Samarkand, in the heart of the Silk Route

By Mohammed el-Razzaz (Camel)

Whoever wants to travel to China will have to cross seven seas, each with its own colour, wind, fishes and breeze, each different from the following one.”

Kitab al-Buldan (Book of the Countries) by the geographer al Ya’qubi (9th c.).

The caravans arriving to China by land following the ghost trail, known as the Silk Road, knew well, however, that the mere fact of visiting Samarkand deserved attention in itself, and warranted the eight thousand kilometres that separate China from Eastern Mediterranean.

From time immemorial, Samarkand has fascinated travellers, pilgrims, and even conquerors.. Alexander the Great did not have to cross al-Ya’qubi’s seas when he conquered it in the 4th century, or that is to say, when he thought he had conquered it. Actually, it was he who was conquered, and he acknowledged this with these words:

“Everything I have heard of Samarkand’s beauty is true, excepting that it is still more beautiful than I could ever had imagined…”

Arabs did not have to cross seven seas either when, in the early 8th century, they marched to the western boundaries of China, attracted by the legendary fame of Samarkand and Bukhara. They just had to cross a vast terrain and a river to reach bilad ma waraa al-nahr’ (the field beyond the river), meaning beyond the river Amu-Darya (to the south of present-day Uzbekistan, formerly known as Transoxiana, which comes from Oxus, the Greek name for the Amu-Darya) to finally conquer Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand.

In 750 the Arabs confronted the Chinese (who had looted Tashkent) in the Battle of Talas and defeated them. The second-best secret kept by China (after sericulture) was revealed to the Arabs by the Chinese captives: papermaking thanks to… trees! The first paper factory in the Islamic World was set up in Samarkand. Next, it would be Baghdad… and the world changed forever.

But prosperity of Samarkand and its splendour faded away when, in the 13th century, the ruling Khwarazmian dynasty murdered the Mongol tax collectors, giving Genghis Khan the perfect casus belli: an entire city was completely razed in 1220. This offense faced harsh punishment, washed with Uzbek blood, the survivors telling in every direction the horrors of the genocide, as if messengers of hell. The assault triggered a domino effect, and streams of refugees fled before the Mongol advance, which expanded like a plague to other points of Central Asia, Persia and the Middle East.

