Sicily’s Mediterranean Heritage

In the middle of the Mare Nostrum, where the coastal lands of East and West meet, the island of Sicily represents a sort of omphalós of the ancient world, a point of transit and, at the same time, of belonging.

In the middle of the Mare Nostrum, where the coastal lands of East and West meet, the island of Sicily represents a sort of omphalósof the ancient world, a point of transit and, at the same time, of belonging. In modern times, the whole island is overlaid with authenticity, of a veracity only given over to those territories with exceptional particularities.

For this, it is a land prone to clichés: the Mafia, on the one hand, and the frequent eruptions of the volcano Etna, on the other, have pushed this region too often to the world media, to create this cliché, embraced by all, of a land of vendettas, la omertáand the uncontrollable violence of nature unleashing vulcanism and seismic disturbances. Yet, as it usually happens, clichés hide realities of great complexity and richness. And there is no doubt this is the case of Sicily.

The island, although we should say “the islands” ─because apart from the big one, there are others: Aeolian, Aegadian, Ustica, Pantelleria, Pelagie, which comprise the Sicilian region─ represents the quintessential of the Italian Mezzogiorno. This concept, together with that of “the North”, helps to divide the beautiful literary creation that is Italy into two halves, one poor and the other wealthy. The southern half of the Italian peninsula, together with the two big islands, is known by its condition of ancestral land, closed to external influences, as opposed to a north always close to the neighbouring influences of Central Europe.

The obviously insular condition of Sicily explains only in part some of the flukes of its fruitful history.

Opposite to the island of Sardinia, on the far shore of the continent and with the peculiarities of its own situation, Sicily has been always connected, in a way, to the south of Italy, in particular to the Calabrian region, from which it is separated by the 3 kilometers of the Strait of Messina. This explains the historic continuity between southern Italy and the island, although we should not forget the pervasive fact of its being an island that has contributed to developing its own character.

This fact is actually what explains the poverty of a land subjected to some archaic structures that have pressured a great part of its population to emigrate outside the island.

Once the prosperous granary of imperial Rome, Sicily was to become in the Middle Ages and modern times a closed society, a process that was to culminate in the 19th and 20th centuries when extreme poverty, which resulted from the feudal ties that created patronage for the mafia, became something that even incorporation into the Kingdom of Italy (1860) could not redeem. Sicily’s shape resembles an isosceles triangle whose apex faces west. Dominating the island with its 3,345 metres of altitude, the legendary Mount Etna is the place where people of old located the forges of Vulcan and the Cyclops, and it is the tallest and most active volcano in all the continent. Etna’s repeated eruptions ─more than one hundred since the 5th century BC─ have served more than any other fact to build the historic personality of Sicily. In spite of its danger, Sicilians have not been able to subdue a mountain that, despite showing itself indomitable, they have first settled upon its slopes and later turned it into a tourist attraction.

The history of Sicily exudes Mediterranean personality. This land has witnessed the transit and establishment of all the people that have created the concept of Mediterranean culture (Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Arabs, Normans, Germans, French and Spanish) to end up integrated in the Italy of the 19th century to representing now the quintessence of Italian.

The similarities between the souths of the two European countries most genuinely Mediterranean, Italy and Spain, are blatantly obvious. To avoid exaggeration, which is itself a southern cliché, we can affirm that there are no other regions on the shores of this sea with such intense historic journeys, and so many high expressions of culture that remain as witnesses to the diversity of cultural overlaps, like Andalusia and Sicily. Both of them are often regarded as “lands of excess”, where everything surpasses limits without moderation. The Hispanic south and Sicily welcomed the art of the Counter-Reformation, the Baroque, which meant the occupation of streets and public spaces. The cliché of “the extreme” in southern culture certainly responds to the expressions of its inhabitants, with a popular religiosity that moves away from the discreet Christianity of the north. This Catholicism, Baroque and disproportionate, which gets out into the streets during their respective Holy Weeks, shows the ways both regions understand life, so close to each other in some aspects.

