Walks through Córdoba

Years later, the Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I, who had fled from Damascus, where his family had succumbed at the hands of the rival Abbasid dynasty, established an independent state in al-Andalus, that meant the beginning of the period dominated by the Cordovan Umayyads. It was Abd al-Rahman III who, on his rising to power in 912, began the transformation of a divided territory into a centralized state and proclaimed himself as independent caliph. Córdoba became the most splendid city in the civilized world: it had more than a thousand mosques, more than eight hundred hammams (public baths), an innovative urbanization system, a varied and flourishing trade, illumination along the main streets (in this aspect it was 700 years ahead of London or Paris), got built the largest and most beautiful mosque of the time, or a magnificent entire palatine city, Madinat al-Zahra, in the nearby mountains. The subsequent caliphs, Hisham II and al-Mansur, consolidated this splendour, and the greatest library that existed in Europe during the Middle Ages was created there. Subsequent decline precipitated the advance of Castilian power despite the interventions of the Almoravids and the Almohads.

Ferdinand III entered Cordoba in 1236. During the war of Granada, the Catholic Monarchs established their headquarters in the city, in an Alcazar (fortress) where Isabella received Columbus to listen to a proposal that would change the course of history.

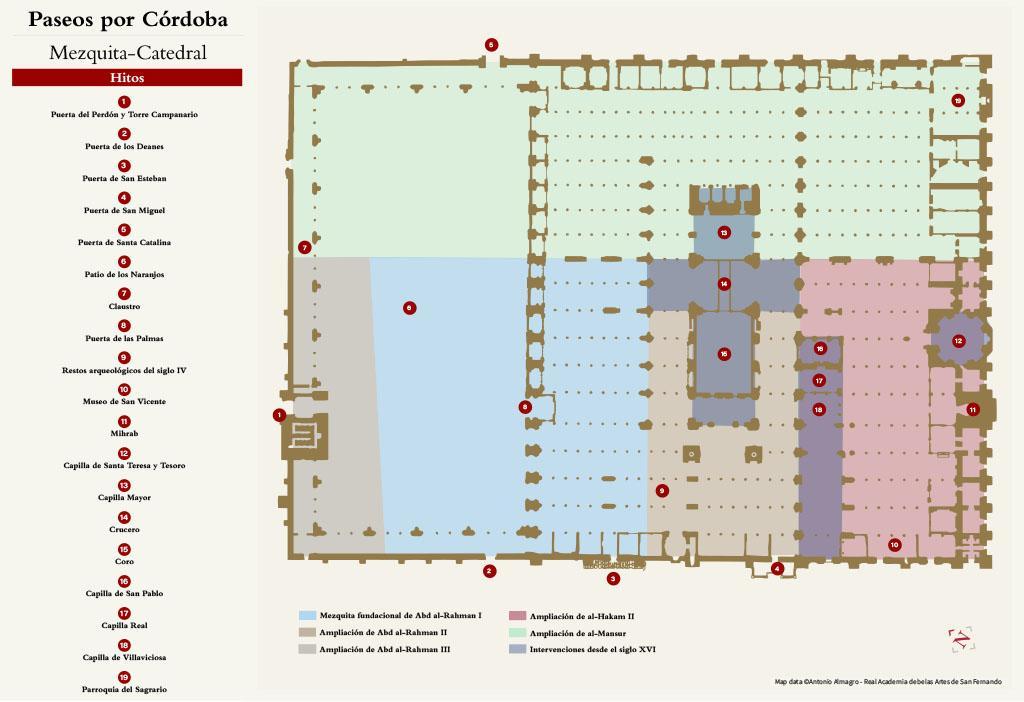

1. The Mosque

Download Map of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba

Our walk through Cordoba starts by visiting the Mosque, one of the most relevant artistic constructions of all times, a World Heritage Site and one of the most important monuments in the Islamic West. The fame of the Cordovan Mosque spread rapidly after its construction. In the 12th century, the geographer from Ceuta al-ldrisi wrote “it had no equal among the mosques of the Muslims, neither for its size nor for its beauty”.