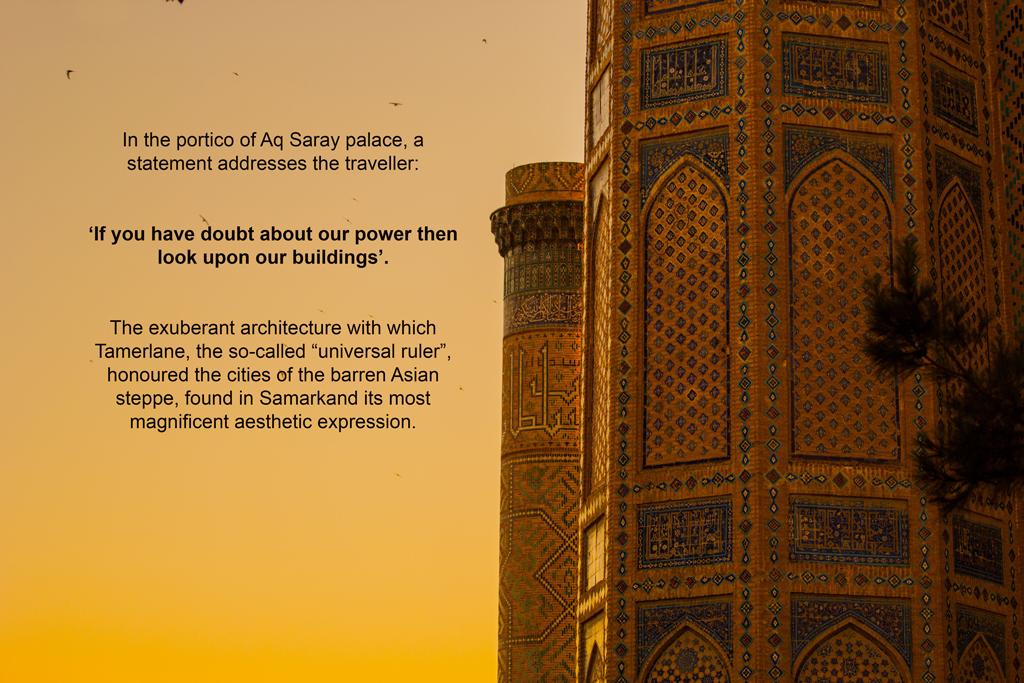

Ghuri-Emir: The other face of Tamerlane

Samarkand rose again like a phoenix from 1370, once it recovered from the trauma and under a new Mongol leadership no less cruel that that of Genghis Khan: the one of the horrific Timur (or Tamerlane, as he was called in the West), who made it his capital. Here I am, under the Ghurí-Emir’s beautiful bluish dome, trembling before the tomb of the very Tamerlane, recalling a story that an old man from Uzbekistan told me some years ago while he was leading me to a typical maison d’hôtes: when Tamerlane’s grave was opened, Russian anthropologists −unknowingly− sparked a curse in their country, and Russia was conquered the next day by Hitler! Was it the Uzbek version of the Curse of Tutankhamun?

Tamerlane oscillated between the brutality of a tireless warrior and the refinement of an extraordinary patron. This mixture of coarseness and refinement shows the paradoxical reality of such a complex world. What is certain is that Samarkand flourished, becoming a hub of institutions aimed at education and pilgrimage, hosting superb palaces, medersas (religious schools) and mosques built by architects and craftsmen brought from all the conquered territories, from China and India, even from Iraq and Syria. Besides poets, scholars and scientists enjoyed his patronage as well as that of his son Shahruj, who extended his attention to musicians, artists and artisans of every kind. The city earned such noble and prestigious titles as “the Rome of the Orient”, “the Eden of Ancient Asia” and “the Pearl of the Islamic World”. This was to change dramatically in the 16th century after the transfer of the capital to Bukhara by decision of a new Asian dynasty.

In the kingdom of the astronomer King

Within this empire there was to emerge in the 16th century a great political figure, a descendant from the Mongol family who, strangely, showed no interest in the “art” of war, a man with a clear vanguardist profile for his time.

Tamerlane’s grandson, Ulugh Beg (1394-1449), governor of Samarkand and other areas of current Uzbekistan, was moreover a patron of poets and scholars as well as masters of the whole region of Central Asia and Persia. He was the great driving force behind the building frenzy, and his reign marked a renaissance whose vestiges can still be seen in the three medersas he built, the most splendid of them shining in Samarkand.

But he was also an astronomer, and more than an astronomer, he was also a mathematician and a poet. His astronomy charts were described as the most complete until the appearance of Tycho Brahe’s in the 16th century. While approaching his observatory (called Gurjani Zij, from the 15th century) in Afrasiab (north of Samarkand, in current Uzbekistan), I have thought how cruel destiny can be: this universal man was murdered by his own son, Abdul-Latif, who in his turn was murdered by his own soldiers.

Ulugh Beg disappeared, but his legacy survived in the kingdom that really matters: the kingdom of heaven. A lunar crater has been named after him, and the astronomer king was to live eternally next to the stars that he never got tired to observing.

Registan: Magic begins

Samarkand is the heart of the Silk Route, and the Registan is the heart of Samarkand. Can anyone imagine how splendid it is? No, nobody can imagine it until having it in front of his eyes, thrilled and wordless before the most fabulous monumental ensemble in Central Asia.

Here, people gaze without batting an eyelid at the three wonders standing on the three sides of Registan Square, three medersas whose façades offer to us a complete overview of Mongol art. Oddly, the name Registan means ‘sand square’, because sand was thrown there to clean the blood of people condemned to death (it was the preferred place for public executions). On the left stands the façade of the Ulugh Beg medersa, built by Kovamidin Shiruzi (1420), adorned with stars that pay homage to Ulugh Beg, who −instead of burning cities as his grandfather Tamerland did− delivered speeches about astronomy in this same medersa.

The day clears gradually, the sun begins to set, and its rays, the ambassadors of the kingdom of light, start their daily game on the floral leaves drawn at ease and in extreme precision on the walls bearing the marks of draughtsmen and painters from times long past. Intertwined leaves and stalks give in the temptation of light, and the words written centuries ago by master calligraphers come alive.