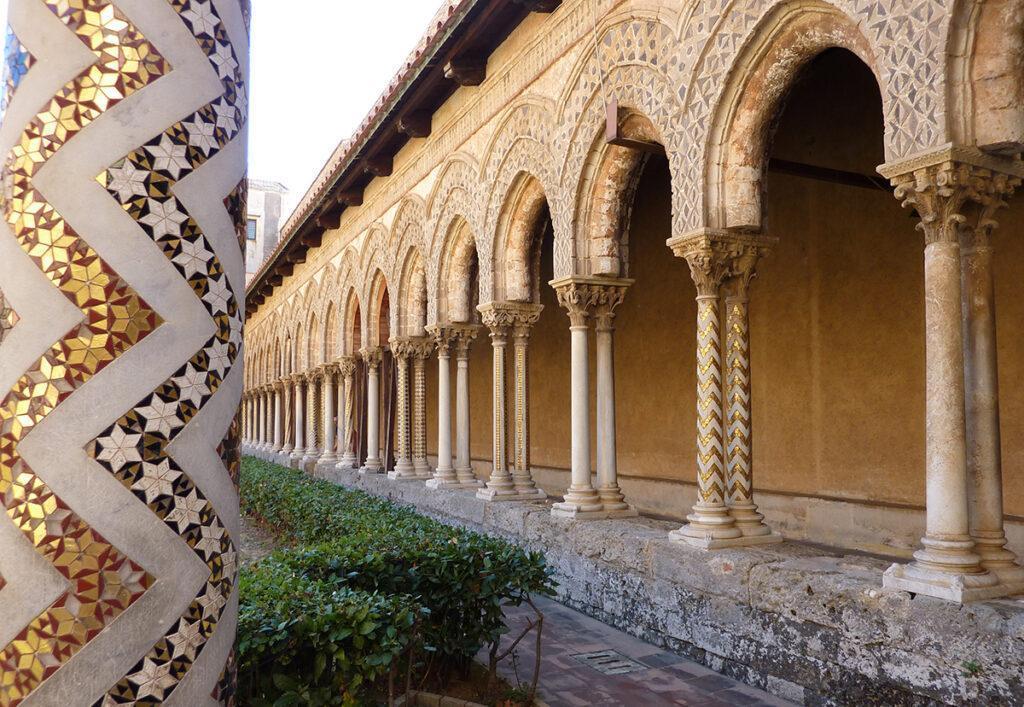

Regarding the vindication of their history, although being prolific in both cases (Andalusia and Sicily), their references are distinct. While the glorious past of Al-Andalus, overshadowed as could not be otherwise by the former and later history of the South of the Iberian Peninsula, in Sicily the astonishing presence of Hellenic culture has also achieved in obscuring, simply by contrast, the later expressions of the cultures that settled in the land of Etna. It is obvious that the ensembles of Agrigento, Selinunte, Segesta, Syracuse, Taormina, Erice, Gela, Heraclea Minoa, Himera, Megara Hyblaea, Soluntum and Tindari, with their grand temples, mostly in the Doric style, as well as their beautiful theatres, are considered the most grandiose of Antiquity, superior in many cases, mainly due to their excellent state of conservation, to those in the Greek metropolis. Yet, this should not consign to oblivion those elements that contributed to shaping the island’s history. For instance, it is hardly known that a Phoenician presence in the island, a century before the Greeks (9th and 8thcenturies BC), has left excellent archaeological sites, like the one in Motya. The Sicilian Middle Ages is another of the most brilliant and unique periods of its history. The Muslim conquest of Yazirat Siqiliya took place in the year 827. An emirate was soon consolidated with Palermo as its capital. Its conquest later by Normans opens an era of cultural mixing of an enormous importance. In fact, we can say that only in the island society was possible a cultural exchange between Christianity and Islam that is comparable to what is called “Mudéjar” in Spain. The so-called “Sicilian-Norman art” is the result of that combination, in which Muslim features kept on acting as cultural references. The palatine chapel of Palermo, as the castle of Zisa (Qasar al-Aziza) or the Monreale Monastery, represent a particular art created by Muslim builders on behalf Christian rulers—a sort of “Mudéjar” of Sicily.

Apart from this syncretism, we do not know about any strictly Muslim art on the island, which was 200 years under the rule of the emirate. In fact, we can scarcely trace some elements that came from the art of Ifriqiya after the later expressions in the 12th century.

The formation of a new Sicilian society after the Norman Conquest entailed that a Muslim minority under a Christian power had an effective and relevant social presence. Both societies were permanently driven into an ambiguous situation, where episodes of harmony were followed by others of great tension, in a balance that was sometimes broken and other times kept. These two social experiences are of the most interest, for the relationships between Islam and Christianity become more than general statements.