The construction of the mosque lasted barely one year and was started by Abd al-Rahman I in 785. Subsequent emirs and caliphs continued to expand it all over the next two centuries: Stylistically, it reflects the evolution of Emirate and Caliphate art, as well as Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles as a Christian cathedral after the Conquest and its consecration in 1236. Stylistically, it reflects the evolution of Emirate and Caliphate art, as well as Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles as a Christian cathedral after the Conquest and its consecration in 1236.

It consists of nineteen naves perpendicular to the qiblawall, where Roman and Byzantine influences are visible regarding the layout, marble and mosaics. These aisles shape a panorama of superimposed arches at two levels, the lower one built with horseshoe arches and the upper with rounded arches. The ochre stone and red brick create the world-famous two-colour pattern that, covered by a wooden ceiling and in silent majesty, prepares the visitor’s spirit before entering the mihrab, commissioned by caliph al-Hakam II to artists from Damascus and Byzantium, but not before admiring the maqsura or space reserved for the caliph.

-

Archs. Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba

-

Royal Chapel. Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba

-

Maqsura of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba

The Patio de los Naranjos (Orange Tree Courtyard), to the north, is flanked by galleries with triple semi-circular arcades on three sides and blind horseshoe arches on the fourth, where the Puerta de las Palmas (Gate of the Palms), renovated during the Renaissance period, opens up. In the centre of the courtyard five fountains are to be found -three Mudejar and two Baroque-, as well as the remains of the ablutions basin. Inside the bell tower, built in Renaissance style at the lower section and Baroque at the upper one, the old minaret of Hisham I is preserved.

On the outside, the building shows medium-height walls reinforced with regular-section buttresses. On the mural walls the entrances to the church open up, most of which were remodelled in later periods and some of them have undergone significant restoration. The main one, the Puerta del Perdón (Gate of Mercy), on the northern façade, shows various harmonised styles. On the western wall is one of the oldest, that of San Esteban, dating from the times of Abd al-Rahman I; Deanes, Postigo de la Leche and Puerta de San Miguel gates were all renovated in the 16th century. On their part, the Gates of al-Hakam II, display great decorative profusion and further complexity in their composition.

In the central area of the naves, the Christian kings ordered the Great Chapel and the Royal Chapel to be built. In 1523, work began on the Cathedral inserted in the forest of columns at the request of the Chapter of the Cathedral and with the support of Emperor Charles V. The work was begun by Hernán Ruiz the Elder, who was succeeded by his son Hernán Ruiz the Younger in 1545. The cathedral presents a Latin cross plan with side chapels covered by ribbed vaults in the main chapel, half-barrel vaults in the choir and elliptical vaults in the transept.