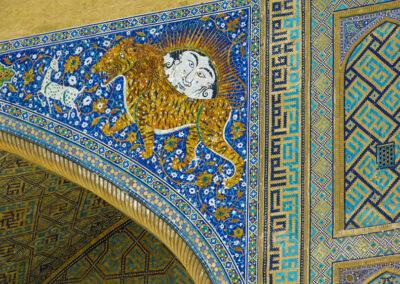

But what a surprise! The sun is facing another sun! And this is because on the opposite side of the square (to the right), stands the famous medersa Sher Dor (‘the Lion medersa’), built in 1636 by order of governor Yalangtush Bahadour. Just a glance suffices to understand that the architect Abduljabbar tried to reproduce the exact copy of the medersa Ulugh Beg. As for its decoration, the theme is distinct: instead of stars we see two lions that look like tigers and a sun rather looking like a Mongol face. The two medersas stand at opposite ends of the square, with another medersa dominating the third side and forming an “U”: we are referring to the medersa of Tilya Kory (the golden medersa), also built by order of Yalangtush in 1660. The façade had to show a different character, and this explains the floral motif which adorns it.

On the outside, the ensemble enjoys a hypnotic beauty and, inside, a perpetual peace and quiet.

One of the most typical elements of the medersas of that epoch is the pishtak (a monumental entrance with a huge arch, flanked by two column-shaped towers), which leads to a vast central yard with trees. Every side contains a centred iwan [1] and rooms arranged in two floors to accommodate students from all over the world, among them such outstanding figures like the Persian poet Omar Khayyam, the genius who wrote the Rubaiyyat. It should not be surprising that Uzbekistan’s cities offered the world thought leaders as iconic as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Biruni, al-Khwarizmi (known as Algorizmi in the West), al-Farghani (Alfraganus), al-Bukhari and others. Cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, Khiva, Tashkent and Fergana became knowledge hubs as important as Fez, Kairouan, Cairo, Damascus or Baghdad. The reason for the cultural blossoming has a long and turbulent story behind, which we better explain after visiting other of the symbols of Samarkand: Shah-i-Zinda.

Shah-i-Zinda: Flight in a dream of blue

We find ourselves facing the Mongol style in its full glory, with its giant space-blue domes, a wealth of bluish majolica, epigraphic friezes whose calligraphy flows like the rivers of Samarkand, floral and geometric motifs interlaced to infinity and a formula that combines solidity and elegance.

Earthquakes have scarred some of the monuments, but Shah-i-Zinda is still standing during the inclement weather. Shah-i-Zinda (‘the living king’) is a huge mausoleum space presided by domes coated with friezes combined with calligraphy and glazed ceramic in blue. The melancholic tone of this cemetery adds stillness and solemnity, at the same time that countless façades, loaded up with some of the most splendid majolica walls in the world, provide the visitor a tour-de-force regarding the talent of potters, ceramicists and painters, bequeathed to us by means of the grandeur of the precious tiles that hold all tones and hues of blue.

In the distance, the calm voice of a man reciting verses from the Koran leads us to the most venerated tomb in the ensemble, Qusam Ibn Abbas −a cousin of Prophet Muhammad who had arrived with the Arab conquerors− who had died in this city. Here, kings do not rest in a conventional sense… here rest the kings who belong to another kingdom, those who live like saints in the hearts of their followers.

Sinbad the Sailor’s Market

“I travelled to Basra accompanied by a group of traders and colleagues… I felt dizzy by the waves… but I soon recovered, and we travelled around the islands buying and selling.” (From the tale “Sinbad the Sailor”, from The One Thousand and One Nights).

Many are the fantastic tales about Sinbad in the Wak-Wak Islands, the Women’s Kingdom, the Valley of Diamonds and the Ali Baba’s Cave, but apart from that, a parallel world not less magical really existed in Samarkand as well as in other places of Central Asia and Persia. It was a world whose characters included ghost caravans, Persian magicians, cursed princesses and enlightened mystics, a world of far-off bazaars, secret ports, scented markets, workshops of blind miniaturists and … wait a minute! Have you said blind drawers of miniatures? Well, yes, they were masters of their craft after decades of experience improving their style.