However, as we have pointed before, the experiences lived in the Iberian Peninsula and in Sicily did not coincide, for the situation of both conquests were diametrically opposed: In Iberia, the so-call “Reconquest” must be understood as a mise-en-scene of local powers from the northern area struggling to combat Islamic Al-Andalus, while in the island of southern Italy, forces beyond local powers were operative. In fact, the Norman conquest of Sicily, and of Palermo in particular, in the year 1072, can be only conceived as personal achievement of the Altavilla brothers and the knights who accompanied them, in that they had to make pacts with the local Muslim powers to create a new social order. There is no doubt that Normans, at the beginning, were an external minority in the face of majority communities, like Muslims, Hebrews, and Greek-Byzantines, which were all settled in the island since ancient times.

The history of Sicily shares, as does the history of all peoples, episodes of cohabitation and of tension.

Greek-Byzantines remained in the island under Muslim rule, and at the time of the Conquest many abandoned it, which shows that under any power except that of Christians they could totally uphold their freedoms and their different activities, most of which were commercial. However, those who stayed after the conquest came to occupy important places in the new chancellery. For their part, Jews, as time passed, played an important role as merchants, an even more so after the 9th and 10th centuries, when most of the Muslim presence in the island had ended. Finally, the legal and social status of Muslims in the cities and the Sicilian countryside was considered quite unequal in favour of city-dwellers: while in most of the urban centres personal freedom was ensured, the conservation of their goods, the free exercise of their religion ─of course under the obligation to pay the taxes due─ the most influential aristocratic groups preserved their social relevance. On the other hand, in the countryside, where the conquest was most violent, Muslims were forced into servitude in several ways, as shown in different registers, mostly ecclesiastical, of peasant farmers who were dependant on their lords. However, together with this class of dominated peasants, there was a group of free Muslims, in some cases prominent ones who held military functions serving Norman kings.

Baroque, the art that spread the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, shares prominence in both the south of the Iberian Peninsula and Sicily.

Church of Saint John of the Hermits in Palermo.

According to available sources, in 12th-century Sicilian society exchanges of all kinds were made, although the fact remains that the establishment of “morerías”(Moorish quarters), which did not exist at the beginning of the conquest, being described by the native from Al-Andalus Ibn Jubayr in the year 1185, meant also the diminished importance of Muslims, until they disappeared altogether during the middle of the 13th century, after the last revolts in the year 1243. Paradox, as we have pointed out, meets the eye: the end of the Muslim minority is validated by king Frederick II, himself so keen on Moorish culture, as shown in the cultural expressions he sponsored.

The island is divided into nine provinces, whose capitals are also their only cities. While the interior is mostly agricultural, like Enna, Caltanissetta and Ragusa, on the coast we find cities with healthier economies: Trapani, Agrigento and Syracuse. Finally, the three big cities are, along with the capital Palermo, Catania and Messina. Besides these administrative seats, Sicily holds urban landscapes of extreme beauty, like Taormina, the old Tauromenion. Palermo, the Greek Panomos and the Roman Panomus, is a big city which has undergone considerable growth over the last years, reaching one million inhabitants. The historic capital of Sicily summarizes in its monuments of the 12th century the splendour of medieval Sicily, where Latin, Greek and Roman influences are interwoven. In that century, the traveller from Al-Andalus Ibn Jubayr actually described Palermo as a prosperous city, calling it, significantly al-Madina (the City): “It is, in these islands, the mother of city life, meeting two beauties: wealth and splendour. It has the beauty desired for an inner state or the eyes, and to secure a fulfilled and exuberant life. Old, elegant, splendid and pleasant, it rises with a captivating aspect; it appears over all its squares and spaces like a garden. Its roads and broad streets catch the looks with rapture by its distinguished aspect, of an admirable nature, built in Cordoban style”. The rest of capitals are the typical southern cities, with plenty of Baroque monuments, but rendered ugly due to the urban disorder of recent years. This is Sicily, a land of contradictions where a relentless mountain overlooks placid agricultural fields; a country that treasures a historic patrimony like no other, and in which tourism and speculation are nevertheless ruining very beautiful sites. It is a corner of the world in the heart of the Mediterranean Sea which has a proverbial hospitality and clearly illustrates cultural mix.

By Virgilio Martínez Enamorado

Arabist and archaeologist, he holds a doctoral degree in Medieval History.