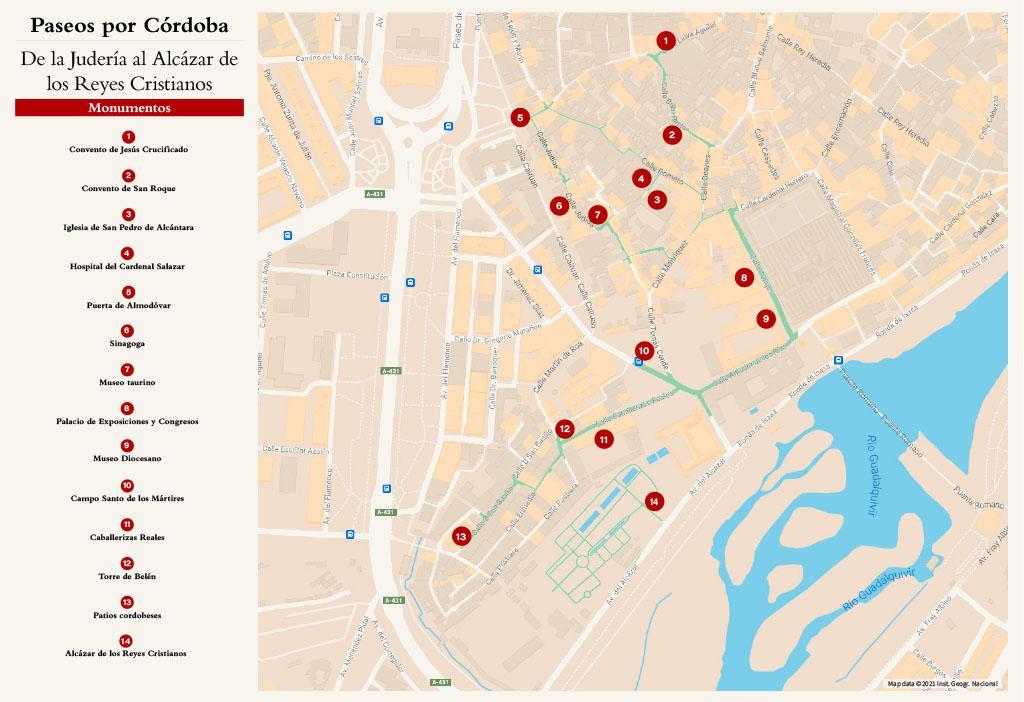

2. From the Judería (Jewish quarter) to the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos

Our walk begins in the Jewish Quarter, a labyrinth of narrow, white streets adjoining the city walls whose origins date back to Roman Corduba and where the different Visigothic, Muslim, Jewish and Christian cultures have lived and even coexisted. All of them have left their architectural, sculptural, pictorial and customary mark over the centuries, although its configuration and greatest splendour corresponds to the period of al-Andalus.

Our route proposed begins at the Church of the Hospital of Jesús Crucificado, whose construction started in the 16th century, being the only well-preserved remains of the complex that would later become a Dominican convent. We will continue along Buen Pastor street to find the convent Church of San Roque, from the 17th century, and behind it, the Church of San Pedro de Alcántara, next to which is the Hospital del Cardenal Salazar, a great example of Andalusian Baroque that currently hosts the University of Philosophy and Literature; inside, the chapel of San Bartolomé, an ancient medieval chapel, shows great artistic and historical value.

At the end of Almanzor street, the only surviving example of the city’s monumental medieval gates is still to be seen: the 14th-century Puerta de los Judíos (Gate of the Jews) or Almodóvar Gate, built on top of a 10th-century gate, that was called Puerta del Nogal (Walnut tree gate) at that time.

We continue our walk through the Jewish Quarter with a visit to the Synagogue, the only remaining example of those temples that once stood in the Jewish quarter of Cordoba. Dating from 1315, after the expulsion of the Jews it was reconverted into a hospital for hydrophobia patients, before passing in the 16th century into the hands of the shoemakers’ guild. It has a rectangular floor plan, and of all the ornamental work that covered its walls originally, only the plasterwork on the upper part has been preserved. An inscription therein bears the name of the synagogue`s founder, Yishaq Moheb.

In the Square of Maimonides we can visit the Bullfighting Museum, located in part of the former manor house of the Bulas family, and bordering the Mosque along Torrijos street, the Diocesan Museum and the current Exhibition and Congress Center, separated from each other by the oldest stretch of al-Andalus walls in Cordoba. It belonged to the northern wall of the Umayyad sovereigns, visible from a side courtyard of the second building, the former Hospital of San Sebastián, built under the direction of Hernán Ruiz I between 1513 and 1516, bearing a two-storey Mudejar courtyard. The Diocesan Museum, for its part, is located on the site of the old Visigoth and Muslim alcázares (fortresses), and its main architectural elements are original from the 17th century.

We continue through Campo de los Mártires, where we find the remains of the Arab baths, dating from the Caliphate period and belonging to the today disappeared Umayyad fortress. They were later reused in the 12th and 13th centuries by the Almoravids and the Almohads.

On our way to the Patios of the Alcázar Viejo (Old Fortress), we find the Caballerizas Reales, (Royal Stables), founded by order of Philip II, and rebuilt after the fire that destroyed them in the times of Charles III; the walls of the enclosure known as Castillo de la Judería (Castle of the Jewish quarter), from the 14th century, and the Tower of Belén, the only surviving gate of the enclosure. This work dates back to the Christian Conquest, although has similarities with Almohad constructions.

Now we head towards the neighbourhood of San Basilio, or the Alcázar Viejo (Old Fortress), the heart of the Patios of Córdoba, declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2012. The courtyards of these houses are one of the main tourist attractions of the city. They are noted for their beauty, the good care of plants and flowers, and the friendliness and willingness of their inhabitants to share their treasures with visitors. The layout of the neighbourhood used to be in a straight line, with three main axes, Postrera, Enmedio and San Basilio streets, although the houses still retain Arab reminiscences, such as the arrangement of the rooms around the courtyard.