During Tamerlane’s reign, the ‘arts of the book’ reached its peak of perfection, one never before achieved, thanks to the masters from Baghdad and Tabriz. Miniatures are nowadays one of the most appreciated merchandises from Samarkand; generations of young artisans offer works of quality, although it might be a better option to search for the older ones, whose works show the authenticity and expertise of this tradition. Another ‘compulsory purchase’ is the suzani, typical fabric of the region, traditionally in silk −but no worries, at affordable prices− featuring all the motifs imaginable, but above all colourful floral shapes. Samarkand’s women work wonders with silk, and it may have to do with the geographical situation of the city, located in the very heart of the Silk Route.

It is time to listen to a new-old story… a narrative of passion and treason that is still told in Samarkand’s starry nights.

Bibi-Khanym: The Kiss that rocked an empire

It is said that Tamerlane was madly in love with his young wife Bibi Khanym and decided to build a unique mosque and mausoleum for the wife of the “sultan of the times.” According to the witnesses of the constructions, Tamerlane brought along around ninety elephants from India for lifting the stones. But something remained uncompleted, and no architect was able to finish the construction due to a technical challenge.

Finally, a young architect approached Tamerlane to offer his service and accepting the menace of the sultan. However, despite the young architect’s technical skills, he yielded to the temptation of forbidden romance and, taking advantage of the sultan’s absence, he seduced the beautiful Bibi Khanym: the completion of the building had a price, and it was a kiss of the princess. The story here turns blurred, but what seems to be certain is that the architect kissed the princess, and Tamerlane discovered it upon his return.

How horrible! We better not reveal here what was the architect’s destiny, but the princess’ punishment was far laxer: apparently, she was condemned only to not to be allowed to leave the palace. The sultan who had conquered the whole Orient could not pretend to be tougher with his princess.

The lavish life during the Mongols’ heyday, the magnificence and power they held is in evidence in the two huge domes by the monumental façade. Such power attracted many ambassadors, from among whom two stood out. Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo and Ibn Khaldun have something in common: they both travelled to Samarkand at the beginning of the 15th century to meet with Tamerlane, albeit for very different reasons. The Madrid-born one was the ambassador of King Henry III to Tamerlane because Henry wanted to form an alliance against the Turks, while the great Arab historian just wanted to meet with him. The first one failed in his mission. However, he left us a very important literary legacy, and the account titled Embajada a Tamorlán (Embassy to Tamerlane) shares some similarities with Marco Polo’s stories (Book of the Marvels of the World).

Now, we still have the last excursion away from tourist itineraries normally visited by French and Russians. We thus propose the lesser-known mosques in the city: Hodja Nisabbador, Imam and Aksaskal, which are each an oasis of peace. Samarkand’s Jewish quarter is another hidden treasure. An elder woman watches us, realises we are lost and, not knowing how, she takes us to the synagogue we were looking for, with a proud smile.

The city has mesmerized us, the call of the Registan is irresistible, and shortly afterwards we are again in front of it. The night creeps in, and the illuminated domes od Samarkand shine like celestial orbs, aware of their splendour, which continues to fascinate all the lovers of fine things in this world.

Mohammed EL-RAZZAZ (CAMEL)

Writer and Professor of Meditarranean Culture.

1 An iwan (in Persian: ایوان eyvān, in Arabic: إيوان Iwan, also called iwan, eyvan, in Turkish) is an architectonic space consisting in a rectangular hall or porch under an arch, usually vaulted, walled on three sides, with one end open which forms the characteristic gateway known as pishtak.

Decoration from the portico of medersa Sher Dor (Medersa of the Lion), in Registan Square, built in 1635 by architect Abdul Jabar.

©LoggaWoggler. Pixabay.

Detail of the interior of Ulug Beg’s mosque. It is said that, among his vast knowledge, this king was also a polyglot, for he spoke Arabic, Farsi (Persian), Chaghtai Turkic, Mongolia, and some Chinese.

Uzbekistan©Falco.Pixabay

View of the Sha-i-Zinda monumental ensemble, composed of several mausoleums, among them the tombs of two of Tamerlan’s wives and, according to legend, of a Muhammad cousin. It also has a medersa and a mosque.

Shah-i-Zinda ©Creative Commons CCO.1