interior and exterior views of the Arab Baths.

This theory might be reinforced by toponymy: the old Arab bridge, very close to the baths, is also named “of the tanneries”. On top of this construction that probably dates back to Roman times stood the old entrance to the town from the south. Through this humble arch Ronda provides us with its best known symbol: the Tajo (ravine) is shown in all its glory, with its gorge ascending little by little until it meets the impressive arcade of the new bridge, which seems to hold, like a colossus, both walls. This is the opposite scene of the first view I searched for as soon as I arrived in the city. This is the point where we better evoke the takeover of Takurunna in 1485, for it was on this side where the ultimate battle took place. Christian armies devised quite a simple scheme, but that does not make it less intelligent, since they knew that conquering the city was not easy. Once they were facing Ronda, they made a slight hint of abandoning the siege of the city to head to Málaga. People from Ronda then went out in pursuit of them, but they were misled. Christian troops, under the command of the Marquis of Cadiz and Ferdinand the Catholic broke then into the defenceless city and just took it over. In the bottom of the ravine there is still a water well whose control was, logically, of a vital importance. It was enough to take it to force the scarce remaining Muslim troops to capitulate.

As it happened in every city, the conquest meant an urban transformation. Certain areas like the lower suburb were depopulated, others were transformed, like the upper suburb or the medina, and new neighbourhoods were built. José Manuel Castaño remarks that according to the division of lands, Ronda became too small for the Christians. It is no wonder that it had to be so, for the space needs were not the same. In some cases a Christian home was built in the place where six Muslim homes stood before. The construction of new neighbourhoods out of the medina was unavoidable, such as the already mentioned of San Francisco, or the whole area that hangs on the left bank of the Guadalevín river. It was basically on this other side of the ravine that the new Ronda began to take shape. First it was Padre Jesús neighbourhood and then, further up, El Mercadillo neighbourhood. The city grew little by little. Proof of this is that the construction of the Christian bridge, aimed to connect the area of expansion to the medina, was not completed until 1616. The medina kept on being the backbone of the city’s life.

The Church of Santa María la Mayor is set on the ancient plot of the aljama, the main mosque. The mihraband the entrance gate, is all that has been preserved from Muslim times.

We have already talked about the metamorphosis that the heart of the Arab quarter had undergone. Its lower part, by the river, was also transformed. For instance, the beautiful palace of the marquis of Salvatierra was built. Its façade is curious, with naked burlesque figures, which denotes the influence of the indigenous art of America. This is a remarkable example of palace arquitecture but not the most important one. This honour is earned by the palace of Mondragón, whose eventful life began in Muslim times and ends in the present, converted into the Museum of the Town. This building fullfils the dual role of a museum. On the one hand it hosts several rooms dedicated to the museum’s own space, and on the other, its own architecture that over the centuries integrated Mudejar, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque elements, is in itself a unique exhibition area. In my opinion, the most striking element is the courtyard closest to the ravine, with Muslim past but with an ultimately Mudejar configuration. Its gardens, which still bear the stamp of al-Andalus, are a good place to recall that al-Andalus did not end with the conquest.

After the victory of the cross over the crescent, al-Andalus survived among the Mudejar and, later on, among the moriscos, those who were converted to Christianity by force. José Manuel and Pilar tell me that the moriscos also rose up in arms in Ronda. There is a document which talks about the attendance of a Ronda representative to the meeting held at the Albaicin which ignited the rebellion of 1568. Once the insurgents were defeated, their banishment to the lands of Extremadura and Aragon was the preamble of the greater exile to the North of Africa, and the end, this time definitively, of the Islamic presence in the Iberian Peninsula, in the first years of the 17th century.

On the left, Arab bridge. On the right the Curtidurías (Tanneries) Bridge.

We leave the Mondragón palace and keep on going around the old medina, along the ravine, to find again the new bridge. Now it is time to talk about the undeniable symbol of the city which, nevertheless, is relatively young. It was finished over two centuries ago, after forty years of works. This majestic arcade was carefully built after a first bridge, built in a hurry, collapsed, killing fifty people. The bridge allowed for the definitive expansion of the city in the 18th century where it was most feasible: to the north.

The new urban transformation also brought the famous bullring, the most elegant in Spain, a work by Martín de Aldehuela, the same architect who built the bridge. One of the houses that hangs over the opposite side of the ravine, the Palacio del Moro (the Moor’s Palace) also dates from that time. Despite its name, it is not an Islamic work, but rather the cover of the ancient water well we have already talked about. Its more than two hundred steps carved in the stone dizzily ascends the height of one hundred metres.

The image of Ronda was later taking shape as a Romantic myth, reinforced by celebrities who were captivated by the city, like Hemingway and Orson Welles, who is buried here. They helped to consolidate an idyllic image in the 20th century, which was born as an imagined legend, as Rilke described it, which unavoidably degenerated into a simple cliché, into a landscape invaded by topics.

Jesús Cano. Arabist and writer