When The Alhambra was in ruins

The process of restoring the monument up to the fire of 1890

The Alhambra has inspired artists, historians, archaeologists and even visitors whose only purpose has been to enjoy the pleasure of gazing at its palaces or exploring its streets and gardens. For centuries, an idea remains fixed in the mind of those who look at the Alhambra, and this is the contradiction of a concept of its ephemeral qualities and its strength.

Romantic painters offered both versions. They either sought out the ruinous look of Moorish Granada or displayed the palaces in an idealized way for artistic reasons more aesthetic than real.

Even so, there is something we agree with ever since then. We are so impressed by its magnificence that we are unable to discover even the smallest detail of ruin or deterioration. It was an unintentional strategy that allowed these stones to be saved from the lack of commitment that the monument suffered for years, for not even the government was able to grasp the necessity of a definitive restoration.

The Alhambra was in serious danger of death. It is necessary to remember that the Alhambra was at risk of dismembering, of disappearing and, to some extent, we contributed to it. Taking this into account, we will perhaps be more respectful next time we visit it.

The Alhambra has known many disrespectful guests. The first and best known were the French. After invading Spain, they kept up their devastating practices. In the case of the Alhambra, rather than plundering it, they mistreated it. The Court of Myrtles became a projectiles depot; in the Court of the Lions, the flooring was pulled up to plant a garden of roses, jasmine and myrtle instead, in the French style so in vogue at the time. The rich coffered ceilings, doors and vestibule of the Tower of the Captive went missing. Plundering continued until 1812, when, as luck would have it, the Alhambra was evacuated. Yet French soldiers left mines all over as a reminder, and eight towers of the ensemble were blown up. Thanks to the already famous cabo de inválidos (sergeant of disabled) José García, who is remembered in a memorial plaque at the Square of Cisterns, this barbaric act was brought to a stop, yet many of the towers never recovered their original features. The Tower of the Seven Floors, for instance, an imposing gateway, would remain mutilated evermore.

Detail of the Tower of the Seven Floors, by Girault de Prangey.

The Justice Tower can be seen behind it. In the famous Tower of the Seven Floors, a very popular tavern was opened there years later, as well as a hotel, that remained open until 1936.

Once the Alhambra was abandoned, emptied of its foreign dwellers, it remained at the expense of other vandals, the locals, that is to say, the Spanish. The Court of Myrtles was at the mercy of mercenaries and drunkards, who set their stalls around the central pond to enjoy its water during hot days. Other ponds were used as public washing places.

The towers of the enclosure began to be inhabited, some by craftsmen and others by people of other social condition. Gypsies took over the Moorish houses and made bonfires indoors. And, of course, we should not forget the wide variety of beggars and disabled people who took advantage of the empty spaces in the Alhambra to accommodate themselves, as they were places suitably far from the medina and protected from exposure to the elements.

One fine day in 1829, the American writer Washington Irving arrived at the Alhambra and turned it into the main character of his tales. “…His writings on the state of the Alhambra caused such an embarrassment that the government finally decided to pay attention to the ensemble”, says José Álvarez Lopera in his famous article, maybe the best ever written on the restoration process of the Alhambra, –“La Alhambra entre la conservación y la restauración (1905-1915)”-. Irving’s appeal regarding the ruinous state of the building, and later the success that his tales enjoyed abroad, prompted an unexpected interest, as people in Spain began to question the value of the ruins that had for so long been so familiar to Spanish people that they did not engender interest. However, Irving’s tales brought a great variety of foreigners who visited the Alhambra, among them renowned artists and writers, such as Théophile Gautier, Richard Ford, Alexandre Dumas and Hans Christian Andersen.

Washington Irving wrote: “The Alhambra is amidst a fast and parallel state of transition. When a tower starts to collapse, a ragged family takes ownership of it, occupying, in the company of bats and owls, its golden halls, hanging their rags, in a paragon of poverty, out their windows and viewpoints.”