We retrace our steps back to the Campo Santo de los Mártires to finish with a visit to the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos. (Fortress of the Christian Monarchs). This fortress-palace stands on what was part of the site of the old al-Andalus citadel, and the first constructions date from the times of Alphonso X the Wise, although it was Alphonso XI, who built a large part of the current construction in 1328. It was the residence of the Catholic Monarchs during the war of Granada and, from the 15th century onwards, the seat of the Inquisition Tribunal. It treasures a valuable collection of Roman mosaics (2nd and 3rd centuries AD) with different figurative and geometric motifs. The Royal Baths are located beneath the Mosaic Hall. The Arab-inspired gardens are also outstanding, striving with palm trees, cypresses, orange and lemon trees that alternate with fountains and ponds.

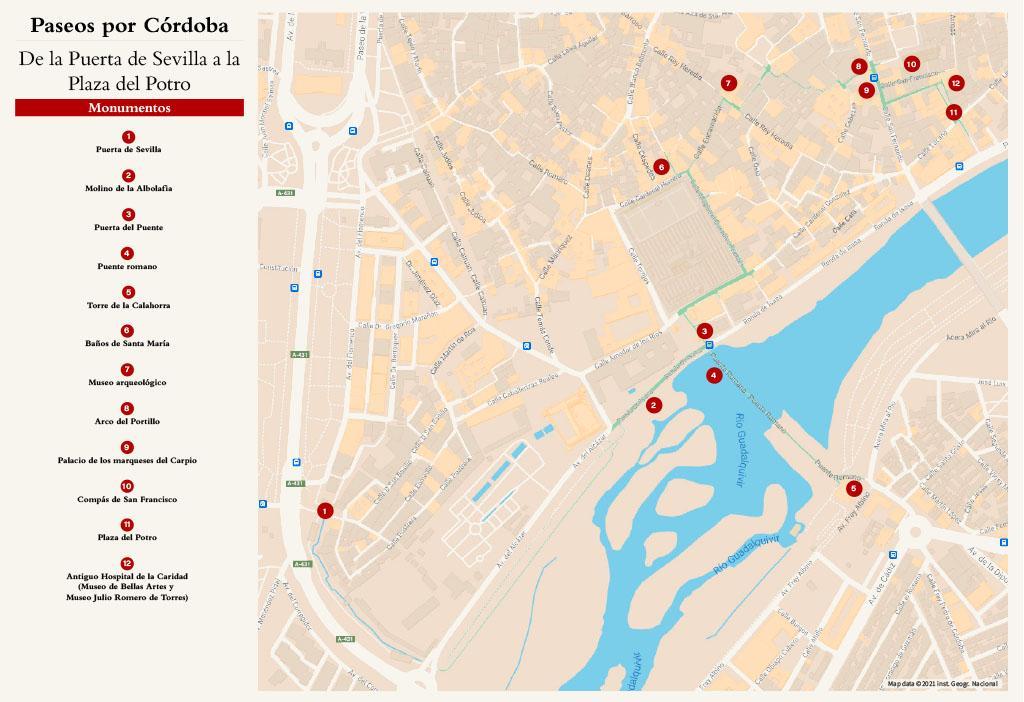

3. From Puerta de Sevilla to Plaza del Potro

Download street map Walk 3. From Puerta de Sevilla to Plaza del Potro

Next to the current Puerta de Sevilla (Gate of Seville), that contains the remains of a defensive complex dating from the 10th century, starts the western wall, which descends towards the river. It consists of a Christian work from the 14th and 15th centuries, with a barbican and a moat. Along the Avenue of the Alcázar, near the bridge, we can observe several Muslim mills located on the banks of the Guadalquivir river, in the vicinity of the bridge, whose function was to supply water for the irrigation of the gardens of the Alcázar and the Mosque. One of the most important of these is the Albolafia Water Mill, which has been present on the city`s coat of arms since the 14th century. Its waterwheel with earthenware buckets is a recent replica of the original one.

The Puerta del Puente (Gate of the Bridge), rebuilt in Renaissance style by Hernán Ruiz III during the reign of Phillip II, is located opposite the Roman Bridge. This bridge is a medieval work made up of sixteen arches, with rather little remains from its Roman past, although there are references to the times of Julius Caesar. The first reconstruction known was started in the year 720.

Crossing the bridge we get to the Calahorra Fortress, built by the Muslims as a coracha (stretch of wall for protective purposes) on the other side of the river. It was reformed in 1369 and its current construction is Christian. In the 18th century it served as a prison for the nobles of Cordoba.

Returning to the city, crossing the bridge back again, we go up the eastern side of the Mosque towards Velázquez Bosco street, close to the northern façade of the Mosque, where we find the Baths of Santa María, dating from the times of the Caliphate, which preserve the original structure of hot and cold rooms and a courtyard of columns, where the pool was originally located.

Along Encarnación street, our steps lead to the Archaeological Museum, the former palace of the Páez de Castillejo family. The oldest parts of the building date back to the 14th century. In 1496, the main construction work began with the participation of Hernán Ruiz and his son, Hernán Ruiz II, author of the façade, the staircase and the main courtyard. The museum houses collections belonging to prehistoric, Iberian, Roman and al-Andalus cultures.

Along San Fernando or Feria streets, the eastern fence of the Medina of Cordoba stretched out, which can be seen in small sections between the buildings. The Portillo Archis the surviving entrance to this wall, which was opened in the 14th century. Next to this Arch, the House de los Marquises of El Carpio, consisting of a medieval tower altered by later interventions. Opposite we can pay a visit to the Church of Compás de San Francisco, a former 13th-century convent, later transformed into a Baroque temple.

The Plaza del Potro, quoted by Cervantes in his works, houses the inn of the same name and the old Hospital de la Caridad, founded in the 15th century and now housing the Museum of Fine Arts and the Julio Romero de TorresMuseum. In the rooms of the former one there are works from the 16th and 17th centuries, a collection of Andalusian painting dating from the 19th and 20t centuries and an engravings exhibition. The latter one houses the works and personal memories of the Cordovan painter.

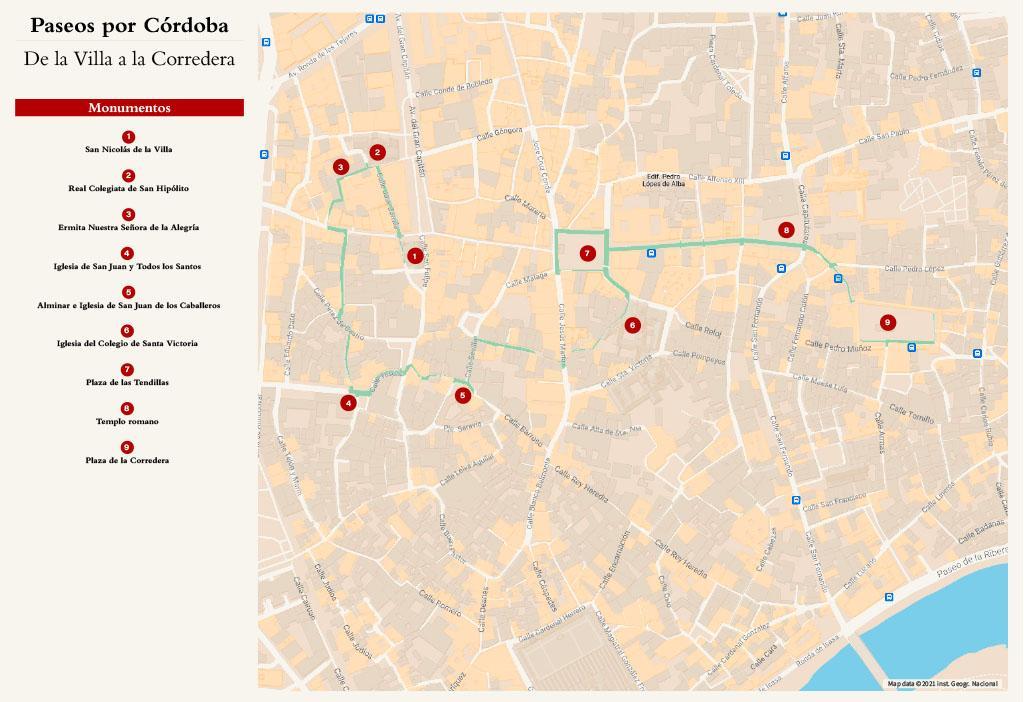

4. From La Villa quarter to La Corredera

Download street map Walk 4. From La Villa quarter to La Corredera

San Nicolás de la Villa is one of the oldest parish Churches in Cordoba, a prototype representing the period of the Ferdinand conquest, from 1236 onwards. The original Mudejar structure can still be noticed, showing a graceful 15th-century tower whose base is the old Muslim minaret. The church has two doors, the oldest one on the southern side; the north door, which opens onto Gran Capitán promenade, was built by Hernán Ruiz II in 1555.