Irving not only described it; he stirred a dormant feeling. To the 19th century mind, considering the new implications of the irrational in matters such as archaeology, he understood that the deterioration of the Alhambra was imminent and that action was called for. In its rooms, he discovered that others before him had arrived at the site and had decided to take part in its maltreatment, imposing their self-conceit upon artistic preservation. In this way, he discovered on the ephemeral walls of the Alhambra the signatures of Chateaubriand, Byron or Victor Hugo. Irving, accompanied at that time by his faithful friend, the Russian diplomat prince Dolgorouky, designed the “Alhambra Album” or “Signature Book” to “ensure a long life to the travellers’ memories, and jointly preserve the building from calumnious reports”, as the prince made clear.

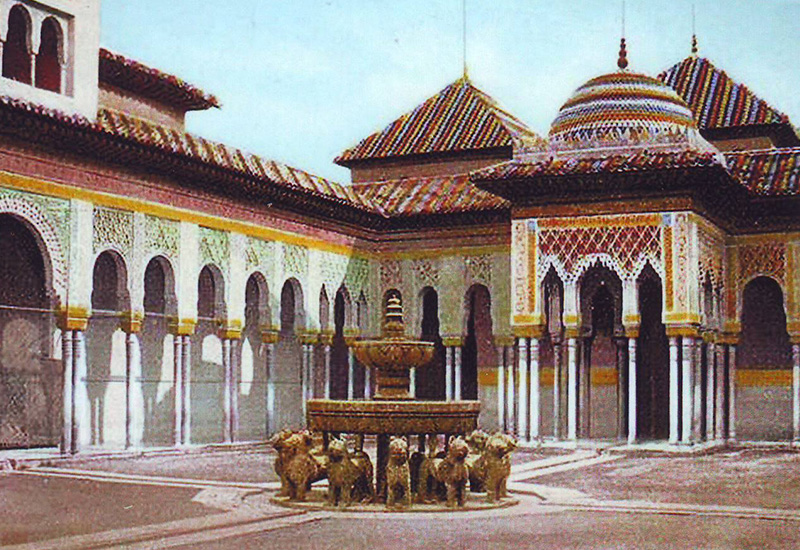

Torre de las Damas pintada por Frederick Lewis a principios de 1834.

Archivo del Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife.

The Tower of the Ladies before its restoration at the beginning of the 20th century.

Author: Torres Molina. Archivo del Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife.

Travellers from different parts of the world, and mainly Europeans, eager to experience exotic voyages but not wanting to risk the dangers of the Orient, discovered in Spain the ideal setting in which to search for adventures. Artists from around the world found a vein in Granada, and particularly in the Alhambra, a field of inspiration: for the painters, there was nothing in the city that was not worth painting, given its beauty and artistic value; writers experienced the same, for while some felt regret at the deterioration of the Alhambra, other praised it and admired its beautiful ruins, and there were those who imagined it when it was inhabited by sultans and concubines.

Girault de Prangey, quien dibujaría uno de los primeros libros de la Alhambra en 1832 diría:Girault de Prangey, who illustrated one of the first books on the Alhambra in 1832 wrote: “Of all its glories, of all its wonders, the Alhambra keeps only what neither time nor men have been able to take out from it, and they are its sky and the scented mists of its mountains; but its palaces of gold and azure, its mosques of radiant domes, its minarets, and even its gardens, everything has disappeared. Two or three convents, some miserable families settled among its ruins, old disabled people who starve to death, these are now the heirs to the kings”.

In that same year, David Roberts and John Frederick Lewis produced the best pictorial album on the whole Alhambra. Its plates continue to be distributed in souvenir shops, and whether they are real depictions or not, they will remain in our memory as the symbol that what the Alhambra was and will never be again.

David Roberts used his fantastical archaeology, adding things where it was clear they were not, changing churches and accentuating the ruinous state of buildings and walls, as it suited him, always aimed at getting a more romantic and visual painting. He was passionate about landscapes, and he disseminated an Alhambra essentially cosmic and universal. Lewis was more careful. He got into the palace, defined its muqarnas and incorporated figures, giving his work a more human aspect. Both contributed to make a global image of the building that has been very useful to those who, in the future, decided to restore it and then preserve it.