Other outstanding temples in La Villa Quarter are the Church of San Hipólito, founded by Alphonso XI in 1343 as a royal pantheon, but whose works were not completed until 1736; the Hermitage of Nuestra Señora de la Alegría, from the 18th century and the Church of San Juan y Todos los Santos, which belonged to the old convent of La Trinidad, founded in 1241.

The most representative example of a minaretthat has miraculously survived to the present day, stands at the confluence of Sevilla and Barroso streets, next to the Church of San Juan de los Caballeros. The minaret was probably erected between the 9th and 10th centuries and has been declared a historic-artistic monument.

On the other side of Ángel Saavedra street is the 18th-century Church of the College of Santa Victoria, whose façade shows a portico ornamented with a triangular pediment, an outstanding work in the city. In La Compañía square, the current Church of El Salvador is located in what was formerly the church of the Jesuit college of Santa Catalina, which was suppressed in 1767. Two steps away is Las Tendillas square, the hub of the city, an open space surrounded by buildings dating from the 1920s around the equestrian figure of El Gran Capitán (The Great Captain). From there, Claudio Marcelo Street leads to the remains of a Roman Templewhose dedication is unknown; it consists of eleven columns belonging to a building that may well date back to the end of the 1st century, in the Flavian period, or perhaps earlier. Tundidores street leads to the well-known La Corredera, Cordoba`s main square; it was built in an area that was used as a market in the late Middle Ages. It was constructed during the Baroque period, while its completion dates from 1687. The prison, granary and alhóndiga (grain exchange market) date from the end of the 16th century.

-

La Corredera square

-

Church of San Nicolás de la Villa

-

Church of San Juan y todos los Santos, former Convent of La Trinidad.

-

Church of the College of Santa Victoria

-

Las Tendillas square

-

Roman Temple

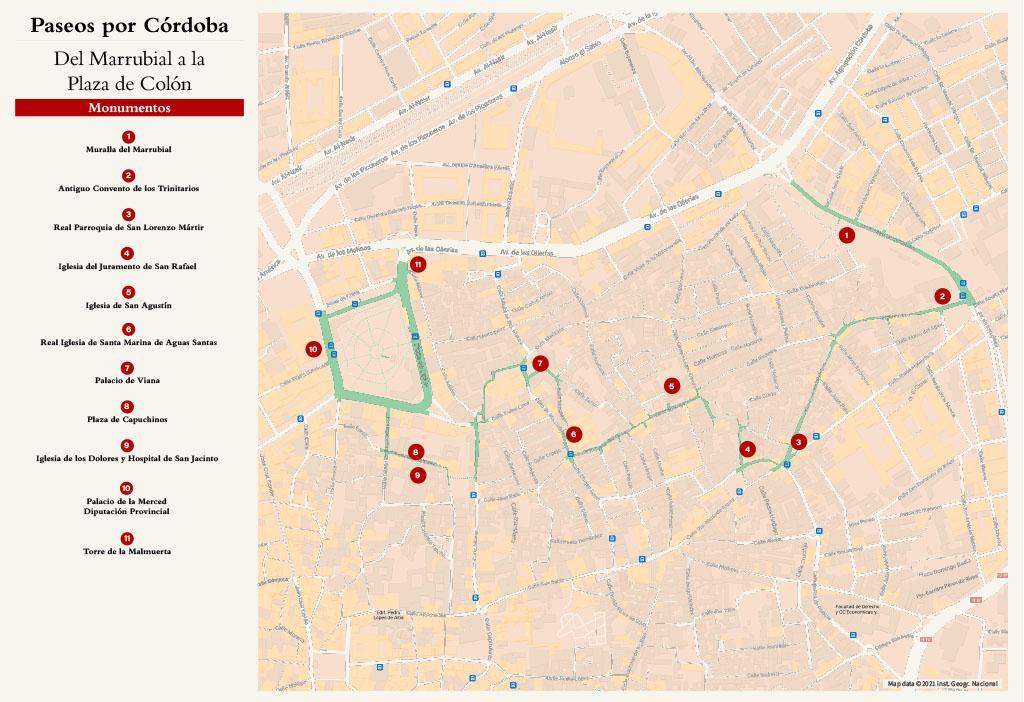

5. From Marrubial to Plaza de Colón

Download street map Walk 5. From Marrubial to Plaza de Colón

This walk begins on Ronda del Marrubial avenue, where a stretch of more than 400 m of wall crowned by fourteen towers is still preserved, with which the Almoravids enclosed the Ajerquía suburb, the area of urban expansion outside the walls in the Caliphate period. Continuing the wall southwards, we reach the former convent of the Trinitarians, where we find the imposing pre-baroque church of Nuestra Señora de Gracia, where we can contemplate a magnificent image of the Immaculate Conception by Pedro Roldán.

We continue along Frailes and Jesús del Calvario streets until we reach the Royal Parish Church of San Lorenzo Mártir; founded by Fernando III after his conquest of the city, its site was formerly occupied by a mosque. The first part of the tower belongs to the old minaret, which Hernán Ruiz II reformed in 1555. Nearby is the Church of El Juramento de San Rafael, which dates from the end of the 18th century.

We can wander through the alleys down to the Santa Marina neighbourhood, where the church of San Agustín stands, the remains of the Convent of the Augustinians, that moved to this site in 1328 and whose church was extensively reformed during the 16th and 17th centuries. Further on, Don Gome square is dominated by one of the most exceptional civil buildings in Cordoba, the Palace of the Marquises of Viana, whose origins date back to the 14th century; its main staircase, fourteen courtyards and numerous halls are outstanding. Nearby is the Church of Santa Marina, the heart of this parish congregation; it also belongs to the churches founded by Ferdinand III after the conquest. It combines late Romanesque and Gothic elements with Mudejar inspiration. In the square, a monument devoted to the bullfighter Manolete overlooks the façade of the church.

Passing through Puerta del Rincón (Corner Gate) we will arrive to Capuchinos square, in front of the 17th-century convent belonging to this order. It consists of a typical Cordovan corner, where the Cristo de los Faroles , the Church of Los Dolores -whose Virgin is one of the most venerated in Córdoba- and the Hospital of San Jacinto stand out.

Behind this place, Colón square spreads out, also called gardens of Campo de la Merced. It consists of a large green space flanked by the old 18th-century Convent of La Merced, current headquarters of the Provincial Council. It is a key example of Cordovan Baroque architecture, showing a splendid façade, cloister and imperial staircase. On the opposite corner of the square, there is a remnant of the defensive constructions, La Malmuerta tower, an octagonal defensive watchtower built on top of an earlier one in 1408.

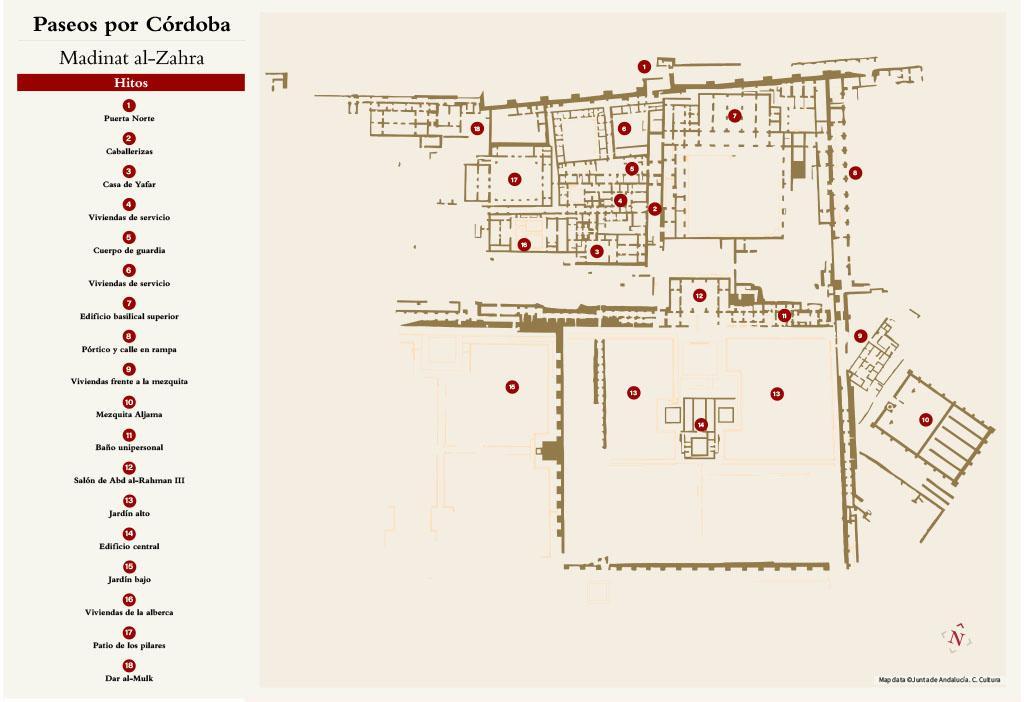

6. Madinat al-Zahra

Download Map of Madinat al-Zahra

The city of Madinat al-Zahrawas founded by Abd al-Rahman III eight kilometres away from Córdoba, at the foot of Sierra Morena mountain range. The chronicles of the time explain its foundation by reasons that are nowadays considered to be close to legend and attributed more to reasons of a political-ideological nature, such as the fact that the dignity of the caliph demanded the foundation of a city of his own in the style of Eastern caliphates.

Located on La Desposada mountain (Jabal al-Arus), we can easily follow the structure of a typical city of al-Andalus. The plan of the city is rectangular in shape and covers just over on hundred hectares, laid out in three superimposed steps that stretch from north to south.

Its construction began in 936 and lasted for 40 years, during the rule of its founder and his son, al-Hakam II, but the city had a short-lived existence, as it was stormed and burnt down by the Berbers in 1010. The ruins were abandoned and it was used as a quarry for extracting building materials during the following centuries, until in 1910, the first archaeological excavations revealed it was an archaeological site of extraordinary importance: Madinat al-Zahra, a World Heritage Site, the legendary city, the luxurious project conceived by the Umayyad dynasty and considered to be one of the summits of Islamic art and famous throughout the world for its architectural sumptuousness and decorative peculiarities.

The visit starts from the northern wall and the North Gate; a passageway leads to the upper terrace, which corresponds to the Alcazar (fortress). To the right of the visitor we find the chambers and courtyards of the caliph, which were built over the quarters of the guard corps, the so-called dwelling of La Alberca (pool) and the dwelling of Ja’far, a freed slave under the first caliph’s rule and later prime minister (Hayib) under al-Hakam. This is the sector where the best remains are preserved.

On the left there is a group of chambers related to the ministers’ house or public sector of the Alcazar (fortress), consisting of a reception hall, a square courtyard, landscaped with native species as well as the part that was once used for stables. From the courtyard, a ramp leaded to an eastern portico, the monumental entrance to the public area, in front of which military parades and official celebrations were held.

The middle terrace comprises the main part of the palace, including the great reception hall and its gardens. The Hall of Abd al-Rahman III or Rich Hall was built between 952 and 957 and consisted of a central portico with five horseshoe arches. The layout of the naves and side rooms reflects the delicate protocol of the ceremonies, embassies and receptions that were held there. The three central naves are divided by two rows of seven columns, and the interior walls of the Hall are richly decorated with marble and colours that at certain times of the day are able of restoring the delicate atmosphere they had at the time of its construction, and which aroused the admiration of all the visitors. Opposite, the Jardín Alto (Upper Garden) stretched out, enclosed by powerful walls that separate it from the area of the medina, the sector reserved for the plebeians, which is called Jardín Bajo(Lower Garden).

As we descend from the first terrace to the main section of the palace, we can admire the remains of the Great Mosque of the city, located on the third level. It was commissioned by Abd al-Rahman III in 941. According to some chroniclers, it took forty-eight days to be built. Only the foundations, the outline of its layout and the remains of an elevated passageway used by the caliph to enter the mosque remain today from such a hurried construction.

Partner companies