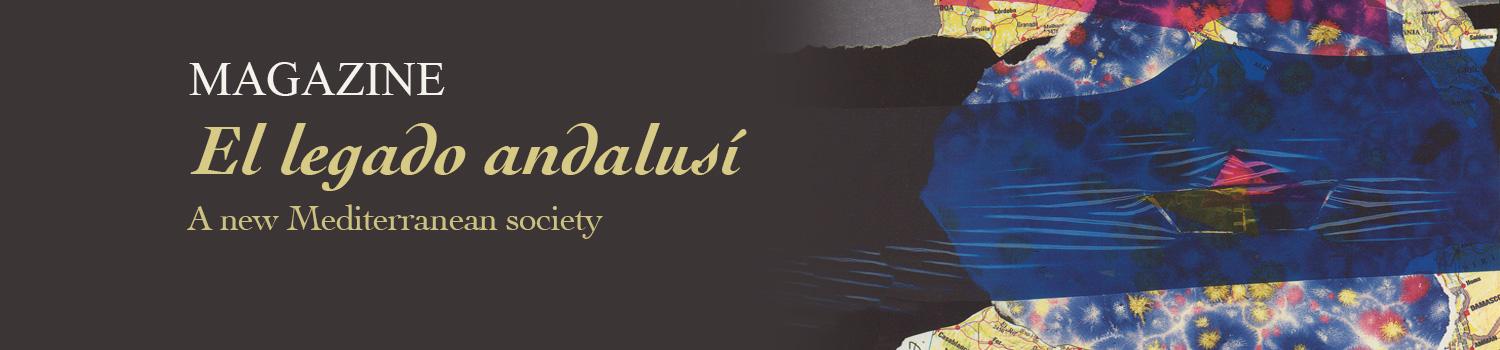

Postcard of the Alhambra wherein the glass tiles and the oriental-style .

dome can be seen, as well as the addition of a second fountain.

Yet it is hispanist Richard Ford, who is to be thanked for his detailed study of the Spanish people of the time. He observed the Spanish customs from a tolerant point of view, and hence he published essential books like Gatherings from Spain and A Handbook for Travellers in Spain. However, being as he was a standard-bearer and a hard critic of the idleness of the government, and loving our land as he loved it, he had no reservations about leaving his handprint in the edge the fountain basin of the Court of the Lions, a graffiti that was found in 2007 when the fountain was disassembled to be restored. Perhaps he only wanted to leave a written record during his stay at the Alhambra because, despite being a “Hispanophile”, he wanted to be noticed, like the good Englishman he was.

The Court of the Lions was the most reviled part of the Alhambra. Théophile Gautier, author of The Novel of the Mummy, slept on the floor of the courtyard several nights while his wine was cooling down in the famous fountain. Given that the architecture of this courtyard was more delicate, it proved a great success among visitors, although its scant dimensions were disappointing, as they had been manipulated by the exaggerations of the Romantic artists.

Years later, almost by the half of the century, the intrepid traveller Josephine de Brinkmann wrote: “What an adorable view! But, how saddens the spirit to see the heaps of ruins all around!” … “This must make the heart shrink for those who love arts and history after seeing the state of abandonment in which this has fallen, to see the wonderful walls and its embroideries sinking everywhere”.

In 1847, Rafael Contreras was appointed as decoration restorer. This fact, which should have marked a before and an after in the Alhambra, did not achieve the expected results, however. Many are the names that from those times should have been associated to the monument and be considered as the guardians of the Alhambra. Manuel Gómez-Moreno González, who always kept an eagle eye on Contreras’ works, said about him that since he was appointed curator, “a bigger respect for the old can be observed, but it is regrettable the ease he gets on with sometimes.”

In the year 1835, a second basin was already added to the Fountain of the Lions, with no foundation. This capricious detail merely confirmed the Alhambra’s vulnerability. Once again it all was in other hands, not in those of looters but certainly in arbitrary ones. However, a very well-known episode in Granada of that time was the confrontation between two very different attitudes: those who wished to restore the monument and recover its original state, and those who only wanted to preserve it and dealing with only its most basic maintenance.

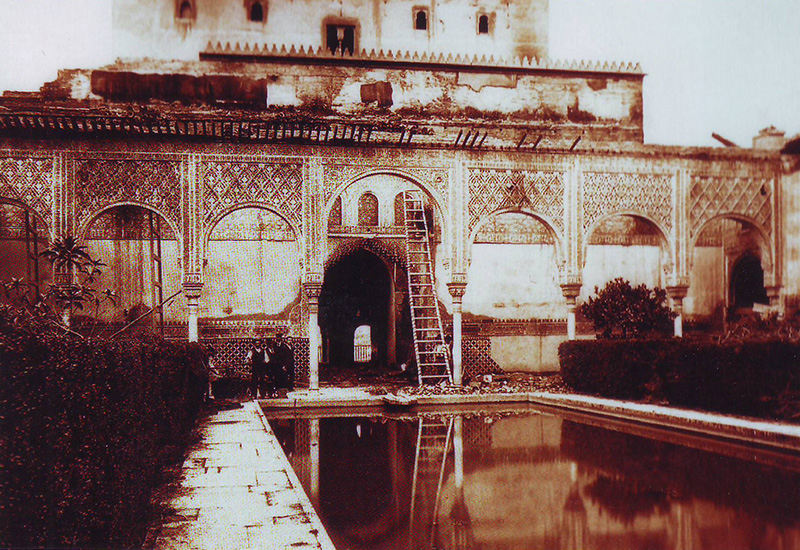

North gallery in the Court of Myrtles after the 1890 fire.

Photo attributed to A. Barrencheguren. ©Archivo de la Alhambra y Generalife. Catalogue of the exhibition “Imágenes en el tiempo, un siglo de fotografía en la Alhambra, 1840-1940.” 1840-1940.

Rafael Contreras came from a family deeply rooted in Granada. He had power, but he was not an architect. He had a great virtuosity, especially for miniatures, as those in the Hall of the Two Sisters, which was very popular at the time. He decided to transform the Alhambra in a palace of “One Thousand and One Nights.” The little domes and glassed gables in the Courts of the Lions and Comares belong to this period. They were very personal interpretations that remained in the monument until the intervention of the prominent architect and archaeologist Leopoldo Torres Balbás almost a century later.

The same happened with the tilings, which took colourful nuances, very distinguished and picturesque, although without any artistic basis. “All that introduced –leaving aside inaccuracy or falsifications, with a complete disregard to time and history– the factor of discordance between what was restored and what was not, which was clearly against the global unity and the significance of the monument”. (Álvarez Lopera).

Photographers witnessed this process first hand. Pictures taken in 1855 show the Court of the Lions under braced roofs. Three years later, the oriental cupola is portrayed, and the crossbeams and pillars holding it could not hide its poor state of conservation. We have seen some pictures in recent exhibitions in which we are amazed to see that even at those times, there were people still living in the palace, and it was clearly seen how windows were used for drying clothes. The Machuca Tower and its courtyard causes overwhelming sadness, with its coffered ceilings broken, weeds growing all over, in a space that in other times was a royally quiescent place.

However, we are wrong when we thought that the ruin of the Alhambra was imminent, for the horror of every monument was still to come: fire.

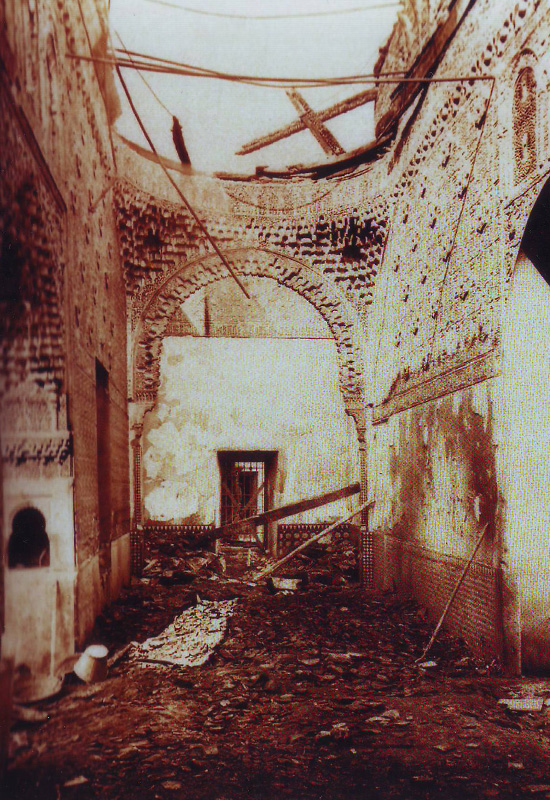

“The palace of the Nasrid monarchs was burning, voracious flames menaced to destroy the richest jewel we inherited from Arab art…”, reported the journal on the event that took place on September 15, 1890,La ilustración española y americana.

The Alhambra had been already declared national monument, and its situation started to generate many contrary opinions. Architects, archaeologists, curators, historians… each and every one thought they possessed the truth regarding the decisions taken towards the monument, but the task was not easy, for as they were focused on restoring, the preservation of the damaged parts was not considered an important need.

It cannot be proven that the fire that took place on September 15 was intentionally started, but it was believed to be so, and it was said so without doubt. Francisco de Paula Valladar stated with absolute frankness in his bookThe burning of the Alhambra that“the arsonist, in case there is one, as it would be expected to be one, had to plan very well his work: the East wing of the Court of the Pond is today the junction of everything remarkable that holds the alcazar”. And it was there where the flames acted most violently. It was not the first burning in the palace though: the same area had been already damaged centuries before. The Hall of the Boat was cruelly attacked by fire; its ceiling was lost entirely. It was a unique model of its kind, as Paula y Valladar stated. Fire also swept over the Comares Palace’s hall as well as the hedges that surrounded the pond, which also affected the Court of the Lions. The restoration that in previous years was undertaken in this area by Contreras was gone, together with the remains of what was authentically Nasrid. It could have been the right moment to set the most elementary priority: to focus on a more logical reality. Yet, the oriental fantasy prevailed again, and the Palace of Comares was crowned with domes, over the glassed tiles. Money lasted only two more years, and in August 1892 works stopped due to the lack of economic resources.

First pictures of the Room of the Boat after the fire of 1890.

This hall remained in this state until its restoration was finished in 1964.

Author: Torres Molina. Casa de los Tiros Museum, Granada.

The Alhambra and its current reality

It is quite hard to imagine what a monument was like in its original state when only ruins have been left to be restored. It is one of the major challenges that architects and archaeologists have to face. After all, the confrontation that took place between curators and architects seems not to have an end. Further reflection is needed to manage such an important monument, and the priority that tourism must have. Tourists are petty plunderers: they touch, pull off, and tread, of course unintentionally, but this confirms the idea of the small vandal we all have within. We must give a vote of confidence to tourism, with whom the Alhambra has a symbolic relationship, while we trust in Irving’s words:

“By observing the marvellous tracery of the peristyles, and the apparent fragility of its walls’ openwork, it is difficult to believe that this had survived the passing of time, earthquakes, wars, violent as well as peaceful and though no less harmful, the enthusiastic traveller’s burglary, which is enough to justify that everything here is protected by a magical spell”.

By Carolina Molina. Journalist and author of historical novel

To know more:

-Casas y Palacios nazaríes (siglos XIII-XV). Antonio Orihuela Uzal. Ed. Lunwerg /El legado andalusí. 1996.

– “La Alhambra entre la conservación y la restauración (1905-1915).” Álvarez Lopera, José. Cuadernos de Arte de la Universidad de Granada. Granada, 1977.

-El incendio de la Alhambra. Francisco de Paula Valladar. 1